|

We have one word for many different things. We need more words. There are at least three categories of problems that seem relevant and worth distinguishing from each other. We currently only use one word, “problem”, for all three. I won’t create new words here, but below are the three categories various problems can be separated into.

The Socially Superficial Idealism. Abortion. Gay marriage. Transgendered people using bathrooms. Polygamy and polyamory. Adultery. Death penalty. Euthanasia. Suicide. Drugs. Religion. Racism. Sexism. The use of superficial here does not imply that these problems don’t have serious consequences. Instead, I simply mean that they would disappear tomorrow morning if everyone woke up with an agreement to just not participate in them as problems. Gay marriage is only a problem because some people believe it is a problem due to things like “souls” and “hell”. The same is true for the rest of the issues on the above list, with some nuances here and there. All of these issues stem primarily from philosophical idealism of the Platonic type. Religion, nationalism, Stalinism, Maoism, and any of a dozen others are forms of idealism. “If we can just get my version of the ideal actualized, the world will be perfect. Now let’s get rid of all the people that are ruining my ideal…” To the extent that a problem arises from some form of idealism or belief, it is a fabrication. Some of these items, like drugs can obviously be a problem when they contribute to people committing acts of violence and destruction. The same can be said about almost any sex act. Polyamory and adultery can be done violently or under threat of violence, but it’s the violence that is the problem. The Socially Substantial Violence. Education. Healthcare. Poverty. Inequality. Trade. Immigration. Climate change. Nuclear war. Artificial intelligence. Psychopathy. Terrorism. War. This category is contextualized by the issues being related to humans acting and interacting with each other, but could not be solved simply by stopping an action or disbelieving something. We could all wake up tomorrow and choose not to be anti-homosexual in our actions and speech. We couldn’t solve the issues related to the list of items in this category in the same way. They need genuine effort, systems, and experimentation plus time. In fact, it’s not even clear some of these issues have genuine solutions. The best we may be able to hope for in some cases, such as psychopathy, is containment. The Asocial Disease. Natural disasters. Aging. Dying. The items in this category are unique from the above two in that they don’t result from humans being social. Even if we decided to all play nice and work hard to create systems and institutions to deal with the substantial social problems above, we’d still be left with the asocial problems. We all get sick, old, and die. These are real problems that would plague us no matter the social utopia we built. Stop Being Distracted Yet we find ourselves most often discussing the first category of problems in the news and politics. The world as we know it could potentially end because of above items like A.I., climate change, or nuclear war. These are existential threats to humanity. They affect every single person. Moreover, they are hard problems to solve. None of the items in the socially superficial list will matter if solutions are not generated to the list of socially substantial problems. I can’t be any clearer, we need priorities. Spend your time, energy, and abilities on the most pressing issues and worry (or don’t) about the superficial ones later.

0 Comments

I’ve written much on the purpose of education. I’ve often discussed and reflected on it with Rebecca in particular.

Here are some of those past writings by Rebecca:

And by me:

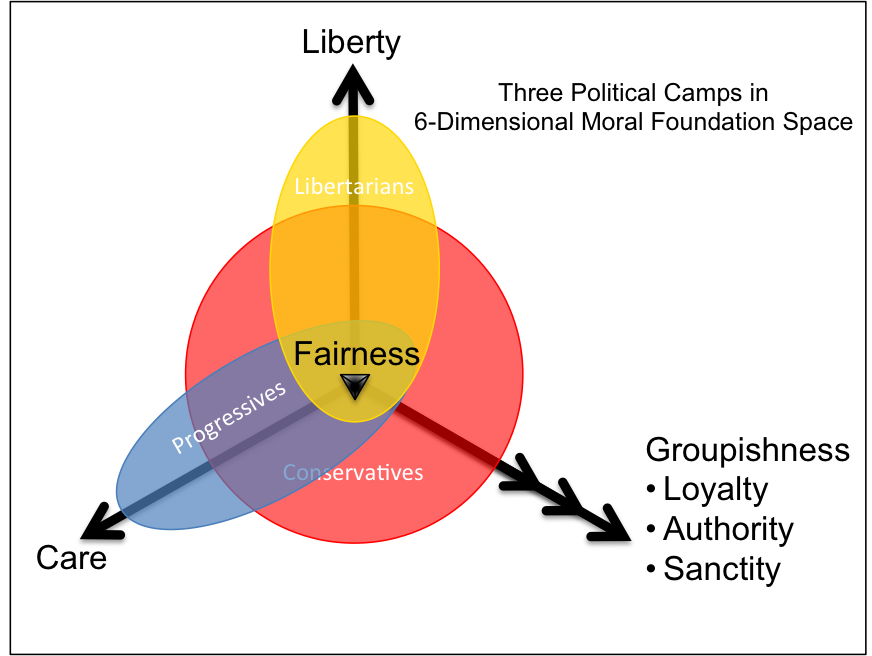

We’ve also literally written thousands of unpublished words on the topic, including over 10,000 words in an unfinished e-book that has been on the back burner for months, but spawned more thinking than any other single endeavor related to education I’ve been a part of, including a master’s degree and multiple education settings over the past thirteen years. So with all the abstract philosophical thought on the topic and much reviewing of the educational literature, here is a complete “perfect day” of secondary school as envisioned by us. The Daily Schedule 9:00 AM - Start of school. This isn’t super important, other than it isn’t super early. Many high school students naturally sleep in a bit later due to staying up later and there really isn’t any reason to begin at 7:00 AM. 9:00-10:30 AM - Reading. Ideally this is aimed at current local, national, international, or global problems with current events from the news or other texts. The goal is simply to be aware at the beginning of each day of the suffering that is taking place all around us. This is not done to instill pessimism, but to inspire compassion - the desire to alleviate suffering in others. Literature that deals with human created suffering such as Frankenstein make for good selections during this time as well. Conversation. This is a time to discuss what’s been read and share what interests and engages us. There can be a specific topic for this first hour, say sex trafficking of women around the world, or more open-ended reading of current affairs and sharing issues of personal interests. The aim is simply to engage in meaningful conversation about the state of the world with the purpose of refining ever more acutely what causes suffering and understanding the variety of contexts that contribute to it. Investigation. This is a time to investigate what solutions have been generated for the causes of suffering we’ve been reading and discussing and to figure out what we can do as individuals, a group, and a community (both locally and societally) to alleviate it. This should spur lots of insight and opportunities for the social entrepreneurship block to come later in the day as possible gaps are identified in current attempts to deal with issues. Students might investigate political, economic, social, or technological solutions that have been attempted to deal with world problems. 10:30-11:00 AM - Break. This is a time to simply relax, have a snack if needed and transition to the next phase of the day. 11:00 AM-12:30 PM - Physical education. This is a time for strength training, cardiovascular training, mobility training, and other athletics. This is also an opportunity to meet in small groups or one-on-one to discuss nutrition, mental health, and emotional health in order to increase and monitor overall well-being. The aim is pragmatic, how do we take care of ourselves as humans? 12:30-1:10 PM - Lunch. 1:10-2:40 PM - Social entrepreneurship. This is a time to work collaboratively on projects that aim to alleviate suffering and improve the world. Creativity, service, design, innovation, STEM, and business skills are intermingled in order to develop projects and programs that would have the greatest possible impact in any particular area. All members of the school community spend this time actively engaged in social entrepreneurship work, which could also include supporting one another’s enterprises, meeting with community partners and facilitators, and working off campus. This is also an opportunity to attend roundtable discussions to present work completed so far and elicit feedback from others, as well as figure out collaborative partnerships. 2:40-3:00 PM - Break. 3:00-4:30 PM - Personal growth and well-being. This is a time to end the day on a positive note, examining personal strengths, goals, and psychological states. This is also time to follow individual passions, such as reading literature, playing music, learning languages, creative writing, playing sports, making videos, blogging, or simply relaxing. The rejuvenation that comes from this part of the day will help the following day to commence with similar excitement. Engagement and flow should occur often and students can leave for the day feeling charged and full of zeal. A Day in the Life of a Student “Air pollution increases amidst warnings.” “Migrants face deportation.” “Refugees seek urgent medical care” Maia stretches and looks up. It’s nearly 9:30, the end of the half-hour reading block that begins the day. Maia, her peers, and their teachers have been together as a team for the past year and a half. While they don’t always agree on how to most effectively tackle the suffering in the world, they care for each other and about those around them. Soon, there’s enough movement to indicate that the readers are ready to talk. They readjust themselves around the room, remaining comfortable, but better able to see and hear each other. “I’ve been reading a lot about climate change today.” The comment comes from a student perched on an ottoman next to a stack of books with titles like The Age of Sustainable Development. “Did you see the New York Times article on the summit?” Maia asks, still sitting against the wall. “There’s a picture of the Doomsday Clock in my head.” “I thought Canada put up a particularly strong stance, actually, and that might push other countries to follow through with caps on emissions.” A student new to the group states, sitting at a desk. “That’s pretty broad, though,” says a student on the floor near Maia. “Yesterday, I read a lot of this book on the Copenhagen Consensus and there are real proposals that real people are working on, but it’s hard to tell whether emission caps are actually more effective than other suggestions, like bioengineering. On the one hand, it’s an easier sell. So maybe that’s better than nothing.” The conversation continues for about thirty minutes and covers a range of topics from climate change to micronutrient deficiencies in small children. As always, the focus is on understanding why suffering occurs. Gradually, students return to their laptops and put in headphones, ready to move on from discussion. Feeling agency to act is important. Maia and several classmates have lately been investigating vaccination efforts in Africa. They read Half the Sky together earlier in the year, which prompted questions about sex trafficking due to poverty, leading to a foray into tropical diseases. When they come across a new report on Ebola, one group member calls over a teacher to ask about virus mutations while others gather around a YouTube video explaining the science. After about thirty minutes, it’s time to stop. Maia has learned to monitor her body for fatigue and tries to pause in her work before reaching a point of frustration. While some stay to continue working, Maia needs a half-hour of relaxation and maybe some frisbee. She takes an apple out of her bag and joins a loud group of friends on their way outside. Frisbee leaves Maia feeling warmed up and ready to keep moving. She has a meeting with a nutrition counselor at 11, the beginning of the physical education block. After a long exploration of ethics and sentience, Maia has decided to become a vegetarian and wants guidance on her new diet. If she can’t take care of herself, she can’t make the world a better place. A guidance counselor taught her that last year after she experienced a series of anxiety attacks. After her meeting, Maia joins a group of classmates for a trail run in the woods on the edges of campus. When they get back to the gym, Maia heads straight to her favorite coach. She wants to add mobility training to keep her hips mobile for the barbell squats she already does with the hope of squatting one and a half times her own body weight. She found a series of exercises online and asks for help with her form. The gym begins to clear out around 12:30 as students freshen up before lunch. The afternoon campus is unrecognizable from the calm of the morning. Teachers, students, and community members are everywhere, all working on a myriad of social entrepreneurship projects. Maia’s group is putting together an education campaign about vaccination. They've partnered with another group focusing on fundraising efforts to implement the campaign. Each group takes a turn updating the other on what they’ve accomplished since their last check-in two weeks earlier. A teacher joins the groups to ask whether they’ve contacted any humanitarian aid agencies, which Maia’s group adds to their task list. Across the room, a few students and teachers are gathered around a whiteboard with a series of questions: “How do we create vaccines? What are they? Are there vaccines we don't have, but would like to have? What's been done to create them? Can we try making one?” Pointing this out to her group members, Maia joins in the discussion. This could be another good partnership. It’s 2:45 by the time Maia’s group decides to stop for the day. They have a “next steps” action plan that should get them through the rest of the week. Other groups have already paused in their social entrepreneurship work and gone back outside to take a break. Maia returns to her locker for her yoga mat and makes her way to an open studio space. After learning about yoga and meditation from a friend last year, Maia started an afternoon yoga class during the personal growth block. At the beginning of class, she invites each person to check in with themselves and set an intention for their practice. They’ll be in this space for an hour so she encourages them to focus on altruism, approaching each person with the goal of enhancing their overall well-being in every interaction. After class, Mais steps over a robot whizzing down the hallway and follows the sounds of yelling and cheering to a room at the end of the hall. Someone mentioned a new virtual reality video game and maybe these are the people to ask about it. At 4:30, Maia joins the waves of students leaving campus. She feels content, optimistic about the work she’s doing, and already looking forward to meeting with her project group again tomorrow. She makes a mental note to see what the team of teachers has been working on; she hasn’t really talked with them this week. Maia flips through her phone to a podcast recorded daily by a group of students. “Good afternoon,” the host begins. “Thanks for joining us on What to Be. Today’s special guest is the executive chef at a local restaurant that provides job training and childcare for mothers.” Maia smiles. That chef is a friend who graduated two years ago. Cool. Final Thoughts The actual blocked timing of much of this day ought to be more flexible than is written out here. It’s important that students learn how to manage their time and what is important. If they are fully wrapped up in a project they are working on involving social entrepreneurship, it is in no way urgent that they stop so they can move onto the final chunk of the day focused on personal growth and well-being; they are almost certainly already feeling a sense of personal growth and well-being if they are truly engaged in the project and feel a deep sense of meaning and purpose. Let them continue on. The shape of this day is designed so that students can be exposed to problems early, work hard on thinking about and reflecting on them, take a break to physically recharge with exercise and food, move onto solving problems and creating value in the world for others, and then finish with some personal “me” time that explores what gives each of us pleasure and a sense of well-being. They will be prepared to act as responsible citizens who can think critically and participate in civic debates while also being ready for employment that is purposeful and creative. When not acting as citizens or employees they will understand how to relax and enjoy themselves in personal activities that contribute to a sense of rejuvenation and flow. Learn, exercise, connect, create, be. Do our students really need to focus on anything else? Humans as social animals have several modes of interaction and many models have been created in attempts to categorize them. Fiske describes communal sharing, authority ranking, equality matching, and market pricing as ways that humans relate to one another. Graeber writes about communism, hierarchy, and exchange. Using Graeber’s model allows us to collapse Fiske’s equality matching and market pricing as two different forms of exchange into one category. Haidt says we rely on universal values of care, fairness, liberty, authority, loyalty, and sanctity. His research shows that conservatives reliably use and weight all six values more evenly than progressive liberals, who rely primarily on care, fairness, and liberty, which he interprets as conservatives having a more complete set of moral “tastebuds”. Greene builds on Haidt’s research in conjunction with Kahneman’s research on thinking fast and slow, to point out that our intuitive “fast” thinking often deals with the more conservative values of loyalty, authority, and sanctity, while our “slow” rational thinking often moves us beyond them to the more liberal values of care, fairness, and liberty. This movement into the slower, rational thinking allows us to cooperate with not just our own tribe members (i.e. “us”), but members from other tribes (i.e. “them”) as well by tapping into more utilitarian cost-benefit analysis of what will benefit us over the long run.

Lakoff simplifies all of these categories even more by developing what he calls “frames”. There are two basic frames - strict parent and nurturing parent. These, according to his research, fundamentally divide conservatives and liberals respectively and allow us to understand how various “wedge issues” are developed by both sides. All of this research is useful for understanding how humans interact. However, when looked at as a whole, I see two large divides: people that rely on exchange based utilitarianism and people that rely on hierarchical based duty ethics. The two closest models to this are Graeber’s comprised of communism, hierarchy, and exchange and Lakoff’s strict and nurturing parent frames. I believe the utilitarian exchange model of social interaction is one with substantially more benefits, while the latter is baser and often relies on violence to enforce the duty bound hierarchy rules. Violence All of the above is necessary information to discuss violence more generally. Resorting to violence effectively resorts to hierarchy, with “might makes right” being the highest decision making rule at the top of the pyramid. When two parties come into conflict they can choose to exchange conversation or use violence to resolve it. Those are our two tools. With violence, the person with the most might is always “right” and the person with the least might is always “wrong”. This results in taxonomies of power, with rulers on the top and the most oppressed and vulnerable at the bottom. This is why “liberty” doesn’t sit well with hierarchy and we use the term “liberated” for oppressed peoples that become free of the “might makes right” rule of interaction inherent in hierarchy. The liberation is that of a person who is free of violence or its threat and capable of entering into exchange based modes of interactions. These include the majority of social interactions that have caused human progress: free speech, freedom to experiment, freedom of assembly, freedom to enter into contracts, freedom to negotiate, and freedom to persuade others through rhetoric of better ways to live. This liberty is not necessarily in direct contrast to communism as Graeber uses it. In his model, communism is the approach to interaction where a person acts out of desire to do so with no expectation of something in return. There is no initial conflict or disagreement as with exchange or hierarchy. Person A: “Can you pass me that water bottle?” Person B: “Sure, here you go.” This is communism in its purist form, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need”. Person A “wants” the water bottle and Person B is able to provide it. What you don’t see is a response from the favor-doer asking the favor-asker what they will get in return, nor do you see the favor-asker forcing the favor-doer to do it as you would see in exchange and hierarchy respectively. Most familial interaction between parents and children is performed on the basis of communism. Parents do things for their children without the threat of force from the children or because they are hoping to exchange their services for ones provided by their children. It’s also how many strangers interact on the street when asked for directions or the time. We simply help because we are able to do so. It’s the bedrock of human interaction and the most prevalent in day-to-day life. The other two, hierarchy and exchange, are our options when we don’t want to help, interact, or do something that another is asking of us and they are the ones we must decide between when thinking about and discussing violence. Person A: “I think we should do X.” Person B: “I think we should do Y.” If we assume X and Y are mutually exclusive and have different outcomes, we must figure out a way to resolve this conflict. We can use hierarchy, which at its essence is a threat of violence or a resort to actual violence. “We will do X or I will hurt you. If you understand my threat is real, you can choose to acquiesce quietly or test my resolve and force me to actualize the threat into real violence.” Much of the world operates on this model to this day. See the wonderful book The Locust Effect for several hundred pages of current day examples of the billions of people living in poverty. However, we do not need to go into the world of poverty to see this effect. Any place where hierarchy exists, there is some threat, whether apparent, disguised, or hidden, of violence. Our schools are an excellent example of hierarchy backed by violence. Students are at the bottom, above them are teachers, then administrators, then superintendents, and somewhere higher up is the state. The state is commonly described as being the sole legitimate monopoly of force (violence). This means that students are ultimately compelled to act as they are told because of the threat of violence that exists from the state. Student: “I want to do X.” Teacher (State): “You must do Y or I (the state) will do A to you.” This is not communism or exchange. It is hierarchy and the threat of violence, thinly veiled. Exchange on the other hand is the heart of liberalism as embodied in democracy and capitalism when properly understood. Person A: “I want to do X because of reasons A, B, and C. All of the reasons A through C will benefit you greatly, even more than action Y that you want to do.” Person B: “I did want to do Y, but you have persuaded me with your sweet talk and rhetoric that X is better. Let’s do X.” This example is simplified and may even come across as silly, but is exactly what happens every time we interact and exchange with others. When we think of free-markets, the reason they are so beneficial is that no one forces you to purchase the products and services. We do so because we’ve been convinced to exchange our money (a store of value) for the benefits the goods and services provide. This exchange makes us better off overall. We have traded something of value (money) for something of benefit. Exchange doesn’t happen unless it is mutually beneficial, unlike enforced hierarchy that tends to benefit only one party at the expense of the other. Of course, some of these exchanges take place over much longer time periods and some require much more convincing. But remember, assuming a person doesn’t want to undertake the action of their own volition, we really only have two choices: discuss, dialog, persuade, convince, reason, sell, talk, OR revert to force. Liberalism and all the progress it has brought humanity is fundamentally premised on choosing the exchange option, on recognizing that persuasion is a more dignified and humane way of interacting in the world than using force. Liberalism doesn’t deny that force is sometimes necessary. The state has ushered in a great deal of security and the world is less violent now than ever before. However, it does make our choices clear - violence or persuasion. Seeing this clearly has many implications beyond the example of school used above. For exchange to work, people must become far more comfortable with the simple “live and let live” motto when they find themselves in disagreement. As a default mode of interaction, it requires people to lay violence aside as an option. Taking violence off the table makes it so people either spend the time convincing others they are right or walking away. No compulsion allowed. This makes people very uncomfortable and often quite hurt or angry when they don’t get their way. Self-righteous indignation is a common reaction for those who are unable to convince or resort to violence. That needs to be accepted and people should learn how to adapt to it. A person’s inability to cope with discomfort, a sense of being wounded, or anger is not a reason to resort to violence. When all people accept this, the world will be a much more peaceful place. Take this writing as my attempt at persuading you that the world of exchange is a better world. I recently had an abbreviated conversation on the death penalty. It never really finished and I’ve felt very unsatisfied since. So here are my thoughts.

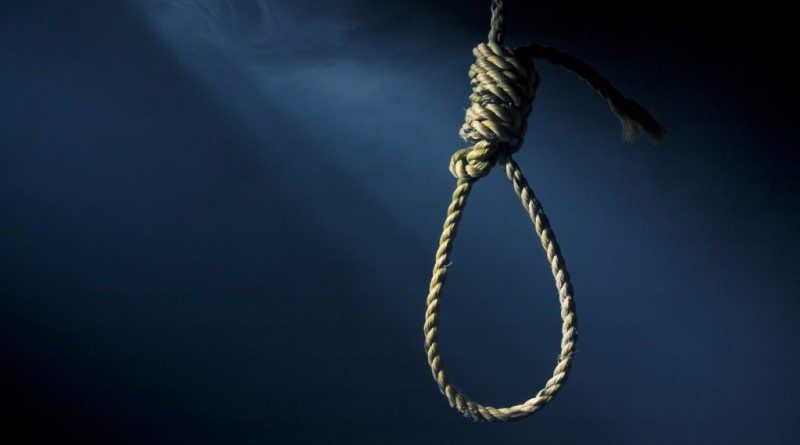

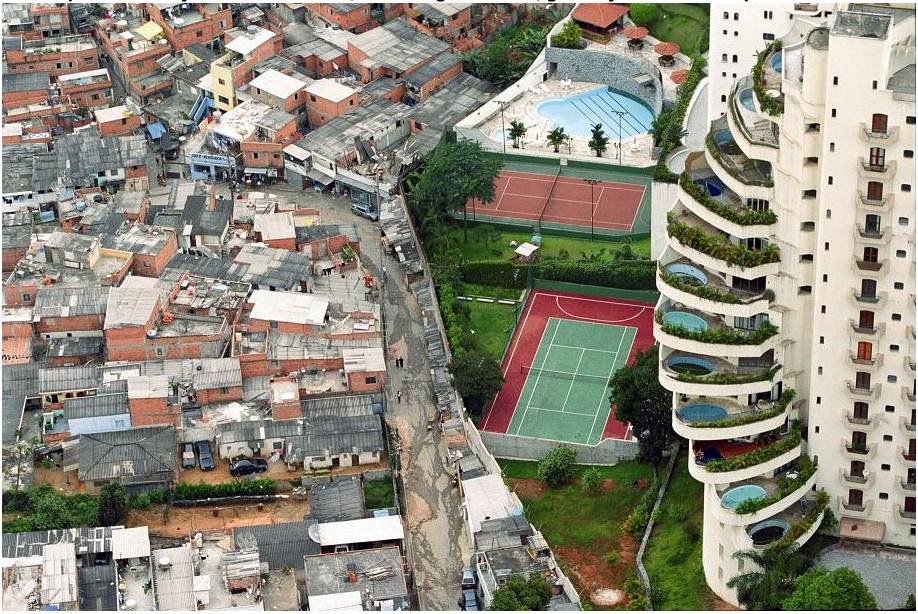

It is state-sanctioned revenge. An eye for an eye. It has little to do with justice or the safety of society, which is ensured as soon as the dangerous person is removed to a prison. I absolutely agree that some people are too dangerous to be allowed to live in society and must be separated for everyone else’s sake. That’s fine. Outside of the view that it isn’t related to “justice”, another obvious reason for not using capital punishment in the United States (I’m unfamiliar with other countries, but assume it’s similar in liberal democracies) is that it costs more to put a person on death row instead of sentencing them to life without parole. If we are concerned with the costs of life without parole, I see no reason to not allow inmates to work well paying jobs that allows them to pay their own costs, just like normal people in society. The only difference is they won’t be intermixing. Independent prison economies could be run, not much different than other small scale economies. Some employers may even prefer this option as they would most likely score themselves a wage discount by employing felons. If inmates do not wish to work and refuse to do so, they are welcome to starve to death. However, that is not the only option available. The state could make assisted suicide an option and allow them to decide for themselves. Furthermore, there is not much in principle from stopping a state from revoking citizenship from a violent criminal who would otherwise be sentenced to life without parole and letting them be on their way outside the country. Obviously, a life outside your home country, without a passport or the privileges of citizenship, is extremely difficult. However, it would simply be one of several options that included the work and assisted suicide options. To my mind, that hardly makes it cruel or unusual and in most cases would not be opted for as it essentially sentences yourself to life as refugee without a camp to call home, most likely ending in death after prolonged suffering. The central issue for me is that as a full-grown adult, a person is entitled to life so long as they wish to stay alive. They are self-conscious, autonomous, and sentient. These characteristics make the death penalty of an adult fundamentally different from the abortion of a fetus, killing infants in certain circumstances, or pulling the plug on comatose and severely disabled adults who cannot make the decision to “unplug” themselves. Therefore, the death penalty should not be used for both ethical and economic reasons, both of which are utilitarian in their own way, but that in no way precludes killing of others in specific circumstances or endorses the stance that “all life is sacred”. My last article focused on inequality being a problem of belief. Much like slavery, colonialism, and discrimination changed when we changed our beliefs about them, inequality will automatically be “fixed” when we believe differently about it. A single paragraph from that article captured the whole idea, Ultimately, this means finding a motive for the doing. Unless we are motivated to give and redistribute, we cannot “fix” poverty and inequality. The desire to change comes before the action and solution. This desire comes from our beliefs about the world and how we do or do not see ourselves as humans. It gets directly at the heart of how we see human nature. This begs the question, how do we change belief? Facts and rhetoric. So let’s try to understand some facts about inequality with the rhetorical intent to change beliefs. A secular, liberal, democratic nation grants individuals “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as “unalienable rights”. This supposes that a nation is fundamentally concerned with the well-being of individuals. What are the causes and conditions of well-being, and how does inequality affect total well-being in a nation? To answer the first half of that question, see my past articles on well-being, exercise, and education. The second half of the above question is of more concern here: how does inequality affect individual well-being? There are, in fact, a number of ways. Absolute poverty. Inequality that exists simultaneously with absolute poverty affects who lives and dies. Absolute poverty is defined as the minimum amount needed to meet basic human needs for items such as water, food, clothing, and shelter. This is often calculated by international organizations to be near $1.90 per day. This is adjusted for purchasing power and is therefore equivalent to what can be bought in America for $1.90 per day. Naturally, this bare minimum does not leave much margin of error. The author of The Locust Effect summarized this point well, I recall the way an old history professor of mine defined poverty: He said the poor are the ones who can never afford to have any bad luck. They can’t get an infection because they don’t have access to any medicine. They can’t get sick or miss their bus or get injured because they will lose their menial labor job if they don’t show up for work. They can’t misplace their pocket change because it’s actually the only money they have left for food. They can’t have their goats get sick because it’s the only source of milk they have. On and on it goes. Of course the bad news is, everybody has bad luck. It’s just that most of us have margins of resources and access to support that allow us to weather the storm, because we’re not trying to live off $ 2.00 a day. (p. 104) Naturally, this puts a very distinct damper on well-being. Inequality simultaneous with absolute poverty allows needless death. Very bad for well-being indeed.

Relative poverty. Even if the world’s rich were able to change their belief about absolute poverty being morally acceptable and decide to eliminate it through charitable giving or tax redistribution, we would obviously still live in a world with relative poverty. By definition, this will always exist so long as perfect equality does not exist. It is worth noting here that I am not arguing for perfect equality, just examining the impact of various degrees and types of inequality. However, one common finding within psychology is that day-to-day contentment doesn’t begin to plateau until around $75,000 per year. We can then imagine a nation in which the bottom 20 percent live on roughly $30,000 per year and the top 20 percent live on incomes of $200,000 per year. This is purely hypothetical, but not unreasonable. Knowing the plateau line for day-to-day contentment and understanding its connection to well-being can lead us to the conclusion that overall well-being in the nation could easily be raised by redistributing income from the top 20 percent to the bottom 20 percent up to the point of $75,000 per year. This would involve taking $45,000 from each person in the top 20 percent and redistributing it to each person in the bottom 20 percent for an average income of $75,000 for the bottom 20 percent and $155,000 for the top. This brings the plateau level for day-to-day contentment to everyone in the nation, including the bottom, while not altering the fact that the top 20 percent are still well above that line. Political economy. Assuming no one lives in absolute poverty and relative poverty is at or above the plateau line, we would still have good reasons for worrying about inequality. Those reasons are related to political-economy. Namely its effects on economic growth and regulatory capture by plutocrats. Several sources were linked in the last article, but to save time, you can see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. Most of these are book length treatments of inequality and its impact on economic growth, race relations, politics, and globalization. In summarizing these sources, inequality can allow the rich to create laws, regulations, and policies that benefit themselves and allow rent to be extracted without value creation. This is free money at the expense of those below them. This type of rent extraction is zero or negative sum, rather than the beneficial positive sum interactions that result from “trade-tested betterment” more typical of properly functioning free-markets. Entrepreneurship. Beyond these more indirect impacts of inequality, perhaps the best reason to support minimum floors and prevent too much inequality is the effect psychological insecurity and a sense of scarcity have on entrepreneurship. By ensuring (and insuring) that people feel secure, entrepreneurship is increased. Providing this sense of security can be done through several mechanisms, including universal basic incomes, unemployment benefits, maternity benefits, or guaranteed access to food. When inequality is not dealt with, it is historically solved with violence from “mass-mobilization warfare, transformative revolutions, state collapse, and catastrophic plagues”. This happens to be exactly what Buckminster Fuller was thinking when he said, “We must do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest.” That is a fact, and it then begs the question, “How do we make sure we invest in every single one of those people such that all of society maximizes its collective ROI?” An equitable distribution from the top to the bottom can help maximize entrepreneurship by allowing those with ideas to fail safely in their attempts to commercialize them. And that is exactly what makes the world a better place to live - higher quality production of goods and services valued by a large section of consumers who are able to afford them. Instead of clinging to the belief that we must earn a living, we can begin to move into a world that makes it possible for everyone to be an entrepreneur and everyone is able to take a shot at improving the world. This freedom to pursue ideas, learn new things, and experiment can lead to what Stiglitz calls a “learning society” where both individual and collective well-being are maximized. Those are the facts. High inequality in a world with absolute poverty is equivalent to allowing needless deaths. High inequality in a world with relative poverty and median incomes underneath the plateau line for day-to-day contentment leaves potential well-being on the table. And lastly, high inequality in a relatively rich world can still lead to slower growth, political inequality, and less creative entrepreneurship, all of which leads to a less rich and developed world. As stated previously, this is not an argument for perfect equality. Perfect equality or an attempt at perfect equality has been shown under several communist regimes to slow growth even more dramatically than high inequality. It is simply a recognition that just because perfect equality is not the aim, does not mean high inequality is acceptable. High inequality is damaging and the more fully aware of its damages, the more likely we are to change our beliefs - just as we did with slavery, colonialism, and much of discrimination in the past. There is a lot of disagreement over whether inequality is a problem or not.

Economics would tend to frame it as an issue related to total welfare and its relation to growth. If inequality slows down growth, then it is an issue worth adjusting in order to speed up growth and maximize total welfare in the long-run. There is empirical evidence to support the claim that concentrated wealth and inequality does hurt economic growth. So from a purely economic viewpoint, it is an issue worth addressing. The majority of interventions to address this involve progressive taxation and redistribution of some kind. However, total economic welfare is not the sole basis for our decision making. We have a variety of values and the one in most obvious opposition to equality is that of freedom. This is where beliefs matter and what makes (in)equality a particularly thorny issue. I recently wrote about what constitutes progress. In that article, I pointed out that as we overcome more and more obstacles to progress (slavery, colonialism, discrimination), the next frontiers (poverty and inequality) cannot be addressed with the same tools as the past. The former obstacles are ones that can be fixed by securing rights, poverty and inequality fundamentally need one person to give up something (money) and give it to another. This involves doing something (giving money) as opposed to not doing something (enslaving, colonizing, discriminating). Ultimately, this means finding a motive for the doing. Unless we are motivated to give and redistribute, we cannot “fix” poverty and inequality. The desire to change comes before the action and solution. This desire comes from our beliefs about the world and how we do or do not see ourselves as humans. It gets directly at the heart of how we see human nature. Most essentially, we need to discuss what people deserve and why. If I ask you to give up your money and you believe that you deserve to keep it because you have worked hard for it, then we are at a loss for a solution unless we are willing to resort to violence (state backed force). So we must examine this most common defense of inequality, that people deserve to keep their money or wealth because of some variety of meritocracy. The most typical varieties of merit I come across are ones of intelligence, talent, and hard work. “I deserve to keep my wealth because I worked hard, am intelligent, and applied my talents to issues of value.” Intelligence and talent are often easy to deal with as forms of merit entitling someone to the rewards of income and wealth. A person does not choose their intelligence and talent levels in any given endeavor and so without personal choice or control in the matter, it is difficult to argue in favor of a “just deserts” mindset for things you did not in fact work for. You’re born into fortunate circumstances, so anything that comes your way has little to do with you and is just a fortunate happenstance. The third merit used as justification for inequality is typically hard work. This is centered at the heart of the debate over free will and its existence. Why do you choose to work hard? You are motivated. Why are you motivated? Personality, emotions, feelings, drives, social circumstances, parents, etc. None of the items one can point to in order to explain motivation for hard work are actually in one’s control either. You no more choose to work hard than you chose your intelligence or talents and if that is the case you don’t deserve to keep your income and wealth any more than a kid who inherits a million dollars from a parent. Now we can address the topic of inequality a little more clearly. Do you deserve your wealth and income? No. You are fortunate to have it for any of a huge variety of reasons: your parents, place of birth, intelligence, talent, hard work, personality, social relationships. Not a single reason is of your own doing because you did not choose or control these things. However, the act of being born is not asked for by anyone. No one is alive today because they consulted with their parents and decided it was in their best interest to come into existence. If parents are able to make this choice to have children through their own unilateral decisions, then it is fair to say that the parents do in fact owe the children as happy an existence as possible. To birth a child into suffering and not do everything possible to provide it with well-being is to commit one of the most awful atrocities thinkable. Seeing this perspective, it becomes very important to provide the means necessary to achieve well-being once alive. This involves clean air, water, food, clothing, shelter, healthcare, education, and the freedom to pursue happiness. This cannot be done in poverty and absolute poverty should be seen as one of the most serious moral failings of our time on the account that we have the choice to rid our planet of it and we have not done so. Do we deserve to be wealthy? No. Do we deserve happiness and well-being? Yes. At the most fundamental level, these answers reflect our beliefs in free will, entitlements, and suffering. When our beliefs change, inequality will change automatically. Until then, inequality will persist indefinitely regardless of the economic interventions initiated. In response to my last article on how beliefs and world-views affect our desires for the world we try to create, one reader wondered if the section on euthanasia and assisted suicide should apply to all people, even those who decided to end their life “on whim” with no medical reasons for doing so. My answer is yes. Here is what I wrote in the previous article on this subject. Euthanasia/Assisted suicide. Being liberal entails giving people control over their own bodies. Neither of these should be prevented in the case of a person who willingly wants to end their own life. The reason for wanting to do so is irrelevant. The choice to live or die should be seen as the preeminent liberal issue. I see this decision as similar to whether one wants to leave a party that is no longer interesting or enjoyable. If one finds themselves in the middle of a party and one wishes to stay, no problem. If one wishes to leave, no one else has the right to prevent you from so doing.

Of course, the people at the party may have less fun without you and they may miss your presence at the party, but that is not reason enough to force you, against your will, to remain. You do not owe them your presence, nor do you owe them your suffering for their benefit. If it is really important to the members of the party that you stay, then perhaps they should discuss with you what it is about the party that isn’t satisfying and what they can do to make it better and worthwhile to you. If the party does then change to your satisfaction, you will no longer have any desire to leave. This analogy may seem flippant, but I assure you it is not. Remember, I do not believe in any metaphysical reality beyond this material world. So if one chooses to end their life, they simply no longer exist. There is no regret, pain, suffering, or other negative qualities. Once you have checked out, you are not “missing” anything because there is no consciousness to do the missing. So the real issue is the people that are left behind who did not choose to end their life. The people who chose to remain at the “party”. They may indeed suffer as a result of your ending your life, just as the people who remain at the party may indeed suffer at your leaving. However, that is not reason enough to be forced to stay alive. It is reason enough to do all we can to make life worth living for all and to make all individuals experience the most well-being possible. This perspective actually forces us to consider how we care for others to a greater extent than the societal norm of suffering through life even when we don’t enjoy it. If we genuinely care and desire others to be happy and stick around, then just as with the party where we make it as attractive as possible for those we wish to stay, we will constantly examine the relationships we have with others. A person who ends their life on a whim with no medical reason is, to my mind, a reflection of the social world they live in. It is a strong rebuke of the circumstances they find themselves in and a clear statement that they were not having their needs met by those around them. Humans have a wonderful capacity to experience the sublime because of the social interactions they have. Love, joy, laughter, kindness, care, touch, shared experience. These things make the party worth attending. Each day is a chance to plan, create, and attend that party. When the option of non-existence is available, it is not enough to live a few good days or years and then quietly suffer until death. Each day must have something to look forward to, something worth living for. Ensuring the value of existence ought to be seen as a mutual and interdependent responsibility of the living, our greatest duty to each other. Failing to do so, it is perfectly rational to opt out. It is time we all accept this. This was another question posed to a room full of teachers that I was sitting in recently. Most started in with the simple, basic, and the unthinking answers you’d expect from teachers and/or parents.

Empathetic. Kind. Caring. You can fill in the rest. This was followed by the presenter saying that in hundreds of rooms around the world, all teachers want the same things for their students when they grow up to be adults. That statement is false. Period. We do not all want the same things because we do not all use these terms in the same way, nor do we even have the same reasons for why we want them as characteristics of future adults. Do we want empathetic adults so that they are kind and caring? What about the psychopaths who understand empathy quite well, but use it as a tool for manipulation? Do we want kindness and caring because they are gateways to heaven? What about those who value kindness and caring because of their effects on happiness in this world? Do the differences in motivation for these values have different outcomes? Of course. After hearing this question, I wrote down what I felt were more specific characteristics of adults that I would hope for. These included: Empiricist: As humans we are gaining ever more information and knowledge about what makes us happy and fulfilled. Positive psychology is showing us that positive emotions, low negative emotions, life satisfaction, autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations, self-acceptance, purpose and meaning in life, engagement in life, and accomplishment are key to optimizing well-being and pleasure. We should be aiming to increase these facets of life, so long as they aren’t to the detriment of others. Furthermore, suffering ought to be of prime concern as we know humans experience an equal amount of pain as much worse than the same relative amount of pleasure. Therefore, reducing a given amount of pain and suffering often does more to increase well-being than adding pleasure to an otherwise decent life. Hedonist: One needs a metric for constructing the “good”. Most people seem to agree that living a life solely consisting of being tortured is bad. It is painful and causes suffering of an immense magnitude. If we are able to agree on this simple statement, we can move forward with figuring out what is good and bad based on pain and pleasure, not very different from how the field of medicine proceeds. We do not need one definition of health to agree that life without disease and early death is not as good as a long life free of illness. What is a pleasure can then be determined through empiricism and weighted against the utilitarian consequentialism of others. Utilitarian: In trying to balance our own egoist pleasures with that of others, some type of system must be created to calibrate them. Utilitarianism does this. In theory, if not in fact, we can aim for constructing a world with the most pleasure in it, not hindered by idealism and theism. This will overlay with Rawlsian thinking on the “veil of ignorance”. (See below.) Essentially, we want a world with the most pleasure, i.e. good, for the most people, while minimizing the harm. Materialist: This follows along from the trait of empiricism. There is no empirical data that argues in favor of philosophical ideals or a metaphysical reality. However, we do know much pain, suffering, and death have occurred entirely due to idealism, with religious claims about reality being a specific subset of those idealist philosophies. Buying into utilitarianism and empiricism also buys into the fact that idealism seems uniquely able to cause pain, suffering, and death. The data (history) is quite clear on this. See the religious wars, Nazism, Stalinism, Maoism, and the Khmer Rouge among many others for examples. Liberal: In admitting that there isn’t necessarily one pathway to happiness in our lives and knowing that autonomy itself is a key factor in experiencing happiness, the freedom to pursue our own pleasures is paramount. Empirical data also shows quite clearly that freedom of trade, movement, speech, and ideas are keys to prosperity and the enrichment of quality of life and living standards. In principle, we want to allow anything within a given amount of acceptable harm to others. This acceptable harm is constrained by utilitarianism, empiricism, and Rawlsian thinking. Atheist: Many of these traits are interdependent on each other. For instance, being atheist is a product of being both materialist and empiricist. The burden of proof ought to be on the one making truth claims about reality. Given the thousands of claims to “know” about a metaphysical reality that are often mutually exclusive, they should all be disregarded until proven otherwise. There is simply no more or less likelihood that a Christian, Hindu, ancient Greek, or Roman god might exist. I could just as easily claim my shoe is all powerful and all knowing and that refusal to worship it is grounds for death. Rawlsian: In addition to the above and particularly with utilitarianism in mind, John Rawls’ “original position” is a method to ensure that people remain impartial by having them imagine that they design the rules of justice behind a “veil of ignorance”. The implication here is that you can make any rules you want, but you do not know ahead of time which position you will hold in society. This provides a measure of defense against abusing or otherwise oppressing the poor, disadvantaged, and underprivileged of a society. Essentially, this argues for maximizing the minimum within a society. There may in fact be more characteristics that I would want the children I teach to have as adults. These seem to be the basics I would hope for with a degree of reflection on values and what I see as the most fertile soil for a better, more peaceful world. Substituting any of these for their opposites will lead to more pain and less pleasure in this world, something I categorically oppose. Some Implications The above characteristics imply a different world than the one we currently live in. Some of the most important areas of impact would be: Economic policy. This would follow the general rule of maximizing growth rates whenever there isn’t a long-run trade-off from environmental damage or oppression of various groups. Poverty is a morally unacceptable tragedy in our world and the best way to fix it is to continue growing worldwide incomes. On a Rawlsian basis, we can maximize the minimum by increasing the total world income. Most of humanity lived in absolute poverty for most of human history. Free trade, free movement of labor, and the freedom to spread good ideas in the forms of technology and entrepreneurship have lifted over ninety percent of the world out of poverty. This is one of the single greatest triumphs in history. On this topic, economic policies would need to utilize empirical data to actually be selected so specifics would vary. Foreign aid. In many underdeveloped and poor countries where the bulk of the absolute poor live, a single dollar can literally have one hundred times the impact that it does in a rich, developed country. If we are concerned with utilitarian hedonism, we would be obliged to donate much more in foreign aid than we currently do as a world. Approximately 700 million people still live in absolute poverty, something that can be solved with roughly 78 billion US dollars. This seems an obvious moral imperative if ever there was one. People should not be dying prematurely or suffering from long bouts of easily preventable and fixable problems. Climate change. This is somewhat of a tough one. In a perfect world that was anti-natalist (see below), we wouldn’t have children and so we could simply have a giant party for the next one hundred years while experiencing as much pleasure and happiness as possible. We would follow all the recommendations from positive psychology above and become as well off as possible before the end. In reality, people will continue to have kids and given that they do, the empirical evidence is very clear that humans are causing increased environmental damage at an alarming rate due to increased greenhouse gas emissions and destruction of ecosystems. This will ultimately cause mass suffering and needs to be reversed immediately. Gender identity/equality. This is another issue that falls under liberalism and Rawlsianism. First, there is no reason outside of religious idealism for anyone to care about someone’s preferred gender identity. Second, gender equality is something any hedonic, utilitarian, Rawlsian would choose to endorse if they were constructing a society from scratch and didn’t know where they’d be placed. No impartial person would voluntarily wish to create a society where they might be less than equal for any reason based on atheist and materialist beliefs. They would simply have no skin in the game on this issue. Child birth. Coming into existence causes unnecessary suffering. If we wish to minimize needless suffering, we would default to having no children. This may not be intuitive and so I recommend reading either Better Never to Have Been or Having Children. Marriage. There would be little reason to get married. Without the religious history of the institution and no desire to have children, what would cause people to seek marriage? The whole idea would seem absurd. That isn’t to say that two (or more) people wouldn’t see or experience the pleasure of spending a life together. What it does mean is that there is no reason to have laws primarily aimed at protecting children in connection with marriage. Providing tax breaks and other incentives for two people to get together also seems somewhat strange given all of the above. It becomes little more than a corporation that is arbitrarily benefitting two people. Sexual taboo and adultery. Neither of these would exist. For one, adultery ceases when marriage ceases. For another, sex would be recognized as a pleasure that is to be indulged in whenever two (or more) parties are interested and consensual. Being materialist and hedonist, the only concern would be health and the wish to avoid long-term disease from short-run pleasure. Drugs. This topic would follow the same logic as sex. Drugs alter our physical experience in the world and as long as it is pleasurable and consensual, then there is no issue. The major issue would involve utilitarian calculus of my pleasure at the possible expense of others (e.g. medical care, disease, and crime from hard drugs). In a fully informed world, we would also weigh our long-run health against our short-run pleasure as with sexual activity above. Abortion. In a world without an dualism of body and soul, there is no natural barrier to abortion. Aborting a pregnancy would not be seen as sinful, as all actions would be recognized as being a trade-off in utility. Without any religious idealism or metaphysical beliefs, abortion would not be the same issue it is now. Since we would already see coming into existence as being against that potential person’s best interests, we would take appropriate measures (as early as possible). Euthanasia/Assisted suicide. Being liberal entails giving people control over their own bodies. Neither of these should be prevented in the case of a person who willingly wants to end their own life. The reason for wanting to do so is irrelevant. The choice to live or die should be seen as the preeminent liberal issue. Death penalty. On the other hand, taking away a fully conscious and sentient life should not be allowed by anyone. If an adult does not wish to die, no one should force the end of their life. This differs from abortion in that the level of “personhood” is much more mature. Both consciousness and sentience have completely developed and they are able to make decisions about how life and death affect their own and others’ pleasure and pain. Their embeddedness in a social reality is much more established as well, and so the negative consequences are much higher than eliminating a small group of cells. Torture. This can be discussed in two different ways. We can discuss it as a thought experiment in which torturing a person would prevent a large-scale catastrophe and thereby prevent more suffering than it inflicts. This is the utilitarian approach that would essentially consent to the benefits of torture. However, we can also look at it empirically and point out that torture in reality has been shown to be ineffective. There is no proof of its efficacy and it is simply not worth pursuing the pain and suffering of a person for an ideal that has been proven again and again to be ineffective. In this sense, it’s much like the idealism of religion and nationalism. It must be discarded after finding no proof of its benefit and much proof of its harm. Gun control. The empirical data is pretty clear on this. More pain and suffering, mostly in the forms of being shot or killed, exist because of access to guns. This obviously doesn’t include the intimidation and fear that many may experience without ever being shot or killed because of someone with access to a gun. The benefits of gun control would only increase by including the subtraction of those experiences as a result. Conclusion Having gone through as many of the central issues as seems pertinent, it should seem clear by now that listing characteristics we want the children we’re teaching to have as adults such as being empathetic, kind, and caring is not useful. I believe that everything described above creates a world with the most actual empathetic, kind, and caring people in it by my viewpoint. Obviously, not everyone agrees. The more we continue to believe and say that, “we all want the same things,” the more we will continue to avoid discussing actual issues and attempting to solve them. Issues ought to be tackled one by one, but all issues will be tackled based on some sort of worldview and belief system. Treating them as all identical with identical desires makes this less clear. I am open to change my position on any of these larger viewpoints, but I would like to see rational evidence and reasoned arguments. Arguing from metaphysical superstition will immediately disqualify your opinion. And that’s the point. Until the actual rules of the game are laid out, we aren’t actually all playing the same game. We might pretend that we are, but we are actually working from very different sides of the issues. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed