|

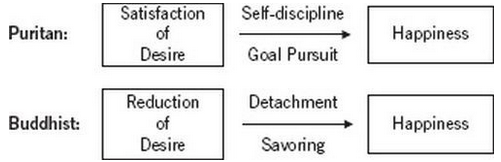

Running hard is painful. So is lifting weights intensely. You can often feel a sort of panic brought on by the shortness of breath, elevated heart rate, and deep burning in your lungs or muscle tissue. However, for most people who undergo this willingly, these activities induce no suffering. That’s because suffering is a psychological state and not connected necessarily to a physical state of pain. We can recognize that the pain from exercise will potentially lead to us achieving our desired goals and end states and therefore not suffer at all, but actually revel in it. Understanding suffering in this way allows us to see that most suffering is generated by desire. This can be overcome in a couple of ways. The above diagram comes from the textbook The Psychology of Desire1 and is a comprehensive handbook on the state of desire research. It’s also pretty handy for understanding our options when it comes to suffering. We can satisfy our desire through hard work and effort over time, which leads to a sense of satisfaction, accomplishment, and well-being. Or, we can reduce and eliminate our desire by detaching ourselves from it and thus being able to enter into a state of contented happiness or well-being where there is no frustration or anger at our inability to achieve our own ends. The Life of a Hermit Looking at the second choice, it seems clear to me that the ascetic life is the most pure instantiation of this way of achieving well-being. The more detached you become, the less need you have for interacting with the world. Detach from enough desires and you are left with little reason to chase development or improvement. This is not a critique of this choice. Simply a logical consequence. A large benefit is that if everyone chose this lifestyle, we would have no violence or war. As a species we would not wish to covet the material objects of others or even relationships with other people. It is difficult to fight violently over anything when you do not desire a loving relationship with another person or a particular material object. The cost is that we become completely subject to the world around us. Lack of food and shelter with a prevalence of disease can easily cripple, maim, or kill us. Most of us will experience suffering because of these things and it seems to be quite the undertaking to truly separate our evolutionary psychology from desiring not to experience these painful aspects of a life devoid of material benefits. While it is difficult to imagine doing this, it’s not impossible. I can certainly imagine a state of existence where hunger, subjection to the elements, and disease or injury are simply recognized as painful stimuli, much like the exercise examples we began this discussion with. However, even upon recognizing these states of being as simply physical stimuli and not states that induce suffering, it is much harder still to imagine them as states that cause true happiness, well-being, or flourishing. This lack of imagination on my part is what turns me to the first option. Desire Satisfaction If we agree that desiring satisfaction isn’t the best path to well-being because of its inability to provide the things worth living for, we naturally turn in the other direction. Upon doing this, we must first ask what satisfied desires are most likely to lead to well-being. Philosophers, psychologists, and economists have thought, discussed, and written on this topic for centuries.2 Throughout this time, the problem has often felt intractable. However, contemporary thinkers appear to be making some headway. A few common answers include3:

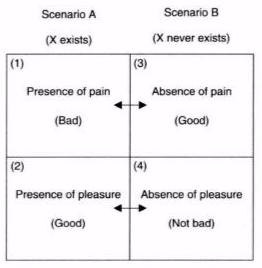

While I don’t see anything inherently negative in flow and it has been labeled as “peak experience”5, there is no requirement that flow involve other people and it can therefore be attained in meditation like the hermit lifestyle discussed above. It that sense, it isn’t necessarily much more than a neutral hedonistically pleasureable experience that leaves us with a sense of well-being and satisfaction at no one else’s expense. This really only becomes a problem when you introduce the last three things on the list above: accomplishment, purpose, and social connections. Accomplishment, Purpose, and Connection It is at this point that “others” clearly and aggressively enter the scene in the pursuit of happiness. Christopher Peterson has summarized the findings of positive psychology research as simply showing, “that other people matter in pursuit of the good life”.6 In addition, neuroscience supports the idea that our psychological machinery related to moral intuitions has developed for the sake of human cooperation.7 All of this points us in the direction of an ethical ideal based on caring8, well-being9, and the alleviation of suffering, both that of our own and others’. By setting our purpose in life as the pursuit of the good life, which relies fundamentally on others, we can judge how well we are doing by how well we are able to accomplish the increase and development of the well-being of others. And that’s the rub. Our existence inherently causes the suffering of others. It’s a real “damned if you do, damned if you don’t.” Your Existence Is Hurting Me I’m guessing most people reacted with surprise, rejection, or denial of the statement above and not an agreeing head nod. It warrants explanation. Some examples probably make this easier. Louis C.K. does a great job in the following clip. Perhaps something closer to home and not so distant? Louis C.K. does a better job than I ever could yet again. So even in the final analysis of what makes a good life good, we simply won’t be able to satisfy those desires as the diagram at the top of this post illustrated. If we aren’t able to satisfy our noblest of desires and eliminating them altogether seems to leave life neutral at best, what are we left with? One answer that has become more and more interesting to me is the answer that existence simply isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. In a wonderfully eloquent and well reasoned book, philosopher David Benatar deduces that existence is always a harm.10 He reaches this conclusion through some simple logical analysis of the asymmetry between pleasure and suffering in existing and not existing. It is the bottom right quadrant in the diagram above that grants not existing the asymmetrical advantage over existing since we can deduce that never existing beats out existing in regards to pain/suffering in the first row. The second row is what illustrates the fact that not existing means not experiencing pleasure, which is “not bad”, and that is different than the “bad” that we would need in order to preserve the symmetry.

If you have followed me to this point. It is my hope that you agree with me that the Buddhist solution of reducing or eliminating desires is not adequate. Neither is the Puritan solution of desire satisfaction. That leaves us in quite the bind. One that Benatar and the diagram above solves for us. So I am left asking this question: why is existence good? Further Reading

1 Comment

|

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed