|

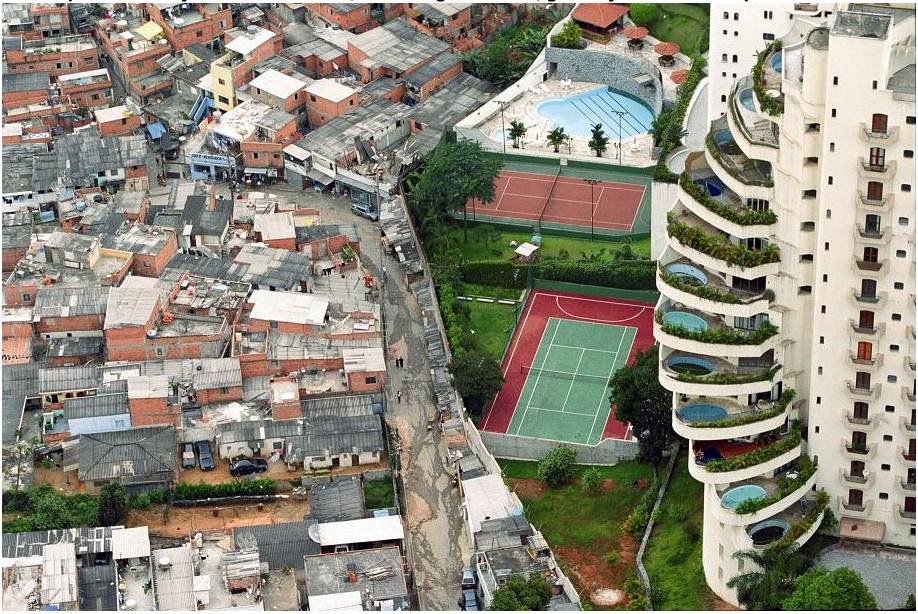

My last article focused on inequality being a problem of belief. Much like slavery, colonialism, and discrimination changed when we changed our beliefs about them, inequality will automatically be “fixed” when we believe differently about it. A single paragraph from that article captured the whole idea, Ultimately, this means finding a motive for the doing. Unless we are motivated to give and redistribute, we cannot “fix” poverty and inequality. The desire to change comes before the action and solution. This desire comes from our beliefs about the world and how we do or do not see ourselves as humans. It gets directly at the heart of how we see human nature. This begs the question, how do we change belief? Facts and rhetoric. So let’s try to understand some facts about inequality with the rhetorical intent to change beliefs. A secular, liberal, democratic nation grants individuals “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” as “unalienable rights”. This supposes that a nation is fundamentally concerned with the well-being of individuals. What are the causes and conditions of well-being, and how does inequality affect total well-being in a nation? To answer the first half of that question, see my past articles on well-being, exercise, and education. The second half of the above question is of more concern here: how does inequality affect individual well-being? There are, in fact, a number of ways. Absolute poverty. Inequality that exists simultaneously with absolute poverty affects who lives and dies. Absolute poverty is defined as the minimum amount needed to meet basic human needs for items such as water, food, clothing, and shelter. This is often calculated by international organizations to be near $1.90 per day. This is adjusted for purchasing power and is therefore equivalent to what can be bought in America for $1.90 per day. Naturally, this bare minimum does not leave much margin of error. The author of The Locust Effect summarized this point well, I recall the way an old history professor of mine defined poverty: He said the poor are the ones who can never afford to have any bad luck. They can’t get an infection because they don’t have access to any medicine. They can’t get sick or miss their bus or get injured because they will lose their menial labor job if they don’t show up for work. They can’t misplace their pocket change because it’s actually the only money they have left for food. They can’t have their goats get sick because it’s the only source of milk they have. On and on it goes. Of course the bad news is, everybody has bad luck. It’s just that most of us have margins of resources and access to support that allow us to weather the storm, because we’re not trying to live off $ 2.00 a day. (p. 104) Naturally, this puts a very distinct damper on well-being. Inequality simultaneous with absolute poverty allows needless death. Very bad for well-being indeed.

Relative poverty. Even if the world’s rich were able to change their belief about absolute poverty being morally acceptable and decide to eliminate it through charitable giving or tax redistribution, we would obviously still live in a world with relative poverty. By definition, this will always exist so long as perfect equality does not exist. It is worth noting here that I am not arguing for perfect equality, just examining the impact of various degrees and types of inequality. However, one common finding within psychology is that day-to-day contentment doesn’t begin to plateau until around $75,000 per year. We can then imagine a nation in which the bottom 20 percent live on roughly $30,000 per year and the top 20 percent live on incomes of $200,000 per year. This is purely hypothetical, but not unreasonable. Knowing the plateau line for day-to-day contentment and understanding its connection to well-being can lead us to the conclusion that overall well-being in the nation could easily be raised by redistributing income from the top 20 percent to the bottom 20 percent up to the point of $75,000 per year. This would involve taking $45,000 from each person in the top 20 percent and redistributing it to each person in the bottom 20 percent for an average income of $75,000 for the bottom 20 percent and $155,000 for the top. This brings the plateau level for day-to-day contentment to everyone in the nation, including the bottom, while not altering the fact that the top 20 percent are still well above that line. Political economy. Assuming no one lives in absolute poverty and relative poverty is at or above the plateau line, we would still have good reasons for worrying about inequality. Those reasons are related to political-economy. Namely its effects on economic growth and regulatory capture by plutocrats. Several sources were linked in the last article, but to save time, you can see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here. Most of these are book length treatments of inequality and its impact on economic growth, race relations, politics, and globalization. In summarizing these sources, inequality can allow the rich to create laws, regulations, and policies that benefit themselves and allow rent to be extracted without value creation. This is free money at the expense of those below them. This type of rent extraction is zero or negative sum, rather than the beneficial positive sum interactions that result from “trade-tested betterment” more typical of properly functioning free-markets. Entrepreneurship. Beyond these more indirect impacts of inequality, perhaps the best reason to support minimum floors and prevent too much inequality is the effect psychological insecurity and a sense of scarcity have on entrepreneurship. By ensuring (and insuring) that people feel secure, entrepreneurship is increased. Providing this sense of security can be done through several mechanisms, including universal basic incomes, unemployment benefits, maternity benefits, or guaranteed access to food. When inequality is not dealt with, it is historically solved with violence from “mass-mobilization warfare, transformative revolutions, state collapse, and catastrophic plagues”. This happens to be exactly what Buckminster Fuller was thinking when he said, “We must do away with the absolutely specious notion that everybody has to earn a living. It is a fact today that one in ten thousand of us can make a technological breakthrough capable of supporting all the rest.” That is a fact, and it then begs the question, “How do we make sure we invest in every single one of those people such that all of society maximizes its collective ROI?” An equitable distribution from the top to the bottom can help maximize entrepreneurship by allowing those with ideas to fail safely in their attempts to commercialize them. And that is exactly what makes the world a better place to live - higher quality production of goods and services valued by a large section of consumers who are able to afford them. Instead of clinging to the belief that we must earn a living, we can begin to move into a world that makes it possible for everyone to be an entrepreneur and everyone is able to take a shot at improving the world. This freedom to pursue ideas, learn new things, and experiment can lead to what Stiglitz calls a “learning society” where both individual and collective well-being are maximized. Those are the facts. High inequality in a world with absolute poverty is equivalent to allowing needless deaths. High inequality in a world with relative poverty and median incomes underneath the plateau line for day-to-day contentment leaves potential well-being on the table. And lastly, high inequality in a relatively rich world can still lead to slower growth, political inequality, and less creative entrepreneurship, all of which leads to a less rich and developed world. As stated previously, this is not an argument for perfect equality. Perfect equality or an attempt at perfect equality has been shown under several communist regimes to slow growth even more dramatically than high inequality. It is simply a recognition that just because perfect equality is not the aim, does not mean high inequality is acceptable. High inequality is damaging and the more fully aware of its damages, the more likely we are to change our beliefs - just as we did with slavery, colonialism, and much of discrimination in the past.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed