|

Why children differ in motivation to learn: Insights from over 13,000 twins from 6 countries

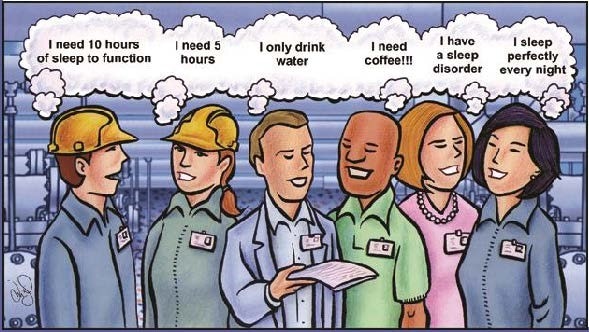

This study explored the etiology of individual differences in enjoyment and self-perceived ability for several school subjects in nearly 13,000 twins aged 9–16 from 6 countries. The results showed a striking consistency across ages, school subjects, and cultures. Contrary to common belief, enjoyment of learning and children’s perceptions of their competence were no less heritable than cognitive ability. Genetic factors explained approximately 40% of the variance and all of the observed twins’ similarity in academic motivation. Shared environmental factors, such as home or classroom, did not contribute to the twin’s similarity in academic motivation. Environmental influences stemmed entirely from individual specific experiences. Moreover, attending different classrooms did not increase dissimilarity between twins in their levels of enjoyment and self perception of competence. Equal similarity between twins attending same and different classrooms cannot be explained with equalising effect of the shared home environment as no such effect was found in this study. These results suggest that similarity in academic motivation for any unrelated individuals stems from their chance genetic similarity, as well as similar individual-specific environmental experiences, rather than similar family/classwide experiences. Whatever the environmental influences on the levels of enjoyment and self-perceived ability are, they seem to act in a non-shared, individual-specific way, potentially interacting with genetic make-up, experiences and perceptions. Multiple individual-specific life-events, such as birth complications, missing school due to illness, and peer-relations, may contribute to motivation. Effects of family members, teachers, classes, and schools may also be non-shared: parents, siblings, and teachers may actually treat children in the same family/class differently, responding to their individual characteristics (Babad, 1993; Harris & Morgan, 1991; Spengler, Gottschling, & Spinath, 2012). On the other hand, children may perceive their parents, teachers, classmates, and schools differently (Zhou, Lam, & Chang, 2012) – depending on other non-shared environmental and genetic effects. In addition, genetic effects may differ as a function of environment. For example, research suggested that heritability of reading might be moderated by teacher quality or SES status (Taylor, Roehrig, Hensler, Connor, & Schatschneider, 2010). True grit and genetics: Predicting academic achievement from personality. Twin analyses of Grit perseverance yielded a heritability estimate of 37% (20% for consistency of interest) and no evidence for shared environmental influence. Personality, primarily conscientiousness, predicts about 6% of the variance in GCSE grades, but Grit adds little to this prediction. Moreover, multivariate twin analyses showed that roughly two-thirds of the GCSE prediction is mediated genetically. Grit perseverance of effort and Big Five conscientiousness are to a large extent the same trait both phenotypically (r = 0.53) and genetically (genetic correlation = 0.86). We conclude that the etiology of Grit is highly similar to other personality traits, not only in showing substantial genetic influence but also in showing no influence of shared environmental factors. Personality significantly predicts academic achievement, but Grit adds little phenotypically or genetically to the prediction of academic achievement beyond traditional personality factors, especially conscientiousness. Understanding and Influencing Pupils' Choices as they Prepare to Leave School The data collected here suggests, simply, that pupils who like and admire their teachers perform better than students for whom this is not the case, and this is partly for environmental reasons. It is important to note that our study design does not allow us to identify the direction of effects and a positive teacher-pupil relationship could as easily be a consequence as a cause of high achievement. A related point is that Phase 3 analyses noted that pupils with relatively high g expressed higher average opinions of their teachers. This was particularly clear for Maths and Science. In summary, it remains unclear whether and how we can influence pupils’ choices and behaviour at this important developmental stage. However, our study has identified some key areas for discussion and further exploration. Given the prevalence of idiosyncratic experiences in our data we would also emphasise a need for ‘sensitive schooling’ in the form of personalisation and attention to individual differences. Great swathes of empirical data, including that presented here, suggests that all pupils are ‘special snowflakes’ who are likely to be helped (not harmed) by being recognised as such. Inequality in Human Capital and Endogenous Credit Constraints We find substantial evidence of life cycle credit constraints that affect human capital accumulation and inequality. The constrained fall into two groups: (a) the chronically poor with low initial endowments and abilities and low levels of acquired skills over the lifetime, and (b) the initially well-endowed persons with high levels of acquired skills. The first group has flat life cycle wage profiles. They remained constrained over most of their lifetimes. The second group has rising life cycle wage profiles. They are constrained only early on in life because they cannot immediately access their future earnings. As they age, their constraints are relaxed as they access their future earnings. Equalizing cognitive ability has dramatic effects on reducing inequality in education (Table 7). Equalizing non-cognitive ability has a similar strong impact. Earnings and consumptions, including family background, has much less dramatic effects after controlling for the other first order effects of cognitive ability. Reducing tuition substantially promotes schooling, but has only minor effects on our measures of inequality. Enhancing student loan limits has minor effects on all outcomes studied. There are dramatic effects of equalizing cognition but equalizing other factors What grades and achievement tests measure Cognitive skills predict life outcomes. This paper reinterprets the evidence on the relationship between cognitive skills and a variety of important life outcomes by analyzing the constituent components of widely used proxies for cognitive skills—grades and achievement tests. Measures of personality predict achievement test scores and grades above and beyond IQ scores. Analyses using scores on achievement tests and grades as proxies for IQ conflate the effects of IQ with the effects of personality. Both measures have greater predictive power than IQ and personality alone, because they embody extra dimensions of personality not captured by our measures. Why do these findings matter? Achievement tests are widely used to measure the traits required for success in school or life. It is important to know what they measure to design effective policy and use these measures to evaluate schools and teachers (evidence of teacher effectiveness on personality and its consequences for high school graduation is in ref. 28). Understanding the sources of differences in the test scores and grades used to explain the black–white achievement gap (29), the male–female wage gap (30), and other gaps by social class directs attention to what factors might be remediated (5). For example, personality or noncognitive skills are more malleable at later ages than IQ, and there are effective adolescent interventions that promote personality but are much less successful in boosting IQ (31, 32). The predictive power of grades shows the folly of throwing away the information contained in individual teacher assessments when predicting success in life. G Is for Genes Reading ability is distributed normally – a classic bell curve. That is, most people cluster around average ability, with a small proportion excelling and a small proportion struggling. Our ability to read is heavily influenced by our genes: estimates of heritability tend to hover between 60 and 80%. This means that a significant proportion of the differences between individuals in how well they can read can be explained by genetic influence, leaving as little as 20% to be explained by the environment in some studies (Kovas, Haworth, Dale, and Plomin, 2007; Wilcutt et al., 2010). Similar results have recently been reported from China, in spite of the very different orthography of Chinese (Chow et al., 2011). (p. 24) Is mathematical ability heritable? Yes it is. Kovas estimated the heritability of mathematical ability among 10-year-old children, as rated by their teachers, as about two-thirds. Shared environment accounted for 12% of the ability differences between children, and nonshared environment accounted for 24%. She had carried out a similar analysis when the TEDS twins were 7 years old and reached a very similar conclusion: teacher-assessed mathematics achievement was 68% heritable, with shared environment accounting for 9% and nonshared environment 22% of the differences between children. Similar results also emerged when the children were 9 years old. In this sample at least, which is representative of the wider UK population, a heritability estimate of 60 to 70% appears to be robust throughout the early school years. This mirrors our results for reading and writing. This is what primary school teachers are dealing with. Genetic differences at this stage are more important to mathematics achievement than differences in family income, family Monopoly or Rummikub sessions, parental education, gender, or school quality. Yet teacher training does not take them into account. In one sense, a heritability estimate of 60 to 70% tells the teacher nothing at all about what is possible, or even to be expected, from any particular child, but it should confirm that, for partly biological reasons, all of the children in her class are starting from different points and therefore need to take different next steps to develop their understanding and their ability. It should tell her that her job is to gradually draw out each child's potential rather than aiming, as a class, at some arbitrary, externally imposed target. Teachers already know this, but their methods are too often challenged by a political will to defy nature. Some kids start with a biological advantage in mathematics. It is not unreasonable to propose that those kids will develop differently from those who do not share their advantage. Is it unreasonable for education to reflect this? (pp. 44-45) So, by the end of our study we were left with the hypotheses that positivity about school, “flow” in the classroom, and peer stress, work as nonshared environmental influences on achievement. We also saw significant relationships between peer and academic stress and “flow”; and, in some subjects at least, between “flow” and academic achievement, which suggests a possible chain-reaction. We also saw that stress was negatively associated with “flow,” suggesting the hypothesis that classroom stress is linked to low morale and that this low morale, in terms of “flow” and positivity, has a negative knock-on effect on academic achievement. Perhaps there would be merit in teaching children how to handle stress and achieve “flow” as a means of boosting their academic performance? (p. 122)

2 Comments

I just binged watched Netflix’s show 13 Reasons Why and then read through the following: What Went Wrong With 13 Reasons Why? Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide Recommendations for Blogging on Suicide "13 Reasons Why" Netflix Series: Considerations for Educators NIH Suicide Statistics The Six Reasons People Attempt Suicide Causes of Depression What continues to jump out at me is that every criticism comes off completely flaccid. First, it’s fiction, which appears to have no strong empirical link to an uptake in suicide rates. That is not true for TV news coverage and celebrity suicides, according to the same article. There simply doesn’t seem to be much of a clear link with fiction and real life tragedy, although we can obviously find exceptions. Second, so what? None of the links above and none of the past readings I’ve looked at actually gives a good reason against suicide. It is labeled as a public health issue (unclear as to why) and is described as abnormal, but what does that mean? Obesity is a public health issue, but becoming more and more normal statistically. It’s fairly safe to say that being overweight or obese is statistically normal now. That’s the problem with using statistics. As abnormalities and deviations become more prevalent, they become more normal by definition. Does that mean public health concerns disappear when the issues become the norm? Is this statistical or definitional? Vox writes, That isn’t to say that everyone who sees 13 Reasons Why will be compelled to kill themselves, or even that a large percentage of the audience will. “It’s not that 50 percent of the people who see a depiction of suicide will be inclined to act,” Schwartz says. “But when you think about media that’s being consumed by large numbers of people, it will have an effect on a few of them, and when you’re talking about a life-and-death effect. … It’s small statistically, but it’s obviously desperately significant.” These types of statements can be applied to almost anything. Homicide, terrorism, war, eating bad food, driving drunk, reckless driving, etc. Car accidents accounted for 38,300 deaths in 2015. Suicides accounted for 44,193 deaths in 2015 according the NIH listed above. According to the same data, “1.4 million adults aged 18 or older attempted suicide” in 2015 and, “4.4 million were seriously injured” in car accidents. Where is the outrage? The trigger warnings? The public health expert outcry? Those numbers are for the US, but cars become much more dangerous once we move to global numbers where total deaths outstrip suicide by 425,000. If we wanted to be consistent, we should have the same types of articles and warnings for The Fast and the Furious as we do for 13 Reasons Why and ask the same question as the Vox article above. Imagine reading an article that read, For someone who is not struggling with reckless driving, The Fast and the Furious racing scenes are likely to be very moving. It will probably make them want to be more cautious drivers and help keep their friends from driving themselves. But for someone who is struggling with the “need for speed” thoughts, The Fast and the Furious could very well be a factor that leads toward their death. It would be ridiculous, though not because the problem is any less severe. Unintentional injury is the number one cause of death for persons aged 10-44. Driving is the biggest issue in that category. For ages 5-19, those deaths are most likely to be as passengers and not while behind the wheel themselves. It would make sense to see more outrage over other inflicted death via cars than self inflicted death due to suicide if the issue really were about death itself. I don’t think that’s the real issue, though. I think the real issue is that people feel guilt when they are near to a suicide. We like causes, responsibility, and blame to be clear. In most deaths, we can clearly point to those things. With suicide, we often have a need to turn the mirror inward and reflect on ourselves and what we did or didn’t do. That process is neither comfortable nor comforting in many cases. 13 Reasons Why doesn’t need any why of its own. It isn’t responsible for more suicides, at least no more so than the glamorization of fast driving, war, or other serious risks depicted in works of fiction. Looking at a TV show as a cause misses the point. So does a focus on suicide prevention. Preventing suicide in no way gets at a root cause, a reason to actually live. Preventing a negative doesn’t magically make a positive appear. If people are depressed and prevented the option of suicide with no legitimate or valid reasons for valuing life and looking forward to the future, it merely seems like a cruel joke. Society handles this terribly, and every time I ask for an answer I receive no reply. You don’t like suicide? Come up with a legitimate reason a person shouldn’t. Period. Until you do, I don’t want to hear about why it’s bad, wrong, weak, or should be stopped or prevented. It’s not enough to say, “Don’t do that.” The onus is on you to also say, “Because this alternative is so much better and worthwhile.” Suicide isn’t bad. Living in deep, persistent suffering is. Fix the suffering. The character Clay Jensen captures this succinctly when he tells the school counselor, It has to get better. The way we treat each and look out for each other. It has to get better somehow. I agree.

I've been reading more and more on the effects of schooling after posting What Does School Do Anyway? a few weeks ago. I continue to try and sort out the effects of schooling in terms of potential increases in variables such as cognitive versus non-cognitive skills, as well as income in order to understand where the biggest marginal impact of schooling comes from.

It seems more and more likely that schooling has a potentially larger effect on non-cognitive skills like self-control and physical health, than it does on dimensions like intelligence, critical thinking, or future income. Below are passages I've found to be helpful in recognizing some of these differences with hyperlinks to the books or articles. I'll try to update the information I'm looking at as I continue. The Marshmallow Test* In short, we are less likely to delay gratification when we feel sad or bad. Compared with happier people, those who are chronically prone to negative emotions and depression also tend to prefer immediate but less desirable rewards over delayed, more valued rewards. (p. 35) Prolonged stress impairs the PFC, which is essential not only for waiting for marshmallows but also for things like surviving high school, holding down a job, pursuing an advanced degree, navigating office politics, avoiding depression, preserving relationships, and refraining from decisions that seem intuitively right but on closer examination are really stupid. (pp. 49-50) *I haven't finished reading this yet. Giving Kids a Fair Chance GED test scores and the test scores of persons who graduate high school but do not go on to college are comparable. Yet GEDs earn at the rate of high school dropouts. GEDs are as “smart” as ordinary high school graduates, yet they lack non-cognitive skills. GEDs quit their jobs at much greater rates than ordinary high school graduates; their divorce rates are higher, too. 3 Most branches of the U.S. military recognize these differences in their recruiting strategies. GEDs attrite from the military at much higher rates than ordinary high school graduates. Cognitive and non-cognitive skills are equally predictive of many social outcomes: a 1 percent increase in either type of ability has roughly equal effects on outcomes across the full distribution of abilities. People with low levels of cognitive and non-cognitive skills are much more likely to be incarcerated. An increase in either cognitive or non-cognitive skills equally reduces the probability of teenage pregnancy. For the lowest deciles, the drop off in incarceration with increasing non-cognitive ability is greater than with increasing cognitive ability. We find similar patterns correlating both kinds of skills to high school and college graduation, daily smoking, and lifetime earnings. (pp. 12-13). The gaps in cognitive achievement by level of maternal education that we observe at age eighteen— powerful predictors of who goes to college and who does not— are mostly present at age six, when children enter school. Schooling— unequal as it is in America— plays only a minor role in alleviating or creating test score gaps. A similar pattern appears for socio-emotional skills. One measure of the development of these skills is the “anti-social score”— a measure of behavior problems. Once more, gaps open up early and persist. Again, unequal schools do not account for much of this pattern. (p. 14) A large body of evidence suggests that a major determinant of child disadvantage is the quality of the nurturing environment rather than just the financial resources available or the presence or absence of parents. For example, a 1995 study of 42 families by Betty Hart and Todd Risley showed that children growing up in professional families heard an average of 2,153 words per hour, while children in working-class families heard an average of 1,251 words per hour, and children in welfare-recipient families heard an average of 616 words per hour. Correspondingly, they found that at age three, children in the professional families had roughly 1,100-word vocabularies, in contrast with 750 words for children from working-class families, and 500 words for children of welfare recipients. (pp. 24-25) Programs that build character and motivation, and do not focus exclusively on cognition, appear to be the most effective. (p. 35) A growing body of evidence does suggest that cognitive skills are established early in life and that boosting raw IQ and problem-solving ability in the teenage years is much harder than doing so when children are young. But social and personality skills are another story. They are malleable into the early twenties, although early formation of these skills is still the best policy because they boost learning. Adolescent strategies should boost motivation, personality, and social skills through mentoring and workplace-based education. (pp. 37-38) The scarce resource is love and parenting— not money. (p. 41) The replication was called the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP). It had a randomly selected treatment group of 377 and a control group of 608, all of them low– birth weight babies. For each infant the intervention began upon discharge from the neonatal nursery and continued until the child reached 36 months of age. The program had three components: frequent home visits by a trained counselor, attendance at a child development center five days a week for at least four hours beginning at twelve months, and parent group meetings after the children reached twelve months. The intervention was designed on the Abecedarian model and in many ways was more intensive. The first follow-ups at 24 and 36 months were highly positive. By the time the participants were age five, however, most of those results had disappeared. In the follow-up at age eighteen, the results for the treatment and control children showed no effect for any of the indicators, which covered intellectual ability, academic achievement, behavioral problems, and physical health. (pp. 64-65) the experience of early childhood intervention programs follows the familiar, discouraging pattern that led him to formulate his laws: small-scale experimental efforts staffed by highly motivated people show effects. When they are subject to well-designed large-scale replications, those promising signs attenuate and often evaporate altogether. (p. 68) Head Start is the federal government’s primary early childhood program, with a budget of almost $ 8 billion. According to its most recent assessment by the Department of Health and Human Services, it has almost no lasting, positive cognitive effects, and its few, persisting social-emotional impacts are mixed positive and negative. It also suffers from widespread management problems, with federal officials struggling to keep tabs on providers and hesitant to dock poor performers. What seems to have kept it alive is advocacy by providers and widespread support for its mission. California’s class-size reduction illustrates the huge constraints on taking resource-intensive programs to scale. Inspired by the successful Tennessee STAR experiment, California undertook statewide class-size reduction in the 1990s. The effort failed, producing no conclusive achievement gains while creating a major shortage of qualified teachers. California simply couldn’t staff all the new rooms. (pp. 86-87) Cognitive skills solidify by age eleven or so. For them, early development is important. Personality is malleable until the mid-twenties. This is a consequence of the slowly developing prefrontal cortex that regulates judgment and decision-making. These fundamental biological and psychological facts explain why successful remediation strategies for adolescents focus on improving personality skills. I cite evidence from effective early intervention programs with 30 or more years of follow-up. They have been rigorously evaluated and show benefit-cost ratios and rates of return that compete with those of stock market investments in normal years. All of the respondents agree that the early years are important and that families play important roles in shaping the child. Lelac Almagor and Carol Dweck note that it would be helpful to parse out which features of the successful interventions lead to success— to “go into the black box” of program treatment effects. I agree. My colleagues and I have done so by establishing that the substantial effects of the Perry program are due to improvements in the personality traits of the participants. The next generation of intervention studies needs to move beyond reporting treatment effects in order to understand the precise interventions that produce the measured effects and the mechanisms through which they operate. (pp. 126-127) Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses A notable finding emerges with respect to the amount of time students spend studying (see table A4.2 in methodological appendix). There is a positive association between learning and time spent studying alone, but a negative association between learning and time spent studying with peers. (Kindle Locations 2032-2034) What students bring to college matters; this is particularly the case with respect to their academic preparation (SAT/ACT performance, number APs, HS GPA). (Kindle Locations 2349-2350) when faculty have high expectations and expect students to read and write reasonable amounts, students learn more. In addition, when students report that they have taken a class in which they had to read more than forty pages a week and write more than twenty pages over the course of a semester, they also report spending more time studying: more than two additional hours per week than students who do not have to meet such requirements.67 Thus, requiring that students attend to their class work has the potential to shape their actions in ways that are conducive to their intellectual development. (Kindle Locations 2362-2367) The final analysis—which includes all background measures, college experiences, and institutions attended— explains 42 percent of the variation in CLA scores. This is a substantial amount by social science standards, although it does imply that much more research is needed to understand the remaining variance. Within our analyses, college experiences and institutions attended explained an additional 6 percent of the variance, after controlling for academic preparation and other individual characteristics.68 While that may appear to be a small contribution, academic preparation, which has received much attention in research and policy circles, explains only an additional 8 percent of the variance beyond students’ background characteristics.69 These estimates may seem low, but this is because of our analytic strategy: we are focusing on growth and are thus controlling for 2005 CLA scores, which, as would be expected, explain the largest portion of the variance in 2007 CLA performance. Thus, students’ college experiences and institutions attended make almost as much of a difference as prior academic preparation. If the blame for low levels of critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing skills of college students is to be placed on academic preparation, then almost an equal amount of responsibility rests with what happens after students enter higher education. (Kindle Locations 2370-2381) Returns to Education: The Causal Effects of Education on Earnings, Health and Smoking Graduating high school benefits all—and especially low-ability persons. Only high-ability individuals receive substantial benefits from college graduation. Higher ability is associated with higher earnings and more schooling. However, as shown by the grey bars in Figure 2, adjusting for family background and adolescent measures of ability attenuates, but does not eliminate, the estimated least squares estimates of the effects of education. Disaggregating by ability, the effects are strong for high-ability people who enroll in college. They are especially strong for those who graduate college. We find little to no evidence of any benefit of graduating college for low-ability individuals.77 In fact, the point estimates are negative, albeit imprecisely estimated. Although there are wage rate benefits to low-ability people for enrolling in college (Figure 4A), the benefits in terms of the log present value of wages are minimal. For these people, the wage benefits of attending college barely offset the lost work experience and earnings from attending school. Our findings thus support the basic insights of Becker (1964). Schooling has strong causal effects on market and non-market outcomes. Both cognitive and non-cognitive endowments affect schooling choices and outcomes. People sort into schooling based on realized incremental gains. The Labor Market Returns to Cognitive and Noncognitive Ability: Evidence from the Swedish Enlistment We find strong evidence that men who fare poorly in the labor market—in the sense of unemployment or low annual earnings—lack noncognitive rather than cognitive ability. However, cognitive ability is a stronger predictor of wages for skilled workers and of earnings above the median. cognitive ability is a much stronger predictor of higher education than noncognitive ability. For example, cognitive ability is an almost four times stronger predictor of a university degree than noncognitive ability Understanding household financial distress: The role of noncognitive abilities Character skills are part genetics and part the influence of early childhood experience. In adulthood, these skills are hard to change. Using panel data, we find that a person's noncognitive skills are highly correlated over time. More research, however, should be devoted to whether traumatic events can alter a person’s abilities, either in the short run or even permanently. Also targeting young children to design educational programs that develop noncognitive abilities would be highly cost-effective. Recent research shows the return on investment in education from birth to age five is 13% (Garcia et al. 2016). High-quality education should not only foster cognitive skills, such as the ability to acquire and retain knowledge (Heckman et al. 2013, Cunha et al. 2010). Character – perseverance, motivation, self-esteem, emotional stability, and conscientiousness – is important too, as this research has shown. Improved noncognitive abilities will greatly influence financial wellbeing, income, education, and health throughout the life of an individual. Rethinking education, work and ‘employability’ However, human capital theory fails the test of realism, truncating possible knowledge about education and work, because of weaknesses in its meta-method: theorisation using a single lens, closed system modeling of social relations, the application of mathematical tools to inappropriate materials, and the multivariate analysis of interdependent variables. These weaknesses lead to numerous lacunae. For example human capital theory cannot explain status objectives, which are more important for some graduates, and in some countries, than others; or how education augments productivity; or why top-end salary inequality has increased dramatically in some countries. The limitations of human capital theory are discussed with reference to research on social stratification, work, earnings and education.

Mark Watney: At some point, everything's gonna go south on you... everything's going to go south and you're going to say, this is it. This is how I end. Now you can either accept that, or you can get to work. That's all it is. You just begin. You do the math. You solve one problem... and you solve the next one... and then the next. And If you solve enough problems, you get to come home. All right, questions? I watched The Martian for the second time this past weekend and I’ve been thinking about the above quote since. It seems to capture much of what life and existence is - a series of problems. We can accept problems as they arise and live with them or we can begin working to solve them.

Regardless of how many we choose to work on and possibly solve along the way, more will pop up. Life is problems, sequentially encountered, often in parallel, until we die. Framing it this way has actually been really nice for coping with that reality because it highlights the futility of working on all problems, all the time. Instead, I can simply focus on the problems that are meaningful to me and that I would feel satisfied with advancing solutions to and accept the rest, which will hopefully be picked up and solved by others. We call all of this collective problem solving “progress”. I think the central problem I can most contribute a partial solution to is student suffering and wasted potential from the systemic issues with modern schooling. That’s an endless problem, but I can chip away at it with each student I encounter. There are many other problems that concern me greatly: absolute and relative poverty, health and healthcare, equality of rights. However, those seem beyond my maximal effective impact. I enjoy highlighting them as potential problems that some of my students may wish to take up in the future, but I am better equipped to help them than I am to reduce poverty, disease, or legal protections for oppressed groups of people. I also am not sure that my best personal fit will be in classroom teaching. I think classrooms are some of the major contributors to the student suffering and wasted potential I mentioned above. I am still figuring out how to chip away at the problem. I know from experience, I’ve felt most successful in one-on-one tutoring or adult education. Perhaps I will return to those or something else entirely. I recently had a long talk about what I perceive to be the mental health community’s ongoing failure. They simply aren’t being very successful in terms of meaningful impact on the problem of depression from the evidence I’ve seen. I’m clearly not an expert in this field, but any reasonably educated person can read through research reviews and summaries and draw at least a few conclusions.

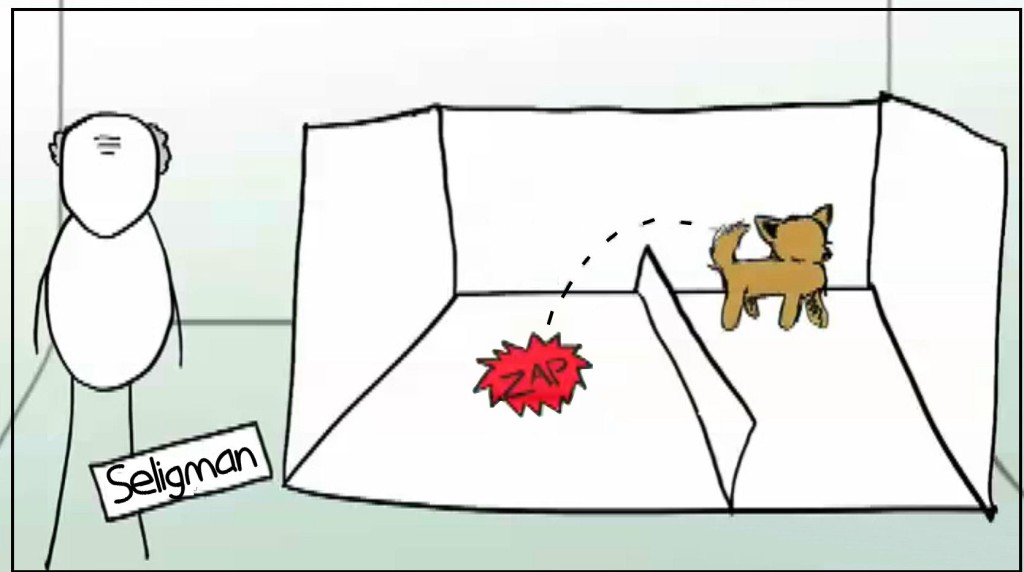

First, the economic burden of depression is increasing. I imagine at least some of that is from a profit motive as depression becomes ever more clinicalized. Second, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the US. Third, the rate of suicide has surged dramatically over the past 30 years, increasing by 24 percent overall since 1999. Fourth, the average age of onset for depression has decreased from 29.5 to between 14 and 15, while also seeing rates increase between 10 and 20 times in the same 30 year period. Fifth, these numbers for depression affect about seven percent of the total population in the US and people are 50 percent likely to relapse after the first episode. Sixth, depression affects 300 million globally and suicide is the second(!!) leading cause of death for ages 15-29. Seventh, these issues are largely considered the result of modernity. When I see depression and suicide going up, with higher economic burdens over time, and that relapse is very likely to happen, then I conclude the mental health community is largely ineffective at the moment. The direction these numbers are moving is not the direction we want. I don’t hold them responsible for this or think they aren’t doing their best. The numbers just suggest a certain, very specific, reality despite their efforts. I also recently wrote an article titled School Is Ruining Society. After talking about the above for over an hour with a colleague and reflecting on it even more post-dialog, it seems to me there is an argument to be made that connects the rates of depression cum suicide and the ideas discussed in my article on the failure of school. That connection is that school teachers learned helplessness and that results in many of the issues we are seeing today. What is learned helplessness? “Learned helplessness is the belief that our own behavior does not influence what happens next, that is, behavior does not control outcomes or results.” For a book length understanding, see Christopher Peterson’s book. Now think about school. Does any student’s behavior influence what happens next in a genuine way? Does their behavior control the outcomes and results that matter to them? Sure, if they study harder, they can learn their behavior partially controls their test results. That seems a limp victory though. Does their behavior give them any control over the actual subjects, topics, concepts, or skills they learn? Does their behavior control their schedule, room, seat, or surrounding peers? Do they have any control over the tests, scoring, rubrics? What about actual physical action? Do they control when they get to sit, stand, exercise, design or create projects? The answer to all of these questions seems obvious to me. Remember the average age of the onset of depression above - between 14 and 15? That is roughly when students start entering high school. It’s also the average, so some will experience the onset earlier in middle school. That is roughly the same time that students are likely becoming ever more conscious that their behavior has little impact on the outcomes and results important to them. Before that time, young children are often highly interested in receiving approval and praise from adults and so throughout much of elementary school a student’s behavior does have some direct impact on the outcomes meaningful to them. I don’t know if teaching and focusing on learned optimism, the opposite of learned helplessness, as "a" or "the" primary aim of schooling throughout the middle and high school years would fix all of these issues. Obviously our environments are made up of many factors beyond school. However, I suspect learned optimism is one of the primary mechanisms behind a variety of other interventions popular in education. Think about the ideas of “growth mindset”, “grit”, and “deliberate practice”. A growth mindset occurs when individuals believe their talents can be developed (through hard work, good strategies, and input from others). Grit is defined as the “tendency to pursue long-term challenging goals with perseverance and passion”. It is largely mediated by deliberate practice, which “involves stepping outside your comfort zone and trying activities beyond your current abilities. While repeating a skill you’ve already mastered might be satisfying, it’s not enough to help you get better. Moreover, simply wanting to improve isn’t enough — people also need well-defined goals and the help of a teacher who makes a plan for achieving them.” To the extent the above three ideas are absorbed by students, they learn that their behaviors affect outcomes - the opposite of learned helplessness. They are also all highly correlated with positive life outcomes or what we might generally call “success”. If teachers can flock to and adopt these ideas so readily, could we not also dive a little deeper and take notice when class activities may be leading down the wrong path of learned helplessness? I would argue most other learning in school is of secondary importance. Math ability or reading ability is of little importance if students also leave school depressed and suicidal. What’s happening now isn’t working. We can’t continue living in a society where our youth are learning their actions don’t matter and not prepare them with skills to affect change. Students deserve to both learn and know, deep in their bones, that their behavior and desired outcomes matter to us adults and that we can and will help them to actualize their interests and goals. I've recently had a student email about ten times regarding material completely independent of class. In fact, I don't even teach the student in one of my own classes. They just happen to know I like the topics they're interested in. I've been pretty direct in poking holes in their thinking and pointing out what I consider to be errors or lapses in understanding. At the same time, I couldn't be more impressed by the intellectual charge they bring to the conversations and the genuine, obvious passion displayed for testing out beliefs to see how they hold up. In order to not focus solely on breaking down their beliefs and understandings, I wrote them the email below. I feel it's probably good for any student to read. Teachers aren't all knowing and we rarely know much about what's important to the students themselves. They deserve to know that and be reminded as frequently as possible. We have to learn things just like them and that requires chasing down and tackling new knowledge and understanding actively and vigorously. Waiting for it in class is a non-starter. It may never come. Hi, Good teachers don’t exist.

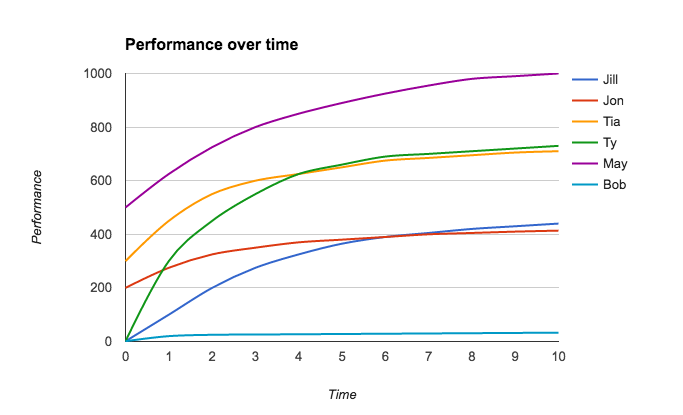

At least not in a meaningful way. This is largely semantic, but think about what would make a teacher a “good” teacher. How do you provide evidence that someone is a good teacher? One place to start would be with asking stakeholders. Which stakeholders matter in deciding it? School districts? Administration? Fellow teachers? Parents? Students? The teacher his or herself? All of the above? All of the above would be too high a standard as no one would be a good teacher if all the stakeholders had to agree completely. So perhaps some percentage of the stakeholders? Is a simple majority of 51% enough? What if 90% of the administration, fellow teachers, and parents believe a person is a good teacher, but zero percent of the students do? Does the teacher still count as a good teacher? What if 100% of the students feel someone is a good teacher, but none of the adult stakeholders do? This can get more complicated by a further step. What if all the stakeholders mentioned above agree someone is a good teacher using 51% as the percentage threshold in one location, but not another? If all stakeholders in a public, San Diego, suburban high school agree a person is a good teacher and he or she moves to a private, Beijing, urban high school and none of the stakeholders believe he or she is a good teacher, who is right? Is this another question of percentages? Do we need 51% of locales around the world to agree a person is a good teacher? The above is premised on stakeholders having some kind of final say, but is that reasonable? Perhaps total societal welfare is a better metric. What if all the stakeholders mentioned above believed a person was not a good teacher, but total welfare in society actually goes up because of the person’s teaching? This might be seen in an example where a teacher focuses on creativity and innovation to the detriment of time spent on the standard curriculum. Perhaps the teacher is even fired for neglecting pre-written standards regarding math and language, but winds up sparking the next Facebook or Apple CEO. Would that teacher be a good teacher even though no one else recognizes them as such and actually lays them off? All of the above conflicting goals and agendas makes it impossible to state categorically if a person is a good teacher. I have found that generally speaking, being a good teacher is simply a process of doing what one is told by administration while trying to make parents and students feel good. In terms of achieving a job description, that seems to work. Since that job description changes at each school, it looks different everywhere you go. Am I good teacher? I can’t tell you that. The strongest claim I can make is that I’ve never been fired or had any major problems. I don’t think my students hate me or my class, but maybe they’re just better poker players than I am. Some are definitely bored, but I would be too if I were forced to take an art class for example. It’s just not my cup of tea. To each their own. Can I teach a particular subject well, say math or economics? That depends too. If you are interested, then sure. If you aren’t, it probably doesn’t matter. That differs from tutoring where essentially every student is “interested” in that they personally pay me and take the time to show up and listen. In a room of students, that isn’t the case. Some will listen and want to learn, others will look like they are, but aren’t, and still others will actively disengage altogether. I have the impression that teachers tend to have an overinflated sense of themselves. I would argue there are very few good teachers, based on metrics that matter to me, but most teachers probably feel they are pretty good or above average. It’s the Lake Wobegon effect popping up. In reality, most teachers could be replaced by the average caring adult and not be missed at all. The marginal effect of any one teacher is almost zero. I’d say it’s much more important to weed out potential problems from teaching than anything else. It’s much clearer that we can have truly bad teachers, ones that damage and harm students either physically or emotionally. The marginal effect in those cases is very high and very negative. It’s much less clear going the other direction. So give me your thoughts. What makes a good teacher? Is it universalizable or always specifically context dependent? Is there any meaningful sense to the phrase? Above are six learning curves representing six hypothetical persons. You can see a variety of initial performance levels, going from 1 for Ty, Jill, and Bob at time 0, all the way up to 500 for May. You can also see a variety of ending performance levels, going from 33 at time 10 for Bob, all the way up to 1000 for May. All of the learning curves on the diagram above improve over time, as represented by increased performance over time and all have different rates of improvement over time. The question I want to answer is, “Can all students can learn?” It depends. In the above learning curves, all students show improvement. However, that means almost nothing given the different rates of improvement and absolute performance levels over different time periods. In fact, the idea that growth rates or proficiency levels (performance levels) tell us anything at all is patently absurd once the above curves sink in. Let’s start by measuring some growth rates. Bob (light blue curve) went from a performance level of 1 to a performance level of 33. Bob’s percentage change = (33-1/1) x 100 = 3200% We could also state that Bob is 33 times “better” at time 10 than he is at time 0. Either way, that’s a lot of improvement if we compare it to May (purple curve). May’s percentage change = (1000-500/500) x 100 = 100% We could also state that May is 2 times “better” than when she started. Clearly Bob has much more “growth” than May if we use simple percentage change formulas to find a growth rate. However, if we switch from growth rates to proficiency levels as measured by the absolute performance levels, we find that May is 30.3 times (1000/33) “better” than Bob. If we had a school initiative that made sure certain minimums were met, should it measure those minimums using growth rates or proficiency levels? If we set the minimums using growth rate targets at 500%, May (100%) is falling behind, but Bob (3200%) is doing great! He meets the minimum after time 1, whereas May never reaches the target. If we set minimums using proficiency levels and use a performance level of 400, then May (500) meets the target at time 0, while Bob (33) is still 377 points shy at time 10. If we look at the other people in the diagram above while using the same targets, either 500% growth or a 400 proficiency level, we run into similar problems. Tia never reaches the growth target, but does cross the 400 target by time 1. Ty crushes the growth target and also meets the proficiency target by time 2. Jon never reaches the growth target, but reaches the proficiency target after time 7. Jill meets the growth target easily, but takes until time 7 to reach the 400 proficiency target and we can easily imagine her curve never crossing the proficiency threshold by simply shifting it down a bit. The above presents serious problems for standards-based initiatives like the hypothetical one above. A number of students will be measured as falling behind depending on how we select our targets. Furthermore, even if we agree to the target, there is the pesky question of time allowed to meet it. If the target is set at a 400 proficiency level, but it is expected to be met by time 1, only Tia and May will reach it. If we allow until time 6, we can add Ty. If we extend it to time 7, we include Jill and Jon. Many schools, districts, and nations use metrics similar to the above for measuring student learning. The United States has No Child Left Behind, but is by no means the only one to measure student learning with some type of standards. It began under a proficiency model of measuring absolute performance, but has since begun shifting to growth models in several states. The OECD has PISA. The International Baccalaureate uses proficiency levels with its standards-based rubrics. It should be clear that both growth and proficiency metrics have inherent problems. The above is aimed at showing how absurd many student measurements of learning can be. Success and failure are totally dependent on the metrics we decide to use. That only becomes worse the more variables we measure. For example, let’s assume the above learning curves are for math. What happens when we add language and find students with language learning curves that don’t match their math learning curves. Perhaps, Bob and May are completely reversed and we find May with low absolute performance levels and Bob with high absolute performance levels. Do they both count as failing if we require a proficiency level of 400 for both math and language? I recently finished Why School?, by Will Richardson, who stated the following in his book’s final pages, I can’t wait 10 to 20 years. By that time, our kids will have long since graduated, and the story of what schools become will have already been written. I hope they are places where adults and children come together to learn about the world, places rich with technology that lets our kids dream big and create things to fuel those dreams. I hope schools will be places where learning is fun, where it’s not so much about competing against one another as about working together to solve the really big problems we’ll face together in the years ahead. (Kindle Locations 559-562) That seems right to me.

Let’s return to the initial question, “Can all students learn?” Of course, but what that means is up for debate. If it means hitting a particular standardized level of proficiency or growth, then no. Some students will never reach particular growth or performance levels selected for them. However, if, as Richardson writes elsewhere in his book, it means that students, "have the skills and dispositions they need to solve whatever hard problems come their way, and [that] they’ll know how to go about creating something of value and sharing it with the world,” then YES! (Kindle Locations 543-544).

|

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed