|

“Do we have to be able to draw a eukaryotic cell?”

“Ha, yeah.” “Oh god, I should’ve actually studied.” This type of studying is similar to crash dieting. “Oh god, I’ve got a wedding this weekend I need to be five pounds lighter for so I can fit in my suit.” Initiate last minute starvation and dehydration. Once at the wedding, eat and drink all you can until you pass out in the car on the way home. Wake up no better off than you were the week before. If we just imagine doing this every week of the year, the ups and downs would clearly represent an unhealthy approach to food and health. Yes, perhaps I can make my goal weight every weekend so I can reuse the same suit all year, but I’m likely to be more worn out and worse off by the end of year. I don’t think this is much different from the studying the students above are demonstrating. Crap, I have to consume this information so I look good on my test next period. Phew, now I can return to my junk food diet of YouTube and Instagram. Shoot, I have another test tomorrow. I’ll cram for an hour and reward myself with two hours of Call of Duty. It might seem a little different because we expect information to be more permanently retained than the ice cream we had last night. We can always exercise the ice cream away, we can’t exercise the information away. That isn’t very true though. Some information will stick permanently, but the vast majority of it won’t. Knowledge is physical. It can degenerate just as much as the rest of your body. Neurons that aren’t fired become weak. More importantly, just like yo-yo crash dieting, it engenders the wrong attitude. When we see good, healthy food as depriving us of other food we like, we can’t focus on the fact that healthy food can actually taste really good and keep us feeling good with a more stable mood. Once we switch from viewing healthy food as a deprivation to viewing it as what gives us everything we want, it’s no longer dieting. It’s becomes the way we eat. Our diet, not a diet. The same is true with learning new information. If we view learning as a state of deprivation, as taking away from time better spent doing other things, we have a difficult time seeing that we can view it as one of the most enjoyable activities. Learning new things isn’t a chore like eating celery, it’s invigorating - like eating celery! It’s fresh, tastes good, and leaves us feeling better off. I had the exact same attitude towards school as these students. I understand the sentiment. I just hope they find some area that does hook them and keep them going, regardless of whether it’s in school or not. I found a love of learning through fiction reading outside of school and in some great university classes in undergraduate, but for 18 years, I was just like them.

1 Comment

It’s time for progress reports again. That means I have a ton of students hyper-concerned about their current grades.

I hate it. I hate it every year. Every quarter. Their bodies physically transform in front of your eyes when they see their mark and it’s less than they had hoped for and desired. They shrink. They deflate. They do this because they believe, with the help of adults around them, that their grades tell them something about themselves. They really don’t. Grades transfer very little to anything else in life. Lebron James isn’t successful because of his grades. Bill Gates isn’t successful because of his grades. There’s simply very little crossover. Your parents do say a lot about your life chances. They transfer their genes to you and usually decide your geographic location for much of your upbringing. These are the two largest determinants of your future income and many markers of success, however defined. Your grades are often just a reflection of these two factors and the extent they predict anything, it’s almost certainly because of them. If a kid gets a grade lower than they want, the answer isn’t to deflate or shrink, it’s to pivot or grind. Pivot to something else entirely, something they have a relative advantage in. Being really good at math is certainly lucrative and provides an opportunity for money, fame, and personal engagement or meaning. But so does making funny YouTube videos, which requires no math at all. Seriously, who gives a fuck. Stop with the attention on grades. There are roughly six subjects taught in school and that means there are roughly six ways to feel successful in school. There are an infinite number of ways to feel successful outside of school in actual life. Decrease the importance of those six topics if you aren’t as good as you’d like to be and figure out an alternative. I promise there is much more success to be found in non-traditional areas than the conservative hallways of a school. By the time anything makes it into a school, it’s more or less dogma and “figured out”. That means there’s very little space to navigate successfully as an innovator or pioneer. Focus on what you’re interested in and spend ten hours a day grinding away at that. By the time you finish school, you’ll have accrued thousands of hours doing that thing and hopefully be one of the few people in your class even decent at it, rather than half decent at the same thing as all your classmates who learned the same thing as you in all their classes. This makes you unique and potentially valuable. Schools no longer have the monopoly on value they once did. People are becoming highly engaged, self-actualized and fulfilled millionaires every day on the internet by providing products and services to very niche markets. Find your market. Develop 1,000 true fans and sell them a few products a year until you die. You’ll be connected with them. You’ll have purpose. You’ll also have a 1,000 bosses and not one. If one doesn’t like you, your life continues on more or less uninterrupted. What could be better? School doesn’t say much about you because school gives you very little of what will make you “you” in adulthood. Don’t take it as something that decides who and what you’ll be. There’s no need to deflate because there’s little that will transfer. Transfer is a myth. There is a student that sits outside the elevator I take up to my office each morning. He sits there on the ground practicing his violin and has been doing this for over two years now. When he began, it didn’t sound very good. Lots of false starts and missed notes. Now it sounds pretty good. He’s not ready for Carnegie Hall, but he is making music, not just sound and noise.

In the past couple weeks, several teachers have commented to me, while crowded in the elevator on way up, about how much he has improved. Some have mentioned that they wished they had a ten second audio clip from each day to see how it has transformed over the past year. And it has. It’s great to hear and I’m happy for him. This isn’t about him though. It’s about the teachers, the staff, and the rules that exist in schools. Everytime someone makes these comments, I internally ask myself, “What would they be saying right now if it had been the drums? Or hard, metal rock with an amp? Or, heaven forbid, a kid rapping, hoping to be the next Eminem or Jay Z?” The answer is obvious. There wouldn’t have been a year of improvement. There would have been a quick, “Sorry honey, you can’t practice that here.” There would have been action, without any sympathetic thought, that it was best for all if he simply didn’t drum, rock, or rap there. This type of discrimination is what schools do very well. We decide what is acceptable. What’s okay. Then, we simply disallow anything else. We close off the possibilities before they even begin and make sure the creativity and expression is within whatever realms we deem digestible and proper. It makes me upset each time I hear him now. He has become an auditory symbol of all the possibilities that aren’t allowed, “because.” So every morning I start my day with a little bit of sadness, knowing that for some, or perhaps many, of our kids, it will be another day where we kill just a little bit of whatever they’re passionate about and get them one step closer to conformity what’s expected of them. David Graeber writes in the concluding pages of Debt, “what else are we, ultimately, except the sum of the relations we have with others” (Kindle Locations 7961-7962).

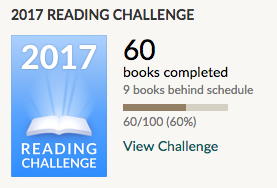

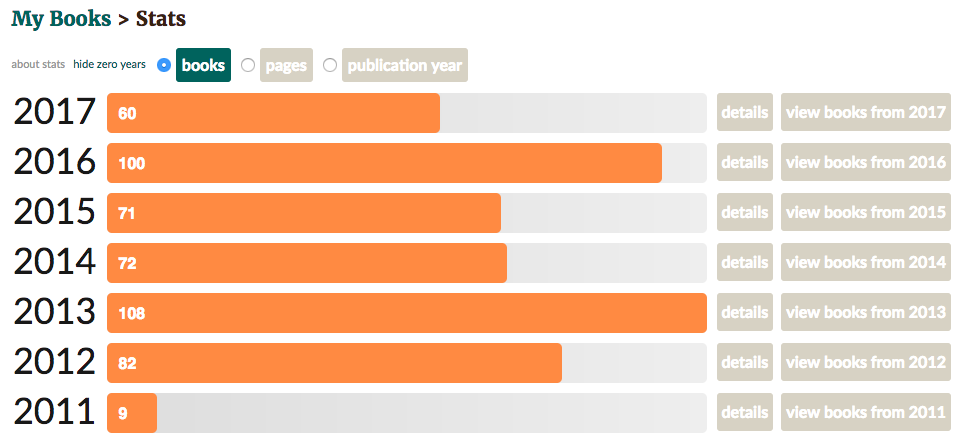

It takes nearly 500 pages for the reader to arrive at that sentence and fully feel the weight of it, but it is a question that decides how we wish to be in the world. For Graeber, there are three ways of interacting with the people around us: communism, hierarchy, and exchange. Communism is the “foundation” of human relations. We would not survive infancy and childhood without it. It is a system predicated on, “from each according to their ability, to each according to their need”. A mother does not provide for her child because she is looking for something “in exchange” or to show her superiority in the ladder of hierarchy. She does so out of love because she is able and the child is in need. This is how Graeber views communism when stripped from its political and historical connotations. Ultimately, it is an expression of love, benevolence, and kindness. There is no community on earth that could survive without it and all societies are built upon it. When engaging in this type of relation, debt doesn’t exist. Not really. Not in the form of specific quantification and the need for equivalence in repayment. There is clearly no equivalence between mother and child. They do not meet as equals and then decide to become indebted or not. Repayment doesn’t really begin to enter it. What would we think of the parent that tallied every service provided to their child and presented them with a receipt upon becoming an adult of all debts owed? They would be a monster in our eyes. Hierarchy and exchange are the two systems we use when we aren’t giving freely. Traditionally, hierarchy arises from differences in the status and power of people. Interactions are not among equals, but debts and levels of honor are maintained. One can increase their honor by taking it from those around them. The lord with the most honor is the one that maintains the largest number of people below them, able to strip them of honor at any time. Of course, all this maintenance requires large and frequent gifts on the part of the lord, but servility and obedience is expected in return. They are not the gifts of the mother and humility, degradation, and violence await anyone that decides not to repay with servility. Exchange is when people meet as equals. They may choose to take on debt and become unequal, but the possibility of repayment always holds out the idea that equality exists now or in the future. Of course, debt doesn’t have to be taken on at all and two people can simply exchange and part, no further relationship required. In that sense, exchange doesn’t require us to see each other as having relations at all. Our relationship ends as soon as our deal or debt ends. Understanding these modes of interaction helps the reader once Graeber begins describing money, which comes in two essential forms, credit or coin. Credit forces us to engage in relationships because of the necessity to extend trust when interacting. When we lose trust, we lose credit. Coinage, on the other hand, allows us to interact through pure exchange with no relationship. Graeber points out that the “military-coinage-slavery complex” can arise because of this aspect of coinage. Militaries of conquest can pay their soldiers with loot. In foreign lands with no relations, this loot can easily be turned into coin and no relations or credit are needed in order exchange goods and services. This often leads to slavery for a few reasons. Enslaving a conquered people entails stripping them of all ability to enter, form, and maintain relations with others. They are now objects, not human, and can become similar to the looted coin. They can also be harvested to create more coin and allow further military expansion. A slave can be seen as unfree because they have no relations or the ability to make them. Graeber notes that our somewhat strange definition of private property descends from Roman law which includes the right of dominia, the full right to use and abuse as the owner sees fit. This is a direct result of the extreme version of slave rights that the Romans had. Romans were allowed to literally do anything they wished with their slaves because they had dominia over them. This was not usual or common elsewhere, even at that time, because slavery was often a temporary condition and not lifelong. The right to use and abuse non-human property, such as a table, would hardly need the legal protection encoded in the right of dominia. In the end then, Debt is much more a book about what it means to be human than about anything financial per se. If we are to agree with Graeber about his classifications of the types of interactions we can engage in and the various outcomes that arise, we are presented with hard questions about ourselves. More than anything else, this book forces the reader to ask about the nature of violence in human relations and what exactly it means for our humanity. The ability to exercise violence strips me of the need to “see” you at all. On the other hand, if communism is our foundation and it is predicated on love, giving with no thought of repayment, then hierarchy and exchange both rely on either debt or payment instead. They rely on valuing and pricing, not the recognition that humans or relationships can in fact be beyond value or priceless. To put a price on something is, to a certain extent, to do violence as an alternative to acting out of love. Because we put prices on nearly everything, we have violence all around us. Admittedly, it is often tacit, hidden, and out of sight. Where do we find it? Laws, police, and prisons. If I am hungry and steal food without paying the stated price, violence will be done to me. If I seek shelter because I am cold and homeless without paying the proper price, violence will be done to me. Most of this violence is simply threatened, but it is real if we choose to ignore it. Even in our own houses, violence is a very real threat. Own your own home outright with no mortgage? Try not paying your property taxes one year. You will quickly find police force removing you from “your” home. When everything has a price, we aren’t required to empathize and sympathize with others as humans. We can always pay them if they’re a nuisance. This is strange though because payment is only simulated equivalence, not real, actual equality. Payment to another for injury, pain, or stress does not actually erase it. What is the result of all these payments without sympathy? Dehumanization. If the quote that began this post is true, that we are “the sum of the relations we have with others,” then we have decidedly less humanity when we forgo entering into sympathetic relations with others from a desire to love and not harm. With enough wealth, we can essentially sever all human relations because we have no need to rely and depend on others, we can simply pay for anything we wish. This, of course, is false precisely because we cannot in fact pay for our humanity. It arises out of those relationships we do form, not the ones we avoid, and the extent to which we are willing to extend love, trust, credit, and allow ourselves to become indebted to others in ways that are beyond repayment. Repayment we would never actually seek because to do so would be unhuman. This final thought is the central insight of the book. Being human is being indebted to everyone around us, but that does not require us to tally up our debts and seek repayment. Being truly human entails giving and receiving freely, which is also at the heart of being free. Being unfree is to be a slave, as we saw above, and to be no longer human. So far, I believe everything I’ve written to be true. However, this does present a problem and what I think is perhaps the key issue with modern life. For most of human history, we were poor, but free. Then we discovered the scientific method, the industrial revolution, and the rise of capitalism, which all led to wealth beyond imagination. Yet, it is extraordinarily difficult to imagine this system working without debt and hierarchy. Does this mean that we have bought our positive freedom, or the opportunities available to us, in modern life at the expense of our more basic human freedom? Is this a mandatory trade-off, having to give up genuine relationships predicated on love in order to set precise prices and debts that must be repaid, to enable massive increases in productivity and therefore wealth and income? Perhaps it is. Maybe humans are fated to exist as poor and free to engage in whatever relations they want or rich and enslaved to debt and masters. I truly don’t know, but I have a feeling it’s just a choice that we make. I think we can have both, but it means recognizing that certain things can’t be paid for or priced. Some things in human life should simply not rely on violence as the mediator. This will necessarily involve dialogue and some lost efficiency, but the human wealth we gain is likely more than worth any income lost. Every year I try to share with students as early as possible that I read a lot and that I like to exercise very much. Today, some of my students asked if I still read and exercise a lot, how much it cost me, and how I have the time. First off, I do still read and exercise a lot. Second, if I read between 70 and 100 books a year at somewhere between $10 and $20 per book, then it cost something like $1,500 a year. This kind of surprised them that I spent “so much” on books. The next question was about how I remember information if I consume so much of it. I try to be honest; I don’t remember everything. Sometimes I just remember a single idea. However, compared to my students, I genuinely do remember much more than they think is possible and that’s for one main reason - all of my reading is self-selected based on personal interests, usually involving questions I want to find an answer to. If I read an entire textbook on building muscle, for example, then it isn’t nearly as hard for me to remember that information as a student who is trying to memorize biological pathways in a course that is one of seven they have to take in order to graduate. (For the record, mechanical tension or “weight on the bar”, metabolic stress or “the pump”, and muscle damage are the three major known pathways to muscle growth in the literature.) With that aside, they wondered how I could read and exercise and work all day. My first, tongue-in-cheek reply was that I didn’t have to go home and take care of “one of them” after work ended like their parents did. However, that geuinely is a large part of it. I finish work at 4:30 pm and I have a gym that is about 60 seconds from my front door when I walk down the street. My home is about 12 minutes walking from work. Therefore, I can be at the gym exercising by 4:45 pm on most days. This gets me home by 6:00 pm most nights and I exercise Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, with some less structured, “free” workouts on the weekends when I feel the urge. If I then shower and eat dinner, which is often either delivery or made by my lovely wife, I can then relax for several hours. Those several hours are typically a couple hours of TV and one to two hours of reading as I fall asleep. So even in a typical 42.5 hour work week, I can go to the gym four times and read for five to ten hours with very little trouble. And of course, I have the whole weekend to indulge in more reading, exercising, or relaxing as I see fit! The weekend is when I typically do a lot of my writing if it’s been a busy week. Beyond simple habits of routine, I do use several tools to help me ensure that I get this all done and “stay on track” because I simply don’t like taking it for granted that I will do these things. After all, even though I enjoy reading difficult non-fiction, squatting heavy things, and writing long articles, they are activities that are inherently difficult and increasingly so over time as texts and weights become tougher. Here are the tools most useful for me:

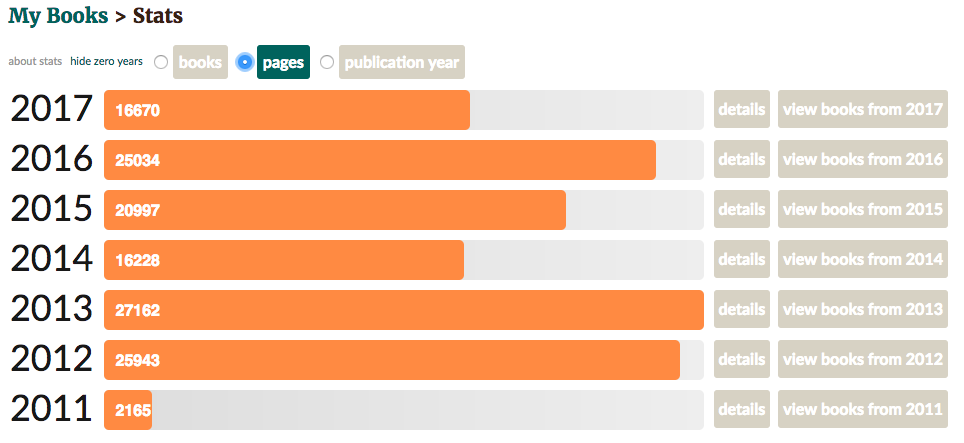

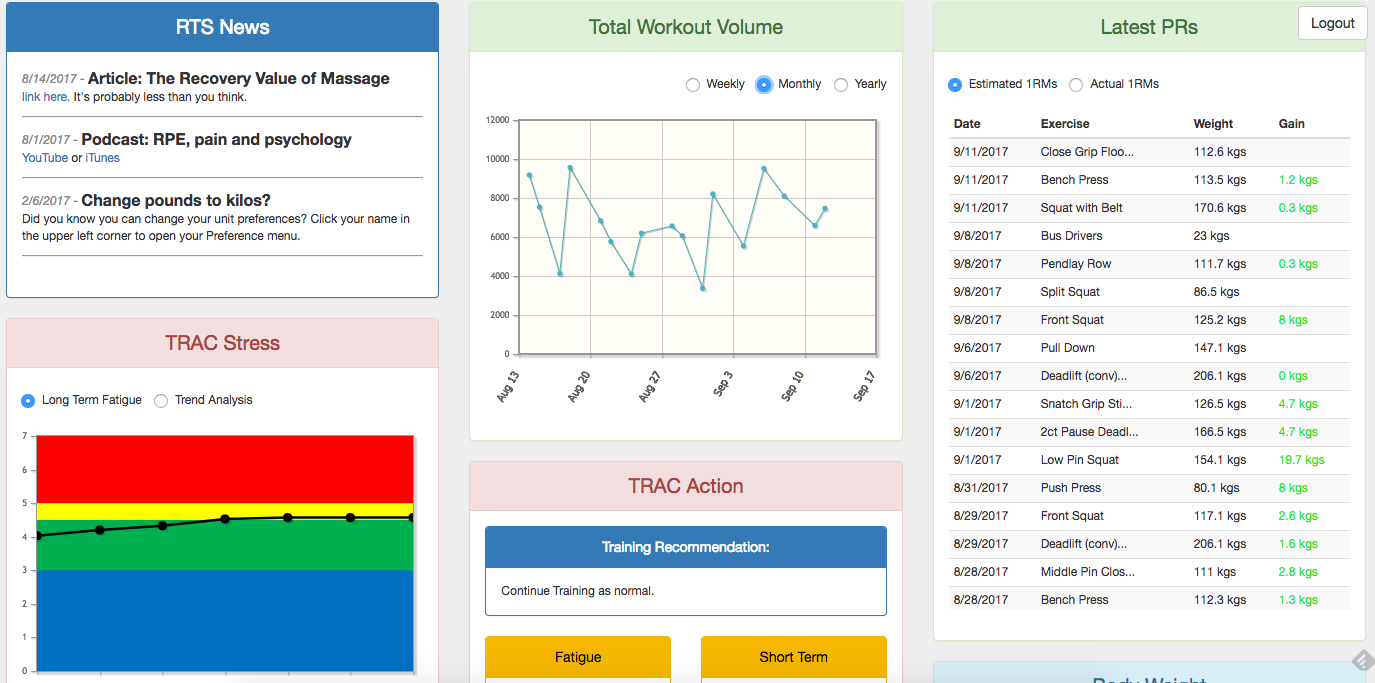

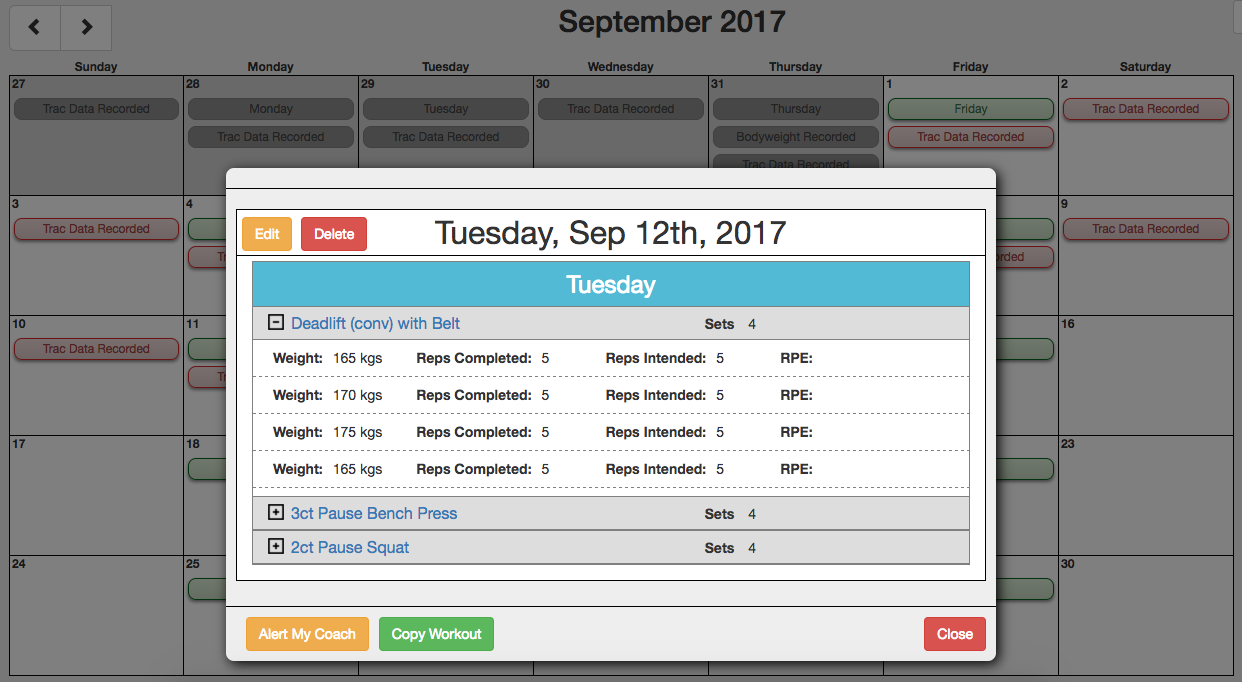

Those are the relevant dashboard stats on my Goodreads page. They tell me that if I want to finish 100 books this year, I am currently 9 books behind schedule. I've been aiming for 78 (1.5 per week), so I am actually 6 ahead at the moment, but changed it for this post to see where I'm at. The two images below that show my total books and pages read, both this year and years past, which helps for comparison and goal setting. The two images above are from the Reactive Training Systems Dashboard and show a number of important data points related to my training at the gym. I can see the weekly volume going up and down in the first image. This reflects exactly how much work I'm doing per workout and I should see it going up slowly over time. That same image also shows my TRAC scores, which monitor stress over time and ideally those should be in the green area most of the time. If stress creeps up into the red, the my training volume will need to be reduced so that I am not carrying so much fatigue. Finally, that image also shows my latest PR's or personal records. I can easily see which exercises I've improved on and which I have not. If I am going too many workouts without new PR's, then something will need to be adjust to continue progress. The second image shows my training calendar with Tuesday's specific workout enlarged and one of the exercises opened to reveal the actual weights, reps, and sets. This is how I actually record and plan what I'm doing day to day, week to week, and month to month. If it all seems complicated, know that I pay a coach to do this for me and so I don't actually think about any of this. I just open my workouts and do them. I can look at all the stats because they interest me, but it's really up to my coach to monitor it all and keep me moving forward. I just focus on having fun and lifting the bar. Lastly, I do keep one eye on my page views and visitors for this site, which you can see immediately above. The Weebly phone app is actually better than the website because it gives me a little more information about weekly, monthly, quarterly, and yearly views. I generally try to keep the number of views going up by the year and don't really pay too much attention to the week to week changes. Of the data points I actually look at, this one is only somewhat important to me.

I know that if I am reading about 50 pages or more per day, I will read thousands of pages every year. I will be more knowledgeable next year than this year. I know that if my workout volume goes up over time, I will be stronger and have higher work capacity. I know that if my stress gets really high either subjectively or because the TRAC points tell me, then I won't feel very good and life won't be as fun. Lastly, if I'm stronger, smarter, and better off tomorrow or next year than today, I try to share it with others by writing on this website. So how do I read, exercise, and work consistently every week? I just pick relevant data points and keep track of them. Just seeing the data keeps me focused and often more motivated than not. I do it because I want to, but there's also a positive feedback loop to the whole thing because actually seeing things go up in a positive trend is itself very motivating. That's it. If my values changed and I suddenly thought there were activities more important than reading, writing, and exercising, I'd try to track them the best I could with some kind of tool, even if it was just a tick-box on my wall. However, for now, those are the things most important for me feeling good and the only things I consciously keep my eyes on and refuse to let slide in the long-run. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed