|

Below is about 4,700 words on deciding whether or not having children is a good idea. Because this started as a blog post, but took so long to write and became so long, Rebecca and I have both decided to publish it in its entirety as a blog post while also publishing it as a very short Kindle eBook for $2.99. Whether you read it for free here or decide to purchase it is entirely up to you, but we would obviously appreciate your support if you found anything helpful, useful, or enlightening from this dialogue. Click here to visit the Amazon Kindle page or click the image below.  Preface Kyle: I have personally wanted to be married and have kids since I can remember. For most of my life it was simply a want, a desire, not reflected on or thought about in any capacity. It was and still is mostly supported by my family, friends, acquaintances, and society as an expected pursuit and worthwhile desire. I was raised by parents that did not try to influence me too much in anything related to politics, religion, or family life. As a result, I just went to school, learned those lessons (mostly liberal), and began reading about topics I was uncertain of and wanted to know more about. It was only reasonable to me to ask questions about the large issues in life, with children being one of the largest decisions any of us make. As I read more about bringing a life into existence and the ethical implications of that choice, I became more and more convinced it could not reasonably be viewed as ethical or the moral thing to do. This belief crystallized more and more over the last couple of years and I suddenly found myself in a position of having to throw off a two-decade-old wish. It was at this point that I met Rebecca and began to discuss these ideas with her. She was able to listen to and hear all of my reasons and arguments for no longer wanting children and rationally come to a different conclusion on the ethicality of the decision. It was because of this openness to conversation and her obvious use of all aspects in decision making - emotion, empathy, reason, evidence, logic, optimism, expectation - that I decided to explore this particular decision in written form with her. We have attempted to figure out exactly how the decision to have a child benefits the child itself, the parents, the community and greater world beyond ourselves. In doing so, we primarily rely on a moral system based on the ethics of care and well-being, both of which can be argued against as the most rational basis of morality, but which science, psychology, and philosophy are all mounting more and more evidence in favor of and select as the proper norm. Rebecca: For me, wanting to be married and have children has never been a question, thought, or consideration. It has been a drive and a focus for as long as I can remember. It is also the only area of my life that had originated and existed largely without question or self-exploration. In that sense, the intention to raise a family with a partner without asking myself why is largely inconsistent with the rest of my character. I’d grown up in a household where I was always encouraged to read, ask, and seek out answers to my questions. It ultimately struck me as odd that I had no questions about what I had always seen as the pathway to adulthood and happiness. As an educator, I have always emphasized that my students need to have reasons, explanations, and evidence to support their claims and decisions. I realized that I had not done the same with my own hopes for marriage and children, that I had committed the error of “do as I say, not as I do”. When Kyle and I started discussing education, improving the world, and our personal rationalizations and goals, I started to ask the questions that I had never quite verbalized previously. This has led me to explore the ideas presented below in written dialogue with him. We both hope that others find this conversation, in terms of content as well as construction through honest reflection, openness, and communication, helpful and encouraging as a way of engaging in their own dialogues and explorations about other areas of life. Having Children: A Dialogue Kyle: Let’s start with the question of the benefit to the actual future child a parent brings into the world. Do you see coming into existence as ever being of benefit to the child itself? Rebecca: I have to operate on assumptions to answer this question. If we’re assuming that living is better than not living, then yes. If it is better to exist than not exist, coming into existence is better for the life of the child because of the experiences and opportunities that life has to offer. This child can learn and grow and travel and have a positive impact, all of which will benefit the child itself. Kyle: So many questions. First, why are you starting from the assumption that living is better than not living? Second, if coming into existence is good for the child itself, many people have considered the idea that we have an obligation to create life. Should we not simply create as many children as possible? If it is a good in itself, we might consider that an obligation exists to simply propagate as many children as we can. Last, having a positive impact does not necessarily benefit the child. I need more explanation on how that is good for the child itself. Obviously, a “positive” impact by definition would be good for someone or something else, but I don’t see the connection to that being good for the child or a reason to bring it into existence in the first place. Rebecca: Good questions. From a species perspective, living is better than not living. Obviously humans need to reproduce if the human species is going to survive, so this means that the child’s existence doesn’t inherently benefit the child, but humanity. However, I wouldn’t say we have an obligation to create life because the benefit to humanity with this child only exists if the parents are making a deliberate choice to raise and rear the child with clear aims of making the world a better place. This would impact parenting and educational decisions about the child. Having children for the sake of having children just increases the world’s population, which is already increasing more quickly than is currently sustainable. If parents decide to have a child and are raising the child to have a positive impact on the planet and on humanity, that is a good reason to bring a child into existence. The child’s participation in making the world better and then inhabiting a better world is ultimately good for the child. Kyle: So you mention the benefit to the species, which would be a slightly different discussion altogether relative to the current one on whether bringing the child into existence benefits it at all. You also mention population sustainability, which has the same issue. What it sounds like is that you are saying the child coming into existence benefits others and is therefore of instrumental use or a means to an end. I don’t actually see the connection between coming into existence versus not existing at all being an overall benefit to the child as you seem to surmise in your very last sentence. Perhaps, the world (of conscious humans) will be better overall as a result and therefore the already existing child will be better off, but that still isn’t the same as saying a non-existent child would be better off by coming into the world, only that once here, it is in the child’s interest to make it better. Overall, I’d summarize this discussion as concluding that deciding to have a child is ultimately a selfish decision on either the parents’ part or the larger group (community, society, world) in order to benefit themselves. Do you think that is a fair summary and would you agree? Rebecca: That’s a fair summary and yes, I agree with it. Since you’ve touched on selfishness, is having a child ever not selfish? Kyle: Definitely, but I think it’s careful to understand the meaning of selfish in this context, because its opposite does not imply good in this case. Having children for selfish reasons just means that you have them for yourself and not for others. We could definitely have children for altruistic purposes, in that we are having children for the sake of others, while still holding to the idea that having children is no benefit to the child itself, but rather other living humans. Rebecca: Thinking about having children for yourself means talking about the ways adults love children. We love children in the ways that we want to love everyone, but that open, accepting, deep love might be easier with a child. Children, especially young children, are largely devoid of judgment and instead completely accepting of the people around them, which is something that we want with all people in all of our interactions. However, that’s often really difficult to express, unfortunately, and I think there are a lot of sociocultural and perhaps environmental reasons for that. So in this way, having children is a way of loving and being loved in the ways that we truly want to experience. Kyle: I certainly agree. In that sense, having a child is often a “second best option”, meaning we may feel less compelled to have a child for those reasons if we could experience that child-like loving relation with adults. The fact that we can experience it with children almost gets us out of the work necessary to experience it with adults. We can often get quite hurt or rejected by adult relationships in which we open ourselves up and allow ourselves to be vulnerable. After a couple false starts, it can be seen as easier to seek that relation with a newborn than another potentially painful letdown from an adult. In a way, it is throwing in the towel with adult relationships and choosing the easier option. I think this point also connects to some of the reasons parents and children often struggle to have genuine relationships as the children age. A newborn can be loved as an “object of affection”, in which the parents lavish all their uncensored love and wishes on the child. This creates a kind of habit or routine way of interacting with their children that can be hard for parents to change as that object of affection transforms and becomes a subject. It is much more difficult to love a “subject of affection” than an object of affection for the very reason that it (he or she once a subject) can choose to receive or reject that affection, respond or not to that affection, and reciprocate or not that affection. Parents that cannot change their style of loving from that of loving a non-fully conscious object to a fully conscious subject seem to struggle more than others in my experience. These are the parents that you see and hear about that are trying to force their desires and goals onto their children, that love conditionally based on their children’s achievement, and that potentially lose all relations with their children as the children age and decide they no longer wanted to be treated in that manner. Rebecca: That’s a fair assessment. I think you’re right about the need to transition from loving a child as an object of affection to a subject, especially because the hopes, dreams, and desires of all subjects of affection, whether adults or children, need to be valued and considered in any relationship. That’s where, as you say, adult relationships are difficult. They require dialogue and communication that is often unfortunately neglected when we instead develop relationships with children. Having children is potentially good for parents struggling in their own relationships, however, because children provide common ground for experiences, activities, and even hopes and dreams that the parents can share with each other. Ultimately, those parents are probably better off working on their own relationship rather than using children as a way of forming a better relationship with each other. In my experience, it’s rather common for couples to end marriages after their children, those subjects or objects of affection, have developed into autonomous individuals who may not fulfill the same need for their parents as they once did. The relationship has changed. Even though we know that having children is a huge decision, and not only because it completely changes adult relationships, we still expect that young couples want to have children and will choose to do so sooner rather than later. We have clearly been socialized into these beliefs. I don’t think most people want to think about having children as the “default” action, usually after marriage, but it seems to be that way. Why the emphasis on having children and being parents? Kyle: The obvious answer is clearly that it is for species survival and we have powerful biological drives to do so. This is not a satisfying answer to me though because we have strong, powerful urges to do lots of things as a result of our biology. For one, I would classify the urge to sexually assault in any and all capacities, including rape, to be a powerful urge that many or even most men feel as a result of biology and the drive to reproduce and propagate their genes in offspring. But. That is no longer the default mode of action or seen as acceptable behavior and has dramatic consequences because we have all used reason and empathy to understand that it hurts others after some reflection. This reflection now happens at both the individual level and societal level. That is exactly what I think needs to happen now. People should be using reason, empathy, and reflection to proactively decide to have kids or not. Continuing to have kids by default is not a responsible choice. Yes, it is the status quo. And yes, society does exert huge pressures. Particularly on married couples and women more specifically, but that is not a valid or good reason to have children. Instead, we should focus on all three levels of people involved in our decision. The best interests of the future child, our spouse or partner if they will be involved, and society or humanity at large. We’ve already covered the idea that the best interest of the child is simply not to exist at all and that the best interest of the partner or spouse will be dependent on them and you in the relationship you have together. Some people feel they simply can’t live a rewarding and fulfilling life without children and for them, having a child is an act of “self-care”. That is probably fine or okay when both parents go into the decision recognizing the reasons for it and not under false beliefs about what they are doing and why. Last, and I would say most importantly, is the impact on society and humanity at large the decision to have children has. The two biggest impacts for me are that having a child is the single largest addition to your carbon footprint you will ever have direct control over and, even more importantly, the amount of money it costs to raise a child in the developed world can be better spent helping hundreds or thousands of people in the developing world, many of whom already have children that exist and whom they deeply care about and would be heartbroken to lose due to preventable causes like malaria, TB, HIV, hunger, dehydration, etc. and which my money can go towards alleviating. Rebecca: Definitely important to consider society and humanity in the context of this discussion. I think it’s an appropriate time to note that neither of us have children, though I hope to eventually. I don’t disagree that the amount of money it could cost to raise a child in the developed world is badly needed elsewhere and would have incredibly positive impacts on the lives of people in developing countries. At the same time, though, I see it as partially my responsibility, as someone who cares about the world and improving the world, to have children in order to develop more people who care about the world and who will work to create a better and more peaceful world for all those who inhabit it. As an educator, I have some ability to develop such individuals, but there’s definitely more I could do with my own children than others’ children, particularly because a teacher’s direct influence is often only a year long. Parenting lasts a lifetime. It’s important to me to continue impacting the world in positive ways and I think having a child, for me, is a way to do that. Of course, there are all sorts of parenting implications and discussions to consider, but having children in order to create a better world is a deliberate reason to have children rather than a default response to social pressure and cultural attitudes. Kyle: I think this is the argument I am most open to be persuaded by, especially as mentioned earlier if the decision is discussed openly between both parents (or reasonably reflected on by a single parent) and agreed on beforehand. The biggest issue here is simply using the child as a means to an end, also mentioned above. This is no small matter. Many people, good reasonable people at that, could find this abhorrent. I personally do not, but there will be much disagreement on this line of reasoning among rational people and it really does seem to be the only rational reason for having children that isn’t selfish or simply a parental need for a fulfilling life. So while I would be open to persuasion on from this argument by my own wife (or even the personal need argument at the end of the day), I do think it’s worth mentioning and thinking heavily about expected outcomes here. We have a very reasonable idea of what money can do to benefit people who alive now when donated to effective charities and NGOs. Deciding to have children and raise them to benefit the world may or may not be as reasonably expected depending on parental circumstances. I do think, that as you said, being an educator who thinks and learns about ways of making the world a better, more peaceful place does give someone in your particular situation a very likely chance of cultivating a child who could impact the world in immensely positive ways. However, they would need to impact it more than your potential donations would impact it, which is a large task. Furthermore, there is always the chance that your child could be born with genetic abnormalities that lead to disease, disability, early death, or even psychopathic tendencies that research shows afflict about one percent of the population on average. They could also be a perfectly healthy, normal, and capable child who grows up to the age of 21, graduates university having received hundreds of thousands of dollars in your support, only to be hit by a drunk driver the next day and die before being able to return the time, energy, and finances you essentially invested in them as a future world impactor. There are simply a number of unknowns and uncertainties that could potentially happen even if you are perfectly capable of raising such a child and instilling humanistic and altruistic attitudes and dispositions in them. I guess what this is getting at is risk aversion. I feel open and accepting of your argument, but feel your “entrepreneurial attitude” as it were is perhaps too optimistic compared to the safe and near certain prospect of charitable donation and immediate alleviation of suffering today versus two decades from now. Rebecca: I can agree with your point about optimism. There are, of course, a whole number of “what ifs” and “maybes” involved in any major decision like this. There is a lot of uncertainty. I understand and accept that. There’s an element of the “self-care” argument that you mentioned above involved in my thinking, too. The most important aspect of the decision for me, though, is that it is an actual decision. It’s a choice. Your choice not to have children, or to later be persuaded by one argument or another, is an active decision to do X rather than Y. We are both looking at this question with a real consideration for humanity as a whole. The world can benefit from charitable donations to a wide range of causes, but also from the cultivation and development of people who aim to improve the world. That’s the job of both educators and parents. My goals as an educator are to help children grow into people who work to benefit those around them and increase their well-being; the goal is the same when I consider being a parent. I personally have a difficult time separating my overall professional goals from any other decisions I can make, especially when humanity is concerned. Having children and raising them in this way certainly does not excuse me from donating money to NGOs or organizations that can make a tangible impact now, today. This is not a case of choosing one over the other as much as it is a case of choosing both, to the extent that anyone can. I am less able to donate money in choosing to raise children simply because of the cost of raising children, but the impact on the world that any child has the potential to make could be extraordinary. Basing a decision to have children on potential impact, rather than the guarantees that we might see elsewhere, does relate to your point about using children as a means to an end. However, it also makes sense to me in terms of an overarching goal of developing a better, more peaceful world. Kyle: You’ve just touched on balancing between choosing to both have a child and donate, so I can guess at your answers, but I have a couple questions anyway. Given what you just said about the potential for “extraordinary impact” that any child has and a desire to shape children for longer than the one year you often get as a teacher, why not simply invest all your money into having as many children as your finances allow without donating to maximize that extraordinary impact potential or, conversely, have no children at all and invest all your money and time into some kind of experimental school where you could follow the children as teacher from kindergarten through 12th grade and raise anywhere from 10 to 40 children in the process in some sort of cohort type model? Rebecca: I’m most intrigued by the second idea, so I’ll address that first. I would love to be part of an experimental school like that. However, I definitely don’t have the investment capital right now to fund such a project. By the time I do have that capital, I’m not likely to be a teacher any more! To the first point, there’s the necessity of balance. I don’t think having as many children as possible allows you to be as good of a parent as you would be with fewer children. Kyle: That seems sensible. I guess in the spirit of bringing this to a close, I can only think of a couple of other things to talk about. The study of happiness or well-being is getting better and better over time. Quite a bit of research reliably shows that parents are less happy on average than non-parents, but married people are more happy than non-married people on average. Do you have any thoughts on this type of research in regards to deciding on kids once married? Rebecca: I think quite a bit of it has to do with socialization, which I mentioned earlier. We have a view of what we’re expected to do from an early age and that influences the way that we view ourselves. For many people, marriage, home ownership, and having children are probably a very large part of their self-concept. Research also shows that we need congruence between self-concept and our actions in order to feel truly satisfied in our lives. We can also talk about the aspects of our lives that incentivize having children. Single-family homes are deliberately designed and marketed with families in mind. Even though we desperately need to modernize our view of what constitutes family, I expect most people still carry an image of mother, father, two kids, and a dog. Governments provide tax breaks for having children. Restaurant menus, museum admissions, and movie theatres are all very responsive to a highly traditional idea of family, which means it is part of our lives everywhere we turn. I think it’s easy for people to see themselves and their goals in terms of fitting into a world designed like that, and so they have children without thinking about it any further. Kyle: Yeah, exactly. It’s my hope people start to think about that stance beyond their own decision as well. It’d be nice to see things like children being incentivized by government programs looked at quite hard. One easy solution to the falling numbers of a nation-state’s population if you take away incentives to have kids is to allow more immigration for people who want to come to a country like the United States. That seems like a “no brainer” to me for a number of reasons. World GDP is estimated to benefit from more migration of human labor than capital and that is no trifling sum. Being an expat worker for much of my adult life who has moved simply to get a better quality of life, it is easy to understand from my perspective that most people want the same thing. Many families with young children and without would happily move to the developed world to fill the population gap that would be created and bring with them revitalizing ideas and economic growth. It essentially lowers the population at the same time that GDP increases, leading to a massive gain in world GDP per capita. Anyway, that is getting slightly down a different path, but the point is that the way our states and governments are organized assume that having children is the correct decision for most families. This non-critically established belief may not turn out to be true if some of the points in this dialogue are taken seriously, so the issue to have a child is not just an individual parent’s or parents’ problem, but a state and world problem as well. In summarizing my viewpoints on this, coming into existence isn’t a benefit to the actual future child, so we are doing them no favors. The parents themselves could be better off through greater life satisfaction due to a sense of congruence that is almost certainly socioculturally created and socialized into us. They will experience less positive affect on average day to day as research shows and could possibly feel greater overall connection in their lives through their relationships with their children, however, that could be at the detriment of more meaningful and deeper adult connection as we looked at earlier. Finally, the world could be better off or not depending on unknown and uncertain variables. I would say the facts point to large, certain benefits to the world if we choose not to have children and also reevaluate certain legal, political, and social pressures, but agree that we could also produce benevolent, impactful, and world changing children if that was indeed our goal as parents and something we legitimately worked hard to achieve. Anything you want to add or summarize in closing? Rebecca: Your summary provides an accurate picture of my thoughts, as well. The take-home message from this conversation for me has been the importance of truly evaluating our goals and the ways we try to achieve them, especially when deciding to bring another person into this world (or not). I hope that we begin to see a lot more authentic thinking, communication, and dialogue within society about such an important decision as we work towards developing a better, more peaceful world. Further Reading The Age of Sustainable Development Altruism Better Never to Have Been Caring Doing Good Better Grit and Authenticity Money, marriage, kids Practical steps for self-care A Primer in Positive Psychology The Psychology of Desire Strangers Drowning Thanks for reading. If you found it helpful in deciding to have children of your own (or not), please do leave a comment below and consider purchasing the Kindle version for $2.99 to show support.

0 Comments

Done is often better than perfect.

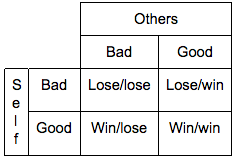

At any given time in our lives, we have one or two things that would be the most effective use of our time and abilities. Of course, this is always relative to our goals and desires. In order to be doing our “best”, we need to have a goal in mind first. This is extremely important to understand in achievement oriented spheres of life like school and work. For example, as teacher, the most important thing to focus on, generally speaking, is the teaching and learning provided to students. I’m still not entirely sure why teaching gets lumped in there, as student learning is probably sufficient. This means that any of the work we do as teachers is by its nature “most effective” when helping students to learn. Other work is acting less effectively. Within any day, we have about eight hours at work and about 16 hours of waking time. We can use that to do our “best” work relative to helping students learn more or better, either now or in the future. Work that doesn’t meet this aim is not our best work. If you follow to this point and agree, then all we have to do is apply the economics idea of opportunity cost. This says that as we expend our energies on one thing, by default we cannot spend those same energies on another thing. This is very important to understand. A few tasks common to the teaching profession include entering grades into some kind of markbook, writing student comments on a quarterly report, or creating units in some sort of computer program that administrators can see and overview. Some of this helps students to learn more or better in the present or future, but many would agree that not all of it does nor that even most of it does. As soon as we recognize that fact, that whatever work we are doing can be contributing to student learning or not, we should immediately go into one of two modes. What Barry Schwartz refers to as “satisficing” or “maximizing”.1 Satisficing is doing the minimum required to get the job done, whether buying a product in the store without comparing online for hours ahead of time or in this case updating grades in a markbook quickly without much thought. Maximizing is the opposite. Spending as much time as possible or needed to perfect the choice or product you are working on. Doing this too often can detract from your other work and Barry Schwartz actually believes that satisficing is the “maximizing strategy” overall. This means being very careful in what we decide to apply maximizing behavior towards. Anytime I hear someone say, and my father is the worst offender I have ever known, “That anything worth doing is worth doing well,” I immediately recognize that person as ignorant of the concept of scarcity as it relates to time and energy and the necessity to make decisions in how we utilize those two resources. We can’t do and be all things to all people. Many of us can’t even reply to every email that comes across our inboxes and this strategy would imply that we not feel an overwhelming need to do so.2 Choices always have to be made. Choose better. That means choosing intelligently. That means choosing with a goal in mind and marshalling all your resources and abilities to do achieve the goal and batching the rest of life into the “satisficers” box to be done with the minimum of effort and distraction as possible. Only then will we have more time to attack the things that really matter to us in life. Notes When push comes to shove, how do we choose who wins and who loses in our decision making process between self and others? Our lives are a tension between negotiation and competition. Most of us have allegiance to both. We say, "Let the best plan for all of us win" (Negotiation), and "it better be mine." (Competition). These three paragraphs had me reflecting on this process and one of the solutions I’ve come up with this year, even if I haven’t actually implemented it with anyone. It involves a simple two by two matrix with both good and bad consequences potentially happening for the self or others when making a decision. From the above, there are obvious decisions that shouldn’t be made. Those are decisions where both self and others are worse off as a result, the “lose/lose” box. Then there are decisions where it is obvious that we should decide in favor of something, the ones in which both self and others win, the bottom right box above.

However, there are still two boxes where self and other are at odds and this is exactly what the opening three paragraphs was discussing as to a time when we need to enter negotiation. I have not used that term myself (negotiation that is), but have come pretty close and so it made intuitive sense to me. Instead, I’ve focused on the word dialogue and also using a rudimentary and hypothetical utilitarian system in order to reach a decision. A Solution That hypothetical system would work something like this. Let’s say a decision can have an impact on my “well-being continuum”, which runs from negative 10 to positive 10, with negative 10 being the worse suffering and positive 10 being a state of bliss, nirvana, etc. For the math inclined, that is -10 ≤ x ≤ 10. One theoretical way to work out decisions when only two people are involved within the “win/lose” boxes is to have both parties give a subjective rating of how a decision would impact their well-being continuum. If party A believes the decision will give them positive 6 points on the continuum, while party B believes it will give them negative 2 points on their continuum, then I say the two people should agree to favor party A. Obviously, this would work in the opposite direction as well. This system has a few obvious flaws. One, people are proven to be very poor at estimating how much happiness or suffering any given decision will bring them.2 Two, it requires genuine dialogue, reflection, and honesty on both parties’ account, a difficult task for even the closest of people. And third, it becomes more and more unwieldy the more parties participate in it. At some point, it is probably better to just turn to regular ol’ run of the mill democracy and take a vote. The benefit a system like this would provide is the basis for caring, open, and rational deliberation on decisions where not everyone will win and the recognition that both parties are not winning. That recognition, that not everyone benefits from all decisions, is itself a valuable insight for many situations that can lead to a deeper sense of caring and reciprocity on everyone’s part. It even has the potential to promote appeasing others as the benefit becomes more and more clear through practice and awareness. It is much easier to accept a “loss” or even prefer it when you receive the pleasure of knowing just how much the other is benefitting and how little you are giving up in return. “The best prevention is awareness, a keen understanding of the human condition and how it plays out in us all. It is through facing the darkness in ourselves that we can shed greater light within and around us.”1 References  I listened to science and experienced more unhappiness in return. Perhaps it is an issue of individual differences. Perhaps it is an issue with averages. I don’t know. I exercise regularly. I eat okay. I have friends I can call in the middle of the night. I work in a field that lets me help others. I focus on accumulating experiences over things. I generally sleep pretty well. I live an examined life with reflection and critical interpretations of my values and beliefs. I forgive and forget very easily. I’m autonomous, competent, secure, and have high self-esteem. I’ve carefully selected aims, goals, and purposes in my life. I’m relatively accomplished and well off. I’m able to change several aspects of myself when I see they are impacting me negatively and also resist and try to change others when I see what I believe is harm they are causing others. Yet, I hate everything at the moment. Everyone is irritating me. Things are irritating me. I’m very irritable. Why is this? I can’t figure it out. That irritates me too. My brain isn’t doing its job. Stupid brain. I’m sitting on the subway. On my way to work. I’m filled with anger and aggression for the third time this week. I sit among strangers, but wish to stand and run, hit, kick, and scream. Anything that will release the flood of bottled up visceral energy coursing through me at the moment. It’s 7:30 am when all this happens. I won’t be home until 5:00 pm at the earliest. Nine and a half hours to go before I have a chance of releasing it in anyway. My old friend science gives more recommendations. Always ready to offer advice. “Releasing anger and aggression through acts of catharsis show adverse effects. Fortunately, there are a number of strategies that can be effective in controlling aggressive desires. These include bolstering self-control capacity through training, by consuming glucose, by empathizing with the person who triggered the desire for revenge, by distracting oneself, and by reappraising provocations.”1 Sounds like a life of distraction might be the best option. What life isn’t one of distraction? Thanks for the suggestion science. This anger and aggression only makes sense through a focus on well-being and happiness as an aim in life. Not everyone outside of science cherishes those aims. “‘Wretched contentment, happiness as peace of soul, virtue, comfort, Anglo-angelic shopkeeperdom a la Spencer’ was for the masses, for the ordinary people, who didn’t matter. The pursuit of happiness, either for oneself or for others, was a contemptible way to spend one’s time, because nobility could be achieved only through suffering. Happiness was not interesting: human greatness should be the goal of life.”2 So thought Nietzsche. He gives some hints as to what human greatness might be. “Nietzsche's positive evaluative ideal of greatness for a human being offers as a highest ideal the capacity to affirm one's life to the fullest extent possible, as tested by the thought experiment of the ‘eternal recurrence’. On the other hand, Nietzsche sometimes talks of greatness in terms of properties of, and relations between a human being's drives or instincts: necessary conditions for greatness include the strength of drives, their multiplicity, and their being in conflict but held in a unity.”3 I’ll keep looking, but he wins for now. He won on my last post about suffering as well. More questions exist though. Does wishing to re-experience one’s life in its entirety make one great? That seems like a weak explanation for someone that valued strength so much. And to what extent is that connected to an early self-inflicted end? Could one wish to live their life eternally the same while also ending it prematurely and simply accept that as part of the life to be relived forever? I listened to a guest speaker give the commencement address to the graduating seniors at a high school yesterday. She was given the honor of center stage and the time, space, and opportunity to inspire them at a unique transition point in their lives. With that experience still fresh, I’ve been reflecting on how we choose to inspire students.

The messages we choose to endorse are important. The people we prop up as aspirational are important. We need to choose better. The lessons delivered by the guest speaker yesterday were far from what I would hope the seniors choose to adopt as their own as they leave high school and begin to develop independence and build the lives they want to live. She spoke of personal achievement through individual determination that resulted in little to no positive impact on the wider world after years of hard work and a small fortune being spent in the process. These are not the results or aims I wish for any of my students or the next generation. Instead, the development of a vaccine, alleviation of hunger, prevention of poverty, and ever greater social inclusion are aspirations worthy of their time, dedication, and finances. Those are accomplishments that should be discussed and provided as inspiration to a graduating senior class. Finding a speaker to address these topics would not be difficult. We would look for someone who has worked in cooperation with others for the betterment of others over a long career that took perseverance and continual decisions to wade through difficulty instead of opting for something easier. These types of stories can be found among scientists, business owners, and leaders of NGO’s and policy workers. The exact organization or topic is not nearly as important as the value the speaker places on altruism, compassion, and protecting and helping those that cannot protect or help themselves. Granted, the values in this post come from a specific orientation and philosophical framework. I currently work at an IB school. The central component of the IB mission statement is to “make the world a better, more peaceful place”. It espouses an “ethic of care” and believes that is the foundation for learning in its school. Much of the IB’s philosophy overlaps greatly with modern educational philosophers such as Nel Noddings and an ever growing body of work in positive psychology and neuroscience that shows our greatest endowments as humans are those connected to imagination, cooperation, and the resulting empathy and compassion for others. While modernization and industrialization granted us the largest leaps in quality of life the world has ever seen, it will only be through a postmodern or postindustrial reevaluation of what matters that will allow the current generation still in development to deal with and solve the many global issues that have resulted and continue to persist. In order to do that, schools such as the one I currently work at need to be hyper conscious of the messages, signals, and lessons they give to students. Especially the last one they receive at an event like their graduation ceremony. “Let’s save 1,000 lives.”

“That’s cliche.” “Let’s focus on well-being and suffering.” “That’s cliche.” Why do those statements come across that way? It seems as much as we want to be happy, people have a genuine aversion to actually focusing on it. To say, “I’m hurting,” is to admit something dirty or weak. Especially when nothing is obviously wrong. To be privileged is to lose any reason to suffer. This seems ignorant and misinformed. Suffering is an internal state, not necessarily connected to one’s own external circumstances. The fact is, the better my external circumstances get, the more acutely I feel the disconnect between me and “them”. Them being people all around the world who have to watch their children die in front of them because they don’t have a few dollars to spare for water, food, or medicine. It is a tragedy. One that should cause everyone in the “first world” to walk around in a constant state of acute pain. Yet we don’t. Only another reason to feel pain and suffering. The lack of empathy from the developed world is itself a reason for despair. How can we all be so comfortable in our extravagance. We sit on plush leather sofas in air conditioned mansions as single room brick houses literally fall down around people in places like Kathmandu. “I don’t need anything at all. Donate money to Against Malaria if you want to do something for me.” “I can’t do that, it’s not the same. I want to give you something, not some distant person unconnected from me.” The above was a short conversation with the person who should be closest to me in the entire world. Who should love me unconditionally and wish to fulfill all my wishes. Her two children take several trips a year to developing countries, one as a surgical nurse and the other as an educator. Our lives have no effect on her spending decisions when it comes to gifts. She continues to spend on us, two working professionals with salaries and no kids, debt, or health problems. How do you change others when you can’t change a person that has loved you since birth? And by writing these lines, I know she will be pained herself. More suffering. I’ve hurt her with no intention. She’s hurt me with no intention but to show love through giving. These small episodes mount and grow. Over time they result in depression. A constant sucking of optimism and hope. The lessening of zest and zeal. James Altucher writes, “You have to bleed so much in every post that your superficial “you” is scared. The intuitive, internal “you” that’s in touch with this creative source knows what the right thing to write is and what the right thing to bleed is.” I’m “bleeding” left, right, and center. It’s going out faster than it’s coming in. My “superficial me is scared” because most will interpret this wrong. They might reach out to help. Worried that something is wrong. This is not a call to help me. It is a call to help anyone in need. Open up. Share. Connect. Listen. Help others who are hurting. Stop blaming, guilting, assigning responsibility, expecting, and shaming. No one “deserves” it. Whatever it is. Be. Connect. Love. Help. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed