|

Driverless taxis are here. I asked my 12th grade economics class yesterday what they would do when they couldn't grow up to be taxi drivers. They pretty much all laughed. That’s to be expected in a school where most students are children of very wealthy professionals. None of them imagine a future for themselves where driving a taxi is a legitimate choice.

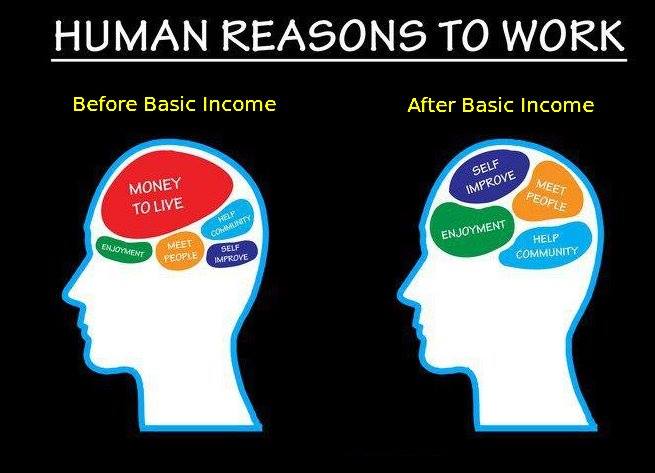

I then asked them what they would do for work when they grew up and couldn't work as accountants because programs like TurboTax begin to outperform all accountants except the best in the world, thereby replacing 99% of all future accountants. That got fewer laughs. Then I asked them what they'd do when IBM's supercomputer Watson, which famously beat all human competition at Jeopardy, was successfully reprogrammed to become the world's best doctor (something currently underway). They pretty much all stopped laughing at this point. One student, after about 10 seconds of reflection, answered very simply, "Give everyone an allowance." Bingo! If the industrial revolution replaced muscle power with machine power and the current computing power is replacing brain power and making most service-based knowledge work redundant, the only reasonable answer to come up with is a creation of a universal income. Several nations are already talking and beginning to experiment with that idea. I imagine it will take awhile for America to take it seriously though. Don't you think there will be new "occupations" created that we cannot comprehend today? Humans have muscle and brain power to work with. If you strip them of the ability to employ either of those, there are few occupations imaginable. One area, of course, would be in socio-emotional services - something computers are bad at - that don't necessarily require massive levels of muscle or brain power (of the logico-mathematical variety anyway). This would essentially mean teaching people to simply be kind and compassionate towards one another, but it’s hard to see it as an avenue for massive employment. This is essentially the realm that feminism has being attempting to legitimize for the past century, but without any luck in applying it toward paid services. Innovation is slowing down more generally and it takes more and more expertise, training, and schooling to reach the edge or frontier of complex fields like computer science where most technological breakthroughs happen. This greatly limits the number of people capable of contributing economically in terms of productivity through innovation. This isn't because of inequality either. Even if education were completely free at all levels, there simply aren't that many people capable of having insights at the level needed to create progress in the fields that generate prosperity, such as the STEM subjects. This is exaggerated by the "winner take all" system that has developed due to mass communication and transportation. The best in the world at accounting can now have a computer programmer create systems like TurboTax and then sell that product to everyone without being limited by geography. You already see this in fields like music and acting, where celebrity was once confined by geography to the number of people you could perform live in front of. Now, the best musicians and actors in the world can sell their products on iTunes and Amazon to the entire world. The same will be true of just about all service-based knowledge industries given enough time. Of course, something dramatic could happen that totally upends what we know of history and economics. Right now, we categorize economic output in only four major sectors: agricultural, industrial, service, and creation. Technology is eliminating the first three as secure employment sectors and that leaves us with only the fourth sector centered on creativity, which as pointed out above is essentially unreachable by most people even if they are endowed with unlimited financial backing and equal opportunity. New ideas are just really, really hard to generate. This is why socio-emotional education based on caring and compassion become even more important. We will almost certainly need "an allowance", what economists call a universal or basic income, as my student put it above for most people. This requires that the majority of the voting public agree to endorse policies that have social welfare and the great mass of people in mind. Our world is getting richer. Wealth is not the issue here. Technology allows us to produce more goods and services for a greater number of people, giving us more options, prosperity, and a higher quality of life overall. However, we currently believe that the inventors and innovators deserve to capture all of the rewards for themselves. This is just one viewpoint, not the only one. Another viewpoint is that we can choose to live in a society where we educate all, with the expectation and knowledge that only a small percentage will continue to create wealth through innovation, while at the same time requiring them to share that wealth once it is created. It only requires that we care enough to do it and stop believing that individuals deserve to keep whatever they create all for themselves. After all, they are able to create their innovations only because of the entire system that is in place: state infrastructure, state education, state laws, and state citizenship that leads to state protection. Instead of seeing people as rightful owners of wealth, we need to view them as stewards of wealth. If they are not stewarding wealth appropriately, meaning using it to make everyone better off, they are not entitled to it. This follows the same vein of thinking as the original idea of a social contract between the populace and government, only now it is extended to a social contract between the populace, the government, and the wealthy. We can make these changes civilly through education, legislation, and democratic consensus, or we can wait until movements like Occupy Wall Street go from non-violent demonstrations and protests to violent revolutions. The choice is ours.

2 Comments

People learn primarily through social interactions of one kind or another. We talk to people, we read, we listen and watch TV, movies, and the news. There really isn’t much variety to how people learn. We take in information in one form or another and that information has to come from somewhere.

Of course, it is possible that we learn by creating knowledge, either for ourselves without help or for the first time, but that is much more rare. That is essentially what academics do. They create knowledge through their research projects by analyzing, evaluating, and interpreting the data they collect, whether quantitative or qualitative. Assuming you aren’t an academic or some other knowledge creator, you probably learn from others through the methods mentioned above or possibly even direct imitation like a child or athlete does with their parents and coaches, respectively. This begs the essential question: Who should we get our information from? Who should we listen to, believe, and regard as valid deliverers of knowledge? Technical Knowledge The quality of technical knowledge comes in a huge variety of forms. Just like the quality of food we take in daily impacts our physical health and robustness, the quality of information and knowledge we absorb day to day impacts our intellectual health and robustness. Dilettantes and Charlatans One of the most important areas of knowledge in today’s world is technical knowledge. This is what we typically rely on experts to generate and disseminate and is considered the “bottleneck of all expertise”. Yet we often don’t get our knowledge from experts. One example of this is demonstrated by using Amazon to search through books on various topics, something I enjoy doing on a regular basis to try and notice what books have the most reviews, which authors have the highest sales ranks, and what books are topping the bestseller lists in different categories. For instance, Dan Harris, correspondent for ABC News and the co-anchor for the weekend edition of Good Morning America, has one of the most reviewed and top ranked books in the category of “happiness” on all of Amazon. It has over 2,200 reviews (an astounding number for Amazon) and as of this moment, ranks #9 on the bestseller list in this category. While happiness might be considered a field that is accessible to anyone with an opinion and open for advice from all parties, there is in fact an entire field of empirical, and therefore non-anecdotal, research devoted to the topic. You would think that anybody serious about learning about happiness would take the time to investigate the preeminent researchers in that field (positive psychology) and begin their reading and learning with them. This is not to say that non-researchers have nothing valuable to say, just that the validity is immediately questionable until proven otherwise. In continuing a search within the category of happiness by “most reviews” on Amazon, the very next page has a book titled The Happiness Advantage: The Seven Principles of Positive Psychology The Fuel Success and Performance at Work and is written by Shawn Anchor. This would appear to be a better start. After all, the title directly references the field of positive psychology that I just mentioned. His biography also includes working and lecturing at Harvard. Yet, if we dig a little deeper, we can find out that he worked as a dormitory Freshman Proctor at Harvard after receiving a master’s degree in divinity and helped lecture as a teaching assistant for a professor that taught a course on happiness. He is hardly the academic expert on the subject that first glance might convince us that he is. Mystics and Pop Expertise Continuing our search, we would stumble upon the The Art of Happiness a few pages deeper into the search results of Amazon. This has about 100 reviews less than Anchor’s book and about 1,500 reviews less than Harris’ book. It is co-written by the Dalai Lama and Howard Cutler, the spiritual and former state leader of the Tibetan people and a psychiatrist respectively. This is a much better starting place. The Dalai Lama has spent, quite literally, his entire life studying happiness through subjective introspection, argument, and experiential reflection. Cutler has a medical degree and has practiced for years as a psychiatrist, working with actual people who seek his help in becoming happier. If you don’t like the idea of getting advice from a professed spiritual leader (always a murky area that contains a lot of nonsense and supernatural mysticism), but do like the idea of an MD or PhD who has spent their entire life rigorously studying the subject then the search would have to continue even further. To get away from dilettantes like Harris, charlatans like Anchor, or spiritual mysticism like the Dalai Lama (someone I do greatly admire), you have to go all the way to the seventh page of search results on Amazon before you come across a book titled, coincidentally enough, Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert. This book has a little over 500 reviews on Amazon as of this writing and so would not necessarily show up as the first search result. However, it is written by a social psychologist who received his PhD from Princeton University and now works at Harvard where he does in fact research human happiness and has done so for the length of his career. Peer-reviewed Expertise While popular psychology books like Gilbert’s are great, they are still written with sales in mind and try to package material in ways that are palatable to their general public audiences. This can be fine, but it can also put focus on topics that might not be as important as the field of research in general suppose them to be. An even stronger start would be to find a textbook on the subject, even if it is an undergraduate introductory text. This will contain the broadest survey of agreed upon facts, important researchers, and controversies within the research community of the given field and not be filtered through just one researcher’s and his or her publicist’s and publisher’s demands. These types of books usually won’t even show up in the search results because they have such few reviews on platforms like Amazon. An example textbook, A Primer in Positive Psychology, which is very readable, has only 43 reviews - a far cry from the 2,200 for Harris. In fact, you wouldn’t find it just by searching through the most reviewed books on happiness because it isn’t even labeled under that category. It is labeled in the categories of “social psychology”, “reference”, and “education”. This is where understanding how key word searches can fail you is important. Sometimes it is worth figuring out the field of research that studies the topic you’re interested in - in this case positive psychology is the field of research that studies the topic of happiness. Searching for just they key word of happiness may not get you to the best source of information as described immediately above. So generally speaking, people interested in a field of technical knowledge should begin with either a popular book like Gilbert’s or an introductory textbook. Both of these have information that have been evaluated against the entire field of research by professionals who spend their entire careers immersed in the subject. This is a much stronger base than beginning with a book written by someone like Harris, who simply did some investigative journalism and regurgitated it into a book without having a background in the topic himself. It’s his media platform and minor celebrity that earned his reviews, not his credentials to talk about the subject. Of course, no one is saying that you only have to read one book on a subject and it is always good practice to read multiple sources. However, if you were to read just one book, the textbook is recommended over the journalist every single time. Procedural Knowledge Another large area of knowledge is that of procedural knowledge. This is knowledge that requires practice and skill development. Things like learning to play a sport or instrument are good examples. This is the type of knowledge typically studied by the field of expertise under the topic of deliberate practice. Here the advice is much simpler and straightforward. Find someone with the hat trick. What’s the hat trick? The hat trick is when a person has three different and specific types of credentials: technical knowledge, personal experience, and coaching experience.

Conclusion If one is going to spend the time to learn something, it is worth getting the best information possible. This often takes very little extra effort on one’s part. The above rules for doing so can help enormously. For technical knowledge, find technical experts. Read their books. Watch their YouTube lectures. Take their classes. Enroll in their programs. For procedural knowledge, find somebody with the hat trick. That is, find someone who has a degree of technical knowledge in the procedural knowledge you wish to attain, has personal experience with the procedural knowledge themselves, and has already gained success for others by applying their technical knowledge and personal experience. The most important aspect in acquiring either of the two types of knowledge outlined in this article is knowing what you are after. Always take the time necessary to focus your goal(s) so that you know what you are really aiming for. If you don’t have a clear target, you’ll never be successful, regardless of the qualifications attached to the knowledge you gain. Democracy is a difficult form of government to get right. It requires a delicate balancing act of education, non-discrimination, and non-repression. These components make it possible that representatives, policies, and legislation are selected that benefit as many people as possible without tyrannizing over minority groups and individual rights. This requires a nation’s education system to be robust so that individuals learn how to think critically about issues and for the media to provide adequate information on facts for the public to deliberate on.

This deliberation can become very messy, complex, and nuanced. It’s hard not to in any society that has cultural diversity and pluralistic values. Beliefs will often conflict and create situations in which at least one party will potentially lose. Even when that is true, the public should hope to elect representatives that understand this messiness and make decisions with the greatest benefit in mind. Democratic Deliberation The main issue seems to be that democracy requires deliberation among the electorate on how best to organize society. Societal organization can’t hope to land on the best system on the first try. It requires constant change and experimentation. Even if democracy did select the best possible organization for society on the first try, it would need constant updating and change due to fact that new people and needs will enter the system over time and change the balance of what is best. In order to choose the best organization for this moment in time, the voting public needs to have access to information. If the public doesn’t have access to valid, nuanced information, they can’t deliberate from facts. Deliberation in a democracy ought to be based on reason, argument, and evidence. If the public is voting on a candidate that is addressing a complex issue like immigration, they ought to be aware of exactly how immigration affects the country in both the short and long term. This requires understanding complex ideas in economics and politics and cannot be boiled down to a simple headline such as, “Immigrants Steal Jobs” or “Everyone Wins with Free Trade”. The Media News outlets are our primary source for the information we need in making choices. These news outlets can be either publicly or privately owned and both have negatives. Public ownership of news outlets has the potential to be abused by currently sitting politicians who can manipulate information to their advantage. Private ownership, as the majority of the media system is structured now, obligates companies to maximize profit if they have shareholders and generally compete with firms to remain open and be able to cover their costs. This latter point often requires getting as many eyeballs on the news outlet’s channel or paper as possible. In order to do this, media sources act much like other companies in that they turn to catchy headlines and soundbites that drive ratings, in essence giving their customers what they want. Many people have written about the “banality of good”, but I like Matthieu Ricard’s short summary from Altruism best when he writes, “everyday good does not make much commotion and people rarely pay attention to it; it doesn’t make the headlines in the media like an arson, a horrible crime, or the sexual habits of a politician” (p. 94). Complexity versus Simplicity One way of interpreting the media’s insistent negative press is to view it as a product of “cause and effect” thinking. Most of modern society has been built on the scientific method in some capacity. We use it everyday, even if we aren’t always aware of it, to make our lives better. The roads we drive on, the buildings we inhabit, the food we eat, and just about everything else we can point to is a product of scientists’ and engineers’ thinking very hard about how to improve our lives by searching for cause and effect relationships and isolating variables. However, this reliance on cause and effect thinking that arises from our societal love of the scientific method creates a problem when situations are complex. We intuitively look for a single cause and try to point to it as the solution of whatever problem we might be facing. This has the typical result of destroying nuance and multidimensionality in problem solving. This destruction of nuance and complexity when it is needed, such as in the political and economic arena of democracy, makes differentiation among candidates difficult without resorting to moving away from the center to more extreme positions. Partisan Extremism Now we come to the real problem. Democracy requires information. That information is distributed by news outlets that must maintain ratings to make a profit. This forces the media to focus on simple and direct cause and effect thinking that is easily captured in soundbites and short phrases, or even single words. This simplification of what is needed for positive change by eliminating nuance and complexity promotes extreme positions taken by candidates for a very simple reason - the need to differentiate to win votes. Think about it this way. If you know that whatever you say will be captured in a headline and that many people will not read the entire story or place it within a larger context, you cannot argue over details and minutia that separate you from another “center” candidate. You have to aim at a headline that will grab attention while avoiding complexity. This necessitates a move outward to further positions on the left or right or you will sound just like every other candidate when broken into center-positioned soundbites by the news. We see this today on both sides of the political spectrum in America. A good example from the Democratic platform was Obama’s entire 2008 message of “Hope” and “Change”. You literally can’t get anymore simple than single word platforms, but in reality these two words are meaningless outside of complex contexts and it would be genuinely idiotic to endorse him and his party on the basis of these two words. We ought to immediately ask ourselves, “What kind of change? What specific things do you plan to change, and how?” This obviously involves much more digging into details and specifics with possibly conflicting solutions for multiple problems. But until we know these things, we can’t assume any change is good change. Plenty of change can be bad. Which takes us to his second message of “Hope”, which is essentially the opposite of what we should be looking for in a candidate. The electorate should not be closing their eyes, crossing their fingers, and hoping for a better tomorrow. They should be digging into the messiness that is political economy with eyes wide open and experimenting with solutions continuously to see what does and does not work. This requires no hope at all. Just a willingness to do the work. And a willingness to suffer through some failures of experimentation to arrive at a better future. Getting to the Point The point is positive improvement for the greatest number. Democracy generally accomplishes this better than other systems we have experimented with as humans trying to organize society, but that doesn’t mean it is perfect. The system itself pushes potential representatives to extreme positions in their attempt to differentiate and win elections. Occasionally, an extreme position may be just what is called for, especially on issues that entail more socially inclusive policies around human and civil rights for disenfranchised, discriminated against, or oppressed members of a society. But more often than not, the changes necessary to make daily life better for all require a holistic image of the entire system and how it will be impacted by shifts of its different components. This type of “routine” change doesn’t require flashy language and partisan extremism. It only requires engaged, caring, and knowledgeable representatives who have everyone’s best interests at heart. In cases like these, sometimes (most often) the best candidate will be the boring one who has done the work, not the exciting one who yells the loudest. I’ve always exercised for only a couple of reasons: to feel able enough to experience more of life and to avoid preventable diseases and injuries as I age. The latter reason is the primary impetus for me even when I feel unmotivated, but the former is a nice perk, almost a bonus as it were, and what has given me some of my best memories and feelings of accomplishments. Examples of the experiences I’ve had because of physical health include climbing Mount Whitney and Mount Baldy in California with some of my closest friends, squatting 402 pounds, deadlifting 500 pounds, running two half marathons, completing a triathlon, doing 20 pull ups at one time, spearfishing in Malibu, and otherwise enjoying outdoor leisure activities such as camping, hiking, bodysurfing, and various board sports. These memories and accomplishments due to physical health rival every other good memory I have outside this realm of physicality, including earning a Master’s degree, self-publishing Kindle and Audible books on Amazon, getting married, and helping students learn about and fundraise for valuable organizations. However, as I said above, it is really the prevention of diseases and injury that motivates me to maintain a minimum of physical health. Anyone who doesn’t know me that well won’t know this, but I’ve grown up with a father that has a genetic variation of emphysema. It is a disease that, as he has described it, “takes one new thing away from you each day, week, or year”. It’s progressive and miserable. He used to be able to lift heavy weights, run trails through the California hills and mountains, and play tennis vigorously as a serious hobby. Now, he is lucky to finish 18 holes of golf while using a cart and oxygen the entire time. Bending over to remove weeds in the garden can make him lightheaded and dizzy. Even showering, dressing, and putting on shoes and socks (bending over again) can be exhausting. With his ever looming physical presence in my house, I’ve been interested in warding off major surgeries and illnesses via prevention since I was a teenager. The 10 Leading Causes of Death Worldwide According to the World Health Organization approximately 56 million people die each year and the leading causes are as follows: Ischaemic heart disease, stroke, lower respiratory infections and chronic obstructive lung disease have remained the top major killers during the past decade. Leading Causes of Death in the USA According to the Center for Disease Control, the leading causes of death of the approximately 2.5 million annual deaths in America are:

To be even more specific, according to Harvard’s School of Public Health, approximately 2 million (of the 2.5 million total) deaths are preventable each year and are due to “dietary, lifestyle and metabolic risk factors”. The number of deaths annually due to these specifically preventable risk factors are:

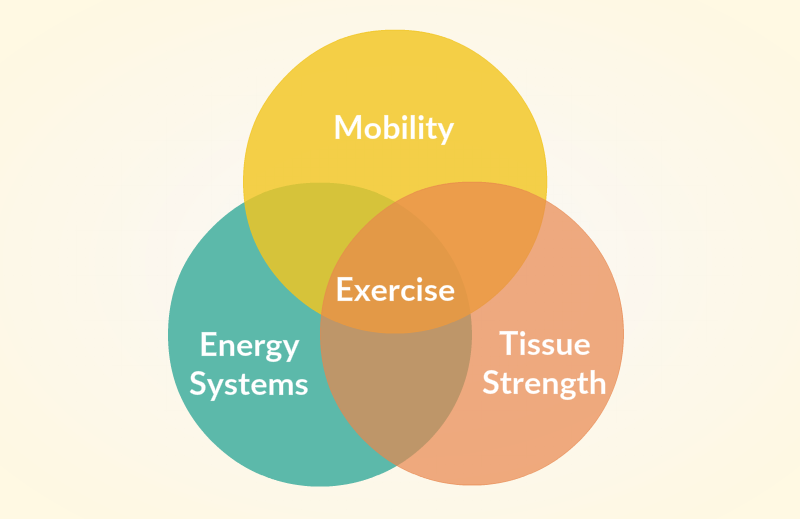

And to be even more specific still, according to the CDC again: Falls are the leading cause of injury-related morbidity and mortality among older adults, with more than one in three older adults falling each year, resulting in direct medical costs of nearly $30 billion. Some of the major consequences of falls among older adults are hip fractures, brain injuries, decline in functional abilities, and reductions in social and physical activities. Although the burden of falls among older adults is well-documented, research suggests that falls and fall injuries are also common among middle-aged adults. One risk factor for falling is poor neuromuscular function (i.e., gait speed and balance), which is common among persons with arthritis. In the United States, the prevalence of arthritis is highest among middle-aged adults (aged 45–64 years) (30.2%) and older adults (aged ≥65 years) (49.7%), and these populations account for 52% of U.S. adults. Moreover, arthritis is the most common cause of disability. (p. 379) What this all points to, if you live in the United States in particular, is a need to address long-run physical issues through prevention. Avoiding smoking, drinking, trans fatty acids, and high dietary salt and sugar aren’t that difficult. Neither are including poly-unsaturated fats, fruits, vegetables, omega-3 fatty acids, and exercise. Even though diet is clearly very important from reading the above, I find most people understand and know this. Rather, like flossing and other simple things involving willpower, they simply choose not to eat and drink well because of a host of reasons, sometimes individually based, but often social as well. What I find most people don’t do is make clearer connections to their exercise choices and the long-run prevention strategies that should become obvious as one looks over the data above. Exercise has a clear and robustly supported impact on some of the largest causes of death in the United States. Causes of death such as heart disease, respiratory disease, Alzheimer’s disease, intentional self-harm, high blood pressure, overweight-obesity, and the number one cause of death in old age, “falls”, are all directly connected to and can be decreased by our choices of exercise. So let’s examine what I believe to be the best overall approach to longevity given what the data above tell us. The Algorithm EfL = f(M, TS, ES) Exercise for longevity is a function of our mobility, tissue strength, and energy systems. Of course, overall health and well-being will include more than exercise. As mentioned above, diet will be one large aspect. Sleep would be another. Stress yet a fourth. And take a look at my algorithm for subjective well-being for variables regarding your mind, which also have a strong impact on your physical health. PH = f(D, S, E, St) Physical health is a function of diet, sleep, exercise, and overall stress levels. I won’t go into all the variables in the PH equation directly above, but will spend some time fleshing out the first equation on exercise for longevity. Mobility This dimension seems to be the most confusing to people. As physical therapist Charlie Weingroff puts it: Being fully mobile simply means the ability of a joint system to move through a definable range. This definition is great because it puts mobility into perspective. Mobility’s job is to let you do the tasks you wish to do. Nothing more. Being able to do a full splits may demonstrate extreme mobility of your hips, but if it doesn’t let you perform any other tasks that you deem important, then it is probably a bit silly to spend an inordinate amount of time gaining that ability. Gray Cook, another physical therapist, states it nicely when he urges us to “manage our minimums”. Our lack of mobility often gets us in trouble when it is asymmetric more so than when it is somewhat limited. What all this means is that you don’t have to take up yoga to become more “flexible”, i.e. mobile. You don’t win points for being more mobile than someone else unless that person can’t live a normal, independent life because of their poor ranges of movement. In general, once you decide that you do need to improve your mobility, physical therapy work will be the most effective practice, much more so than simply stretching. “You need a trigger point technique, a soft tissue technique, and a joint technique.” A good place to start for self maintenance is on physical therapist Kelly Starrett’s Mobility WOD. If you really do have mobility issues, this will get you much further than yoga or static stretching in much less time and energy. But again, mobility is relative to what you want to do with yourself. With longevity in mind, you are mostly worried about being able to get up and down off the floor and up and down off the toilet, along with reaching upward or downward to grab or pick up things. Those are really the biggest demands on most people’s mobility as they age. Anything past that will be mostly individual wants and needs. What improved mobility won’t do is prevent any of the major causes of death described above except perhaps “falls”, but this is more often related to muscle weakness and atrophy and is better addressed in the next dimension of exercise - tissue strength. Tissue Strength Human tissues come in two forms: soft and hard. Soft is easier to describe as saying it is everything that isn’t hard tissue, i.e. bone and tooth. That means that soft tissue comprises tendons, ligaments, muscles, fascia, nerves, blood vessels, skin, and a few others. In strengthening both hard and soft tissue, one can alleviate the chances of several of the risks above, including accidents, diabetes, high blood pressure, overweight-obesity, and inadequate physical activity. The best way to strengthen your bodily tissues is to exert stress on them through external weight. This means weight training, strength training, bodybuilding, Crossfit, or whatever other form of training you wish that involves weights of moderate load (60-85% of maximum), for moderate repetitions (5-20), and moderate sets (3-10). This is because weight training is the most effective way to increase bone density, tendon/ligament strength, muscle size, and regulate blood pressure, hormones, and hypertension. Basically, “Barbell training is big medicine.” The three best understood methods for maintaining muscle size and strength according to Brad Schoenfeld, PhD in exercise science, are through mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress. Mechanical tension is created on a muscle, bone, tendon, or ligament any time we use a relatively heavy load. This is generally understood to be 60-100% of our maximal effort. Muscle damage is best elicited through exercises that have not been done recently, by providing a greater than normal stretch or lengthening of a muscle, and the use of heavy or slow eccentrics (lowering of a weight). Lastly, metabolic stress is the buildup of metabolites in a muscle and is best described as the “burn” we feel in our muscles from repeated contractions with little rest. Basically anything that Arnold Schwarzenegger would have described as a “pump” back in the 70’s is likely to induce metabolic stress in a muscle. A host of interrelated reasons explain why increased tissue strength and size are so effective at combating the above risk factors. Accidents are far less likely when we have strong bones and muscles that we have learned to coordinate through the coordination of our own bodies and external weights. Diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity have nearly zero chance of occurring with frequent weight training because more muscle means a higher rate of metabolism, as our tissues are where metabolism occurs. The repeated spiking of blood pressure during weight training actually works as a stressor that keeps our blood pressure lower when not exercising, just like raising our heart rate during running keeps our heart rate lower when not running. This type of exercise also has a large and positive impact on our hormones, causing several to be released and regulated in a healthy manner. Jonathon Sullivan, MD and PhD in physiology, summarizes all of these effects from strength training on longevity perfectly: And before you ask: at present there is absolutely no solid evidence that strength training—or any other exercise or dietary program—will substantially prolong our life spans. But the preponderance of the scientific evidence, flawed as it is, strongly indicates that we can change the trajectory of decline. We can recover functional years that would otherwise have been lost. There is much talk in the aging studies community about “compression of morbidity,” a shortening of the dysfunctional phase of the death process. Instead of slowly getting weaker and sicker and circling the drain in a protracted, painful descent that can take hellish years or even decades, we can squeeze our dying into a tiny sliver of our life cycle. Instead of slowly dwindling into an atrophic puddle of sick fat, our death can be like a failed last rep at the end of a final set of heavy squats. We can remain strong and vital well into our last years, before succumbing rapidly to whatever kills us. Strong to the end. Energy Systems Finally we come to energy systems training, which can help prevent the major causes of death, including heart disease, respiratory disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and suicide due to depression. We actually have three overlapping energy systems. These include the phosphagen system, anaerobic system, and aerobic system. The first two are used for short-term, high-intensity outputs like jumping, sprinting, weight lifting, etc. You can typically sustain the phosphagen system for up to 10 seconds and the anaerobic system for a couple of minutes (think 800 meter run) before you start to feel your lungs and muscles scream and burn. Both of these are easily addressed with whatever weight lifting you do for strengthening your tissues, but interval training can also do the trick. The third system, aerobic energy, uses oxygen and is what most people think of when they think of “cardio”. Anyone swimming, biking, jogging, or otherwise covering a lot of ground over a long time will be using this energy system. However, people today seem to have gone to extremes with ultramarathons, Ironman triathlons, and century bike rides. Andrew Hallam, summarizes the research well when it comes to cardio: Earlier this year, five researchers published a study in the Journal Of The American College of Cardiology. They found that, on average, joggers live about 6 years longer than couch potatoes. But those who run too far, too fast, or too frequently die earlier. They live about as long as a typical T.V. loafer. Putting It All Together

While all of this seems rather complicated, it’s actually quite simple. To do our most to prevent long-term health problems due to illness, injury, and death when it comes to exercise, we essentially want to physically train much like a bodybuilder. This means:

This will keep our tissues strong and healthy, our cardiovascular system in optimal condition, and our joints and movement patterns capable of the ranges of movement we need so we don’t succumb to dying by “fall” once we get over the age of 65. If we are living up to and beyond our 70’s and 80’s, we must plan accordingly. I’ve seen my dad suffer from pretty much all of the major risks above, including heart disease, lung disease, overweight-obesity, accidents, depression, and those are just the ones I know about. I do not wish to suffer the same as I age, especially as I don’t have any genetic reason why I would. None of this needs take any longer than traditional hour long classes at a local gym or the 10K you run 4 times a week either. Thirty minutes of weights, followed by 20-30 minutes of cardio, and zero to 10 minutes of mobility work will still only take an hour out of your day and can be done just two to four times a week like most recreational exercisers do anyway. Conclusion While the algorithm best suited for ensuring longevity from exercise is rather short and straight forward, it doesn’t take into account a host of other factors, some of which were touched upon earlier regarding diet, sleep, stress, smoking, drinking, and risky sex practices. In addition, it’s equally important to point out that on a day to day basis, driving is one of the most dangerous activities that we participate in and anything that you can do to reduce the miles driven on roads, the better. It’s also worth noting that accidents are the number one cause of death in the 25-44 age group and that suicide, homicide, and liver disease are numbers four, five and six. This implies that living in a country or city like Singapore, where a person typically drives less because of efficient public transport, has access to good psychological health services, is very unlikely to be a victim of homicide, and is forced to pay expensive cigarette and alcohol taxes, can actually be of great service in making it through a person’s midlife and into their later years unscathed by youth. I also realize that the most popular forms of exercise are not actually included in this algorithm. Yoga, running, biking, and swimming (ultra) long distances, Zumba, Pilates and the like really have almost no use outside of the psychological and social benefits they might provide you, which I think is what most people are actually searching for when they undertake these activities. They are similar in nature to the glass of wine people drink after work “for the health benefits”. The truth is they just make you feel better. The goal of this algorithm regarding exercise for longevity is ultimately to fill gaps in thinking for people. Many view running as a complete exercise program or something like yoga and Pilates as “all you need” for complete physical health. This is objectively not true. While both of these types of exercise give some narrowly received benefits, they completely miss the tissue strength enhancements that will be your biggest ally in in keeping independence and functioning in old age and do little to ward of the metabolic diseases of modernity. It isn’t that you can’t do the things you love and enjoy. It’s that by going about designing and thinking about exercise on the basis of what is objectively needed to prevent our leading causes of death and injury, we can also feel subjectively better. There are very few things as subjectively rewarding as being physically fit in all three of the dimensions described above: mobility, tissue strength, and energy systems. At the end of the day, there is no problem with doing things because they make you feel better psychologically, but it is important to separate facts from the delusions we often tell ourselves and realize that empirically and objectively arrived at choices for exercise can also be enjoyed subjectively while keeping you healthier in the long run. Even if it means learning and doing new things you initially find uncomfortable or possibly even painful, the payoff for both you and society is more than worth it. If we accept that most of life is suffering and we are goal seeking entities, then inquiries naturally follow about what sorts of goals and activities let us avoid boredom and suffering while experiencing joy. A recent conversation and extensive bout of reading has driven me to explore these questions in more deeply than I have previously. Below is my attempt to develop answers in which I will find recourse to extensive quotes from my most recent reading. Boredom In The Reasons of Love, Harry G. Frankfurt describes boredom and its connection to goals and joy in the most beautiful manner I’ve seen to date. He paints boredom as not just an uncomfortable state of being, but as essentially an attack on our vitality and the death of our self: It is an interesting question why a life in which activity is locally purposeful but nonetheless fundamentally aimless— having an immediate goal but no final end— should be considered undesirable. What would necessarily be so terrible about a life that is empty of meaning in this sense? The answer is, I think, that without final ends we would find nothing truly important either as an end or as a means. The importance to us of everything would depend upon the importance to us of something else. We would not really care about anything unequivocally and without conditions. Naturally, if we understand accept Frankfurt’s description of boredom, we would want to figure out a way to prevent it and at the same time find a method for selecting a non-local goal (i.e. a final end). Thankfully, he doesn’t make us wait long, as he immediately turns to answering this question: There must be certain things that we value and that we pursue for their own sakes. Now it is easy enough to understand how something comes to possess instrumental value. That is just a matter of its being causally efficacious in contributing to the fulfillment of a certain goal. But how is it that things may come to have for us a terminal value that is independent of their usefulness for pursuing further goals? In what acceptable way can our need for final ends be met? This too makes a lot of sense, but we should investigate what Frankfurt means by love and the use he applies to it here. He does this most brilliantly in a separate work discussing the value of truth. Love and Joy In On Truth, which looks at the nature of truth and why we as humans should value it, Frankfurt finds it useful to build on the work of Spinoza, one of the first humanist philosophers in spirit: Spinoza explained the nature of love as follows: “Love is nothing but Joy with the accompanying idea of an external cause” (Ethics, part III, proposition 13, scholium). As for the meaning of “joy,” he stipulated that it is “what follows that passion by which the…[individual] passes to a greater perfection” (Ethics, part III, proposition 11, scholium). The above account is perhaps the single best explanation of joy and love that I have come across. I have added emphasis to three points above because the first two resonate deeply with me, but the third point on “necessarily striving to have present and preserve” does not. In fact, this having orientation to life in which we feel possessive towards the things that bring us joy is described in great depth by Erich Fromm in his landmark work, To Have or To Be, as one of the prominent causes of suffering in our world due to the fear and insecurity that it engenders. Insecurity By attaching our self to the things we have or can possess, such as Spinoza (Frankfurt) describes above, we live with the fear of losing those possessions and with them our identity and sense of self. Fromm describes this magnificently below where he contrasts the having mode of existence with the being mode: If I am what I have and if what I have is lost, who then am I? Nobody but a defeated, deflated, pathetic testimony to a wrong way of living. Because I can lose what I have, I am necessarily constantly worried that I shall lose what I have. I am afraid of thieves, of economic changes, of revolutions, of sickness, of death, and I am afraid of love, of freedom, of growth, of change, of the unknown. Thus I am continuously worried, suffering from a chronic hypochondriasis, with regard not only to loss of health but to any other loss of what I have; I become defensive, hard, suspicious, lonely, driven by the need to have more in order to be better protected. Ibsen has given a beautiful description of this self-centered person in his Peer Gynt. The hero is filled only with himself; in his extreme egoism he believes that he is himself, because he is a “bundle of desires.” At the end of his life he recognizes that because of his property-structured existence, he has failed to be himself, that he is like an onion without a kernel, an unfinished man, who never was himself. Earlier in To Have or To Be, Fromm does take the time to explain with a few examples just what types of activity might be included in “expressing our essential powers”. Essential Powers It is easy to notice that all of the powers below “grow by practice” as Fromm describes above and so it is not difficult to use them as guideposts for other activities that are not included. The critical difference between activities that are classified as having or being modes of existence is the resultant “awareness of a more vigorously expansive ability to become and to continue as what we most truly are. Thus, feeling more fully ourselves. We feel more fully alive,” as Frankfurt described with reference to Spinoza above. Fromm uses the Shabbat and Hebrew prophets as examples: On the Shabbat one lives as if one has nothing, pursuing no aim except being, that is, expressing one’s essential powers: praying, studying, eating, drinking, singing, making love (emphasis added). The Shabbat is a day of joy because on that day one is fully oneself. (p. 51) The point with the Shabbat as described here is not that people have nothing, but that “one lives as if one has nothing”. These experiences cannot be taken from us because they are not “possessions” which we can be deprived of. Fromm continues on to describe the manner in which “being” was taken up after the loss of “everything the Jews had”: The real successors to the Hebrew prophets were the great scholars, the rabbis, and none more clearly so than the founder of the Diaspora: Rabbi Jochanan ben Sakai. When the leaders of the war against the Romans (A.D. 70) had decided that it was better for all to die than to be defeated and lose their state, Rabbi Sakai committed “treason.” He secretly left Jerusalem, surrendered to the Roman general, and asked permission to found a Jewish university. This was the beginning of a rich Jewish tradition and, at the same time, of the loss of everything the Jews had had: their state, their temple, their priestly and military bureaucracy, their sacrificial animals, and their rituals. All were lost and they were left (as a group) with nothing except the ideal of being: knowing, learning, thinking, and hoping for the Messiah (emphasis added). (p. 53) Moreover, Fromm later describes exactly what does differentiate pleasure from joy as he understands it, relying on none other than the same person Frankfurt did earlier - Spinoza: Yet the distinction between joy and pleasure is crucial, particularly so in reference to the distinction between the being and the having modes. It is not easy to appreciate the difference, since we live in a world of “joyless pleasures.” The only thing then left to consider is the “goal of becoming ourselves” and the “model of human nature we have set before us”. I believe this is best taken up by Nel Noddings’ in her work Caring, which lays out an ethical ideal predicated on just the type of loved described above by Frankfurt from which interest, joy, and our truest selves can spring forth. The Ethical Ideal and Self What is this “ethical ideal” I have referred to? When I reflect on the way I am in genuine caring relationships and caring situations— the natural quality of my engrossment, the shift of my energies toward the other and his projects— I form a picture of myself. This picture is incomplete so long as I see myself only as the one-caring. But as I reflect also on the way I am as cared-for, I see clearly my own longing to be received, understood, and accepted. There are cases in which I am not received, and many in which I fail to receive the other, but a picture of goodness begins to form. I see that when I am as I need the other to be toward me, I am the way I want to be— that is, I am closest to goodness when I accept and affirm the internal “I must.” Now it is certainly true that the “I must” can be rejected and, of course, it can grow quieter under the stress of living. I can talk myself out of the “I must,” detach myself from feeling and try to think my way to an ethical life. But this is just what I must not do if I value my ethical self. By now we can see a somewhat hazy picture breaking through. In order to preserve the self and not allow boredom to destroy us, we must cultivate final ends. These final ends are found in love resulting from joy, which is “what we experience in the process of growing nearer to the goal of becoming ourselves”. This calls for us not to pursue pleasure and possession, but to make choices that favor relations of caring, our “basic reality”. Obligation In the pursuit of caring relations, we necessarily develop obligations to those we care for. Noddings does an equally marvelous job of elucidating how these obligations arise and where the boundaries ought to be formed: Now, this is very important, and we should try to say clearly what governs our obligation. On the basis of what has been developed so far, there seem to be two criteria: the existence of or potential for present relation, and the dynamic potential for growth in relation, including the potential for increased reciprocity and, perhaps, mutuality. The first criterion establishes an absolute obligation and the second serves to put our obligations into an order of priority. What these two criteria clearly outline is a method for how and when to enter more deeply into caring relations - the ultimate source of joy, love, and growth of our truest selves. This is important because we are otherwise left to the tragic logic of utilitarianism with its impartiality and concern for all. That path quickly and dangerously leads us to become “happiness pumps” for all other sentient creatures in which we can quickly become depressed due to our helplessness: the belief that suffering personal, permanent, and pervasive. Instead, we can engage actively with others on the basis of their presence in our lives in the here and now and the “dynamic potential for growth in relation, including the potential for increased reciprocity and, perhaps, mutuality”. Self-actualization This valuing of caring as the preeminent method to achieving “self-actualization”, the highest form of “being” as Maslow put it, must always be done by keeping in “in mind, however, that the second criterion [of caring] binds us in proportion to the probability of increased response and to the imminence of that response,” as Noddings writes above. This is seconded quite clearly in another of Fromm’s passages from To Have or To Be: The most relevant example for enjoyment without the craving to have what one enjoys may be found in interpersonal relations. A man and a woman may enjoy each other on many grounds; each may like the other’s attitudes, tastes, ideas, temperament, or whole personality. Yet only in those who must have what they like will this mutual enjoyment habitually result in the desire for sexual possession. For those in a dominant mode of being, the other person is enjoyable, and even erotically attractive, but she or he does not have to be “plucked,” to speak in terms of Tennyson’s poem [about a beautiful flower], in order to be enjoyed. So while interpersonal relations are the source of our love, interest, joy, caring, and ultimately our final ends, we must be constantly vigilant as to not turn them into our greatest sources of misery as well. Striving to have others and possess those we love is not love at all, merely an appearance of it. The above passage does give a quiet hint as to why people might pursue possessive having love over true, meaningful, being love. That is fear. However, whereas Fromm posits that fear of losing our “possessions” drives us to fortify our positions by gaining ever more and thereby driving competition and antagonism, fear also drives us to avoid being. In order to be, we must “unmask” ourselves in front of others and allow them to see us as we really are. “This concept of being as ‘unmasking,’ as is expressed by Eckhart, is central in Spinoza’s and Marx’s thought and is the fundamental discovery of Freud” (p. 97). This unmasking requires “daring greatly” as Brene Brown has written about extensively. Daring greatly can be threatening because we expose ourselves and open our inner worlds to others who are able to judge us, accept us, or reject us and possibly trample on our vulnerability. In seizing this mode of being, Noddings explains: One under the guidance of an ethic of caring is tempted to retreat to a manageable world. Her public life is limited by her insistence upon meeting the other as one-caring. So long as this is possible, she may reach outward and enlarge her circles of caring. When this reaching out destroys or drastically reduces her actual caring, she retreats and renews her contact with those who address her. If the retreat becomes a flight, an avoidance of the call to care, her ethical ideal is diminished. Similarly, if the retreat is away from human beings and toward other objects of caring— ideas, animals, humanity-at-large, God— her ethical ideal is virtually shattered. This is not a judgment, for we can understand and sympathize with one who makes such a choice. It is more in the nature of a perception: we see clearly what has been lost in the choice. (p. 89-90) And while the ethical ideal may be “shattered” and we may “see clearly what is lost”, Fromm assures us that: The only threat to our security in being lies in ourselves: in lack of faith in life and in my productive powers; in regressive tendencies; in inner laziness and in the willingness to have others take over my life. But these dangers are not inherent in being, as the danger of losing is inherent in having. (p. 109-110) Conclusion: Making the Change Much of modern society is a never ending roller coaster of boredom, excitement, pleasure, and fear as discussed in depth above. None of these states and experiences need be innate to our existence. We can choose a radically different mode of living and being. We can choose to pursue activities that enlarge our capacities and inner powers towards “a greater perfection”, that form deeper, caring connections to others, that result in joy and love and ultimately a sense of vitality and exhilaration. Ultimately, everything above requires a change of character. This change in character is possible. Not only is it the premise of the entire modern day field of positive psychology that character change is possible, but Fromm outlined the path to personal change quite perfectly over 40 years ago in 1976, when he drew on the Four Noble Truths from Buddhism, Marx, and Freud to write the following in To Have or To Be: I suggest that human character can change if these conditions exist: In following the above four step process of becoming a new person, Fromm held that the following qualities would be exhibited:

Any world in which the above qualities make up the majority of individuals’ beliefs and values is a world that would be radically different than our current reality. We desperately need this positive change. The above has been an outline focused on providing direction for change based on some of the brightest minds and their findings over the past century. So stop chasing the excitement and pleasure that ultimately leads to boredom and contraction of the self and instead choose to pursue joy and the ever enlargement of your capacity to be more fully human.

|

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed