"The ultimate purpose of economics is to understand and promote the enhancement of well-being." - Ben Bernanke Economics is often described as the study of scarcity or the study of decision making, which is a result of scarcity. If we have scarce time, money, or resources, we must choose how to allocate and use them by making some decision on what we do. Decision making is assumed to be done by rational agents who wish to maximize what economists call “utility”, which is really just a fancy word for satisfaction, happiness, or well-being. Understanding that economics is simply the study of how we maximize our happiness by making better decisions lets us see how several important concepts interact. Consumption The term consumption is often tied to expenditure in economics, i.e. spending money on goods or services. However, consumption can actually be thought of as using resources to gain utility. This fundamentally results in consumption being just another proxy, albeit an incomplete one, for happiness. By using resources, humans attempt to gain utility and therefore increase their well-being. Use of resources in consumption isn’t the only way we gain well-being, but is a large piece and the piece economics has traditionally focused on. Because the bulk of economics studies resource accumulation and allocation, economists sometimes confuse consumption of these resources with the main, or even only, source of well-being. That is clearly not true from any half-hearted skimming of the research from fields like positive psychology, philosophy, and history (see links at the end of this article for further reading). However, if we limit our view of well-being to consumption, economists have recently started asking just how best to consume for maximization of well-being. One source, Happy Money, lists five ways to consume for maximal well-being by researching the topic and recommending that you spend money on:

If consumption is undertaken to provide well-being, the above five uses will get you the most bang for your buck. Investment The best way to frame investment within the perspective we are taking here is to think of it as future consumption. You delay the act of using up resources in today’s consumption by instead saving and then allocating those savings to channels which are likely to be worth more in the future. This delaying of today’s consumption allows one to consume more in the future. If we are able to recognize the above, it is not difficult to then see that: Investment = future consumption = future well-being We should therefore allocate our savings to investment channels which we believe will be worth more in the future and thereby enhance our future well-being by expanding our consumption options. Typical examples and channels for investment include business, securities, property, infrastructure, and education. Figuring out just what channel will maximize returns into the future is obviously dependent on preferences, risk tolerance, and a lot of luck, but the goal is the same - future consumption as a proxy for well-being. Credit and Debt These two concepts are closely related, but serve the same purpose. Credit, properly used, allows people to smooth consumption over their lifetimes. When we are young, we typically have very little income and wealth and cannot consume much as a result, even if we have high needs. When we are old, we typically have lots of income and wealth (relative to our youth), but less need to consume. By utilizing credit, a person can take on debt to pay for today’s consumption while postponing payment until later. Essentially, credit is equivalent to consuming today and paying tomorrow. Understood in this way, credit and debt are two of humanity's best inventions. Rather than be forced to go on a “low consumption diet” when young and live with a large surplus of unneeded consumption in old age, we can simply smooth our consumption curves by consuming on the basis of credit and debt while young and knowing that we will be able to use our old age surplus to pay for it. This does have a natural consequence that should be clearly noted. If we take on debt by using credit to consume without ever increasing our earnings potential, we will not actually be richer in our old age. This means that the debt we take on as young people ought to be focused mainly on the investment channels described above: business, property, and education. By focusing on these channels when taking on debt, we make it much more likely that we will in fact be richer in the future and more able to pay back the debt we’ve taken on today. Ideally, one would invest in education while young, using debt if necessary, and then move on to start new businesses or gain employment in established businesses, before investing savings into channels like property and securities, which themselves act as vehicles for long-term savings. Sustainability If consumption, investment, credit, and debt are really just concepts that act as proxies for the management of well-being, then sustainability can properly be thought of as “future happiness”, not too unlike investment. This takes a little bit of explaining. Sustainability is often discussed in terms of stocks and flows, which are most easily illustrated with the image of a sink containing a given water level that is affected by a drain with water exiting the bottom and a tap with water entering the basin from the top. The water that already exists in the sink is the stock, while the water flowing out and in via the drain and tap are the flows. To maintain the same stock in the sink, the rate of outflows and inflows need to match each other. If the outflow is greater than the inflow, the stock will deplete over time. If the inflow is greater than the outflow, the stock with increase over time.

Sustainability is therefore the management of the stock level for given needs over a given time. In the case of a single person planning for their own life and retirement, sustainability is managing one’s savings so that they run out when the person’s life runs out. If we begin retirement with one million dollars in savings (stock) and plan to live for 20 years without new income (inflow), we can’t simply spend $100,000 each year (outflow) or we will run out in ten years. The outflow is not sustainable. The stock (savings) will be depleted through the outflow (spending) with no new inflows (income) before the person dies. In the case of humanity as whole, we aren’t worried about the savings and spending of a single retiree, but the world savings (all natural resources) and world consumption (total GDP). We can choose to deplete our stock of natural resources today, by consuming at a rapid pace, but this will have effects on what stock is left to posterity. If the stock goes to zero, because of poor management, it will be very difficult to enjoy the future. That’s because for all the limitations of using consumption as a proxy for happiness, one thing is clear, Kanye West was correct when he rapped, “Havin' money's not everything, not havin' it is”. Said differently, having infinite resources may not make us infinitely happy, but having no resources will make us infinitely unhappy. So as stated above, sustainability is really just future happiness that results from proper management of our resources today so that they are available for use in the future. A Model This all points to a model for living based on individuals maximizing well-being while simultaneously being mindful of others’ well-being. As individuals we want to consider maximization of well-being as an intra-relational, inter-relational, and temporal problem, meaning that how to maximize well-being for an individual will be a result of internal desire and goal states (intra-relational), our external relationships with others (inter-relational), and the balance of today’s and tomorrow’s (temporal) well-being in relation to both ourselves and others. I’ve written extensively on the first two problems already. See The Well-being Algorithm for a description of the intra-relational problem. See Be Happy or Be Good?, Having Children, Deciding Who Loses, The Communication Market: Speaking Honestly, Lies, or Not at All, Acceptance and Tolerable versus Intolerable Harm, The Future of Work, Why I Don't "Like" Adoption, Prioritizing World Problems, and A Trump Presidency Will Kill Thousands, Possibly Millions for discussions of the inter-relational problem. I’ve also written a bit about the temporal problem. See Why You Need Stress, The Exercise Algorithm, The Feudalism of America Today, The Education Algorithm, and F*ckin' Baby Boomers: Some Good Paragraphs about Them. All of these previous writings have in one way or another highlighted areas where tradeoffs and conflicts exist, either between our own desires and goals, our own well-being and that of others, or between today and tomorrow’s level of well-being. This article is attempt to add to these previous discussions and elaborate on how the often abstract, everyday economics we see in the news relates to well-being in reality. How we choose to consume, invest, use credit and debt, and manage issues of sustainability matter. They matter to us, both today and tomorrow. They matter to others, both those alive today and those alive tomorrow. Ultimately economics is the field of study that attempts to figure out all of these trade-offs and the consequences we face for whatever decision we eventually make. Seeing, knowing, and recognizing that these decisions aren’t really about money or profit and loss, but real people’s lives and real people’s well-being helps us decide what really matters and allows us to act accordingly.

1 Comment

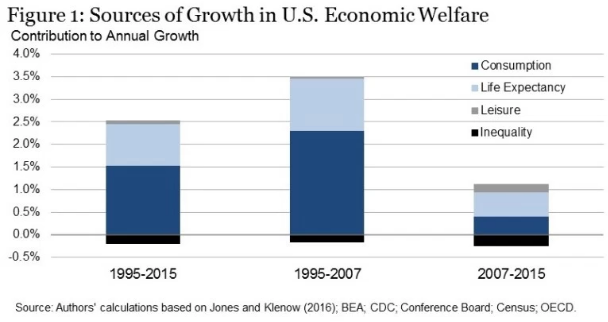

According to Ben Bernanke and Peter Olsen at The Brookings Institution,

Economically speaking, are we better off than we were ten years ago? Twenty years ago? When asked such questions, Americans seem undecided, almost schizophrenic, with large majorities saying the country is heading “in the wrong direction,” even as they tell pollsters that they are optimistic about their personal financial situations and the medium-term economic outlook. While thinking about the question, we came across a recently published article by Charles Jones and Peter Klenow, which proposes an interesting new measure of economic welfare. While by no means perfect, it is considerably more comprehensive than median income, taking into account not only growth in per capita consumption but also changes in working time, life expectancy, and inequality. Moreover, as the authors demonstrate, it can be used to assess economic performance both across countries and over time. In this post we’ll report some of their results, and extend part of their analysis (which ends before the Great Recession) through 2015.[1] The bottom line: According to this metric, Americans enjoy a high level of economic welfare relative to most other countries, and the level of Americans’ well-being has continued to improve over the past few decades despite the severe disruptions of the last one. This couldn’t be any clearer. America does not need to be made great again. It is still great, by nearly all measures of economic welfare and getting better. The article ends with an additional caveat that tips even further in favor of increased prosperity, Methodologically, the lesson from Jones and Klenow’s research is that economic welfare is multi-dimensional. Their approach is flexible enough that in principle other important quality-of-life changes could be incorporated—for example, the 63% decrease in total emissions of six of the most common pollutants from 1980 to 2014 and the decline in crime rates. We need better measures of how well Americans are being served by the economy, and frameworks such as this one are a promising direction. Do read the whole article for more insight and numbers. According to David Graeber in his fantastic book Debt: The First 5,000 Years,

The definitive anthropological work on barter, by Caroline Humphrey, of Cambridge, could not be more definitive in its conclusions: “No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing.” (Kindle Locations 662-664) He continues to describe the “myth of barter” as one of the largest fallacies in economics. He then points out all kinds of interesting connections between the concept of debt and how we treat others and view human nature. More particularly, he examines how debt is closely tied to guilt and has often been used throughout history to control and punish people, often very cruelly, with the moral justification that debtors owe their creditors and society more broadly. If one were looking for the ethos for an individualistic society such as our own, one way to do it might well be to say: we all owe an infinite debt to humanity, society, nature, or the cosmos (however one prefers to frame it), but no one else could possibly tell us how we are to pay it. This at least would be intellectually consistent. If so, it would actually be possible to see almost all systems of established authority— religion, morality, politics, economics, and the criminal-justice system— as so many different fraudulent ways to presume to calculate what cannot be calculated, to claim the authority to tell us how some aspect of that unlimited debt ought to be repaid. Human freedom would then be our ability to decide for ourselves how we want to do so. No one, to my knowledge, has ever taken this approach. Instead, theories of existential debt always end up becoming ways of justifying— or laying claim to— structures of authority. The case of the Hindu intellectual tradition is telling here. The debt to humanity appears only in a few early texts and is quickly forgotten. Almost all later Hindu commentators ignore it and instead put their emphasis on a man’s debt to his father. (Kindle Locations 1453-1462). I have to admit that I have always found the language of debts owed to be rather ugly and disgusting, so this language appeals to me. I generally don’t think of it in terms of money, but moreso the existential debt he describes. This often bleeds into every interaction and relationship we have with others, particularly those who claim to be closest and most caring to us. How often do we owe our parents, family, and friends for past “gifts”? How often do we owe our partner, girlfriend, boyfriend, fiance, or spouse? How often do we feel we owe our employer, city, state, or nation? We do not owe them for the past or present. We were not asked about whether we wished to come into existence and we often do not ask for the gifts “freely” given to us. To expect an IOU in return for receiving these “gifts” is, as I said above, ugly and disgusting. Give freely or don’t give at all, but don’t expect a debt in return either way. Below is everything I’ve read this past week. The books may have been started in previous weeks, but were finished in the previous seven days. Most of my reading relates to education for sustainable development (Edu21). Books Articles and Videos

I’m currently reading John Kay’s book Other People’s Money: The Real Business of Finance. So far it has been great, even if a little dense and slow going. I found these paragraphs particularly good:

The individualistic ethos of the era of financialisation has affected wealth transfer over time in other ways. The American economist Laurence Kotlikoff created the concept of ‘intergenerational accounting’ to describe the government’s transfer of wealth over time. 15 The journalist Tom Brokaw coined the phrase ‘the greatest generation’ to describe my parents and their contemporaries, who grew up during the Great Depression, fought in the Second World War and (in Europe) suffered privation in its aftermath. 16 Another author might term my generation of ‘baby boomers’, ‘the luckiest generation’ or perhaps just ‘the most selfish generation’. We have not only been successful— and perhaps this is to our credit— in enjoying a time without major armed conflict or deep economic depression; we have also been effective in transferring wealth from both past and future generations to ourselves. We reduced the debt we owed to our predecessors by rapid inflation. We promised ourselves generous state and occupational pensions, and then argued that the burden of providing them for subsequent generations could not be afforded. We sold assets that had been accumulated in the past, and would yield prospective benefits in the future, for our own current benefit, privatising state industries and monetising the goodwill in Goldman Sachs and Halifax Building Society. We let house prices and share prices rise to new highs in real terms, forcing our children to buy the nation’s assets from us at prices much higher than those we had ourselves paid. To add insult to injury, we seem to have been inadequately mindful of the national infrastructure: enjoying shopping malls, to be sure, but building few houses and allowing the transport system to decay. The John Kay of the 1980s, transported twenty-five years forward in time, would not be able to afford to buy the house I still live in, would have incurred substantial debt in higher education, would have to make greater provision for his own retirement and would look ahead to a tax burden inevitably rising to meet the costs of an increasingly adverse demography. When Jeff Skilling toasted the capitalisation of energy contracts in champagne, he was celebrating the twin benefits of the prudence of his predecessors and his own imprudence in relation to his successors. And I could join him in that toast. Lucky indeed to have lived through the era of financialisation. (Kindle Locations 4541-4560) Thanks mom and dad! Hope that champagne tasted good at least. My school recently hosted its parent-teacher conferences for two days and because my classes are grade 11 and 12 students, many parents had questions about planning for university and what I would recommend. I recommend not worrying or thinking about university at all. Do not do anything in high school because you believe it matters for university. I can’t be more clear than that. Let me clarify and stipulate the caveats. American Universities I tell all the parents I speak with that I only know anything about American universities and, really, only California universities in particular. If their goals or desires are to go elsewhere, then it is up to them to inform themselves about what is needed and what stress levels they are willing to take on for the sake of entrance to those other universities. However, once your desire is to go an American university and California more specifically, I strongly believe that we have enough choices, pathways, and opportunities that young people in high school should really stop worrying and stressing themselves to breaking points about which university they will go to. A fairly typical schedule for a high-achieving high school student looks like the below, 6: 15 A.M.: Wake up, get ready for school, and grab a quick breakfast That is nonsense. There is no reason to grind through a day of drudgery like the example above. This is because California has a three tiered public higher education system that includes the California community colleges, the California State University (CSU) system made up of 23 campuses, and the University of California (UC) system comprised of 10 campuses. The majority of high school students can get into a community college with little to nothing in the way of grades, test scores, or even a diploma. Here are the admission requirements from the online admissions portal, California community colleges are required to admit any California resident possessing a high school diploma or equivalent. Additionally, California community colleges may admit any nonresident possessing a high school diploma or equivalent or anyone (resident or nonresident) over the age of 18 without a high school diploma or equivalent who, in the judgment of the board, is capable of profiting from the instruction offered (my emphasis added). These colleges allow students to complete the first two years of university and then transfer to a four-year institution, such as the CSU and UC systems mentioned above. Many of these campuses have preferential transfer agreements that take the community college graduates first before admitting others to the university. Some even have “transfer admission guarantees”, Six UC campuses offer the Transfer Admission Guarantee (TAG) program for California community college students who meet specific requirements. You Have a Choice All of the above means you have a choice as both a student or a parent. You can kill yourselves trying to earn a perfect 4.0 GPA or even higher to get into schools like UC Irvine as a freshman or you can attempt to enjoy the high school experience. Choose classes you have interests in and study what excites you. Don’t take the tests seriously other than as personal insight into how you are doing relative to some external benchmark that may or may not be important to you. Pursue learning for its own sake and develop an innate desire to gain new knowledge and discover new paths to meaning and purpose in your life. The decision to treat high school as an opportunity for relaxed exploration and discovery will go much further than the choice to participate in a rat race of “high achievement” measured by grades in areas that may matter nothing at all to you as an individual. It Doesn’t Matter Where You Start Ultimately it doesn’t matter where you begin higher education after high school. Some evidence even points to the fact that it doesn’t really matter where you end. According to two economists from Princeton and the Mathematica Policy Research, Alan Krueger and Stacy Dale respectively, students, who were accepted into elite schools, but went to less selective institutions, earned salaries just as high as Ivy League grads. For instance, if a teenager gained entry to Harvard, but ended up attending Penn State, his or her salary prospects would be the same. All of this points to the idea that much is determined by the individual student herself and not the institution she eventually attends. However, if the name on the institution does matter to you, it is typically only the last institution you received a degree from that will matter. Beginning at community college before transferring to a CSU to complete your undergraduate degree with a decent GPA and good professor rapport gives one a great opportunity to then apply for a master’s degree at an even more prestigious school. Leveraging that undergraduate experience and degree to get into a master’s program at a UC or elite private school like USC or Stanford will still allow one to claim they went to one of the top universities in the nation. The only difference between taking the path outlined above and leaping straight into an Ivy League or UC is that you won’t have forfeited many happy life years grinding through classes with the sole intent of a better future. You will also have saved thousands of dollars in the process. And when people ask you where you went, you will still be able to answer the name of your dream school because it doesn’t matter where you start, it only matters where you finish and, more importantly, what you do with the education you received along the way. P.S. On a personal note, I went straight into CSU Channel Islands upon graduating high school and attended two different community colleges during summer school in order to complete my BA in economics in three years. I then decided to stay a fourth year to complete a BS in mathematics. After two years working abroad and teaching overseas, I returned to California and applied to master’s programs at the University of Southern California (USC) and the University of San Diego (USD). I was accepted to both and chose to attend USD in order to save money on tuition and rent.

Below is everything I’ve read this past week. The books may have been started in previous weeks, but were finished in the previous seven days. Most of my reading relates to education for sustainable development (Edu21). Books Articles and Videos

It seems even more perspective is needed after the second debate on the magnitude of differences between Clinton and Trump. I’ve already published a curation of the differences in their economic plans and the consequences most likely to occur based on expert analysis. More is needed. I recently published an article that attempted to prioritize and give weight to the largest problems in the world. Admittedly, they aren’t all problems directly affecting the United States citizen who is voting in the upcoming election, but many of the problems do directly affect the average American citizen and all indirectly affect them. In either case, they help to frame and focus the issues that are most important. Here is the executive summary list included in that article: The most pressing issues with highest returns on investment are:

All of the extreme risks from number one apply to the United States and Trump is categorically more dangerous on all accounts. While neither candidate appears to be too worried about threats from superintelligent AI as of now, Trump does not believe climate change is man-made and has repeatedly referred to it as a hoax. In fact, according to Time, “A group of 375 leading scientists, including 30 Nobel laureates, penned a letter criticizing Trump’s stance on climate change earlier this month.” On the other hand, Clinton has publicly stated that climate change is a serious problem and has extensive plans to address it. This is an issue that will greatly affect anyone alive 50 years from now and anyone with kids should be very concerned for the future we are leaving them. To give just one example, if sea levels do rise as a result of global warming there would need to be mass migration from the coasts where 50% of the world lives. The world is currently unable to cope with four million Syrian migrants. What will happen when hundreds of millions of people need to move as climate refugees? That type of movement could result in what Naomi Klein has termed “genocide due to apathy” as potentially millions of climate refugees become stranded in transition. Continuing with number one above, the largest threats involving biosecurity and nuclear security would come from proliferation of weapons that find their way into dangerous hands. Trump has made several comments regarding nuclear weapons and does not seem to have a problem with more countries acquiring them, thereby increasing access among potential threats. For some perspective on just how dangerous either of these issues are, Nate Silver gives some statistical likelihoods given our prior knowledge, A flu strain that was spread as easily as the 2009 version of H1N1, but had the fatality ratio of the 1918 version, would have killed 1.4 million Americans. There are also potential threats from non-influenza viruses like SARS, and even from smallpox, which was eradicated from the world in 1977 but which could potentially be reintroduced into society as a biological weapon by terrorists, potentially killing millions. (p. 229) For nuclear weapons, it gets just as bad, Consider again the case of terror attacks. The September 11 attacks alone killed more people— 2,977, not counting the terrorists— than all other attacks in NATO countries over the thirty-year period between 1979 and 2009 combined (figure 13-7). A single nuclear or biological attack, meanwhile, might dwarf the fatality total of September 11. These are very serious threats and the priority they should be given are much higher than what most members of the public care to think about day to day.

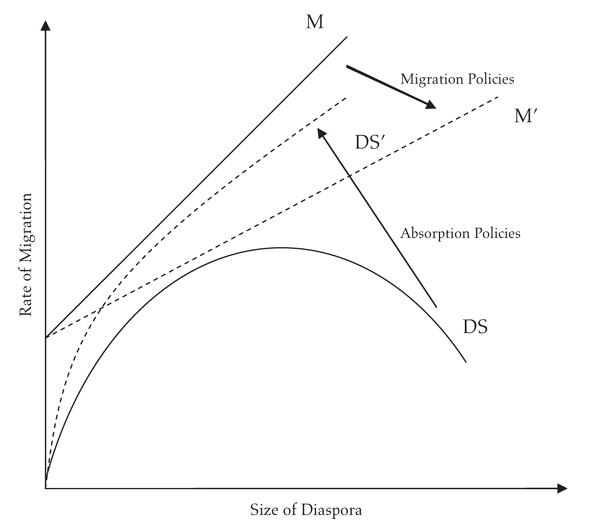

I’ll ignore number two above for now because it doesn’t fit with the message of this article, but needless to say, the elected president ought to spend more time and money dedicated to proactively figuring out which problems should be addressed in regards to allocation of our limited resources. Number three is an issue that I’ve already addressed and Trump comes out much, much worse. You can see the evidence, analysis, and data by looking at my previous post on the subject of their economic plans. To add to the discussion and data in my other article, the idea of millions of Americans potentially losing work and increasing the unemployment rate is a life and death situation. According to a meta-analysis of 42 studies on the topic, “Our findings show that unemployment was associated with an increased relative risk of all-cause mortality. We show that the risk of death was 63% higher among those who experienced unemployment than among those who did not, after adjustment for age and other covariates.” This translates into literally thousands of deaths as a result of Trump’s proposed economic plans. Numbers four through six are mainly aimed at the developing world in regards to how pressing and absent they often are. However, even here we find that Trump wants to make it more difficult for women to make choices about their own bodies and thereby take the opposite approach to what is deemed most effective for health and development. He also wants to do away with the Affordable Care Act and in the process strip 20 million Americans of their health insurance, access they’ve only gained because of its creation. Clinton, again, has plans that would benefit family planning for women and help insure more people for lower costs. On top of this, his education plan endorses school choice, an option that many believe fosters the breakdown of public education as a prized institution by siphoning off dollars and diluting the pool of funds needed within already underfunded schools. It is the exact opposite strategy used by the Finnish school system, which in many respects is regarded as the best system in the world. Whether it is extreme risks, trade and migration reform, family planning, health care, or education, Trump is objectively offering worse plans than Clinton in almost every way. The economy, health care, and education are the issues that most people deal with on a personal level. Many of the other issues are abstract and can’t be directly experienced except in the instance of some terrible tragedy. So even if one is only worried about himself and his family, the three issues of economic prosperity, health care, and education are all better achieved according to expert analysis via the plans proposed by Clinton. There is simply no contest. Electing Trump will directly or indirectly result in literally thousands of deaths, both within and outside of the United States and anyone that votes for him should feel partially responsible those lives. The above diagram shows the interaction of migration rates, diaspora sizes in host countries, and absorption rates of the diaspora into the host country population (i.e. assimilation or integration). The absorption rate can be seen as the changing slope of the diaspora size curve. If the DS curve does not intersect with the migration rate curve, M, then no equilibrium can occur. This means that the diaspora will continue to increase in size as the migration rate accelerates beyond what the absorption rate can handle. All of the above implies we can reach an equilibrium point of intersection by either lowering the M curve or raising the DS curve, i.e. lowering the rate of migration or increasing the rate of absorption from the diaspora into the host population.

According to Paul Collier in Exodus: This recent evidence is a skimpy basis on which to answer what is potentially the most important question on migration. Although migrants themselves do well from migration, it can only be truly significant in addressing hardcore global poverty if it accelerates transformation in countries of origin. In turn, that transformation is at base a political and social, rather than an economic, process. So the potential for migration to affect the political process for those left behind really matters. These studies provide straws in the wind. Political values nest into a larger set of values about relations with other people in society that, as I discussed in part 2, differ markedly between host countries and countries of origin. On average, the social norms of high-income counties are more conducive to prosperity, and so in this restricted but important sense they are superior. After all, it is the prospect of higher income that induces migration. So do functional social norms diffuse back to countries of origin in the same way as norms of democratic political participation? A new study of fertility choices finds precisely this result. Desired family size is one of the stark social differences between rich and poor societies. The experience of living in a high-income society not only reduces the preferred family size of migrants themselves, but feeds back to the attitudes of those back home. Evidently, this benign process of norm transfer depends upon migrants themselves being sufficiently integrated into their host society to absorb the new norms in the first place. (p. 188) The book is full of other examples on how migration affects various stakeholders and is possibly the best read of the year so far in terms of critical thinking based on the best evidence available about an issue of global importance. He finishes with a recommended policy package for ensuring the integration mentioned above does in fact take place and that the social models that create prosperity are not eroded in the process. They include policies aimed at ceilings on the number of migrants, selectivity of said migrants, integration specific policies, and legalizing illegal immigrants under specific conditions. Because I still believe that liberty should rank extremely high as a modern value, ceilings and selectivity policies are practices I’d like to see kept to a bare minimum. But as Collier points out, for any ceiling on diversity, the lower the rate of absorption (i.e. integration) the lower must be migration, so multiculturalism has a clear cost. It is premature to give up on integration. A fit-for-purpose migration policy therefore adopts a range of strategies designed to increase the absorption of diasporas. The government cracks down hard on racism and discrimination on the part of the indigenous population. It adopts Canadian-style policies of requiring geographic dispersion of migrants. It adopts America-in-the-1970s-style policies of integrating schools, imposing a ceiling on the percentage of pupils from diasporas. It requires migrants to learn the indigenous language and provides the resources that make this feasible. It also promotes the symbols and ceremonies of common citizenship. Most people who consider themselves progressive want multiculturalism combined with rapid migration and generous social welfare programs. But some combinations of policy choices may be unsustainable. Electorates have gradually learned to be skeptical of the alluring policy combination of low taxes, high spending, and stable debt offered by rogue politicians. There may, perhaps, be an equivalent impossible trinity arising from the free movement of people. It may prove unsustainable to combine rapid migration with multicultural policies that keep absorption rates low and welfare systems that are generous. The evidence pointing to such an impossible trinity is sketchy, but be wary of outraged dismissals: social scientists are not immune from systematically biased reasoning. (pp. 264-265) The above makes the point that if we wish to maintain social models in high-income nations, there is a limit to the amount of multiculturalism that is sustainable. Beyond a certain point, the multitude of heterogeneous cultures becomes damaging of social capital and mutual regard. That is somewhat ironic as the whole point of coming to the host country was to take advantage of its social model. Still, limiting people’s movements for the sake of others seems overly restrictive and therefore integration needs to be helped as much as possible to allow greater mobility with less erosion of successful social models. The diagram at the top makes it clear that an equilibrium of a migrant population in a host country can be reached by either lowering the migration rate or raising the absorption rate through policy enactment. As one of the progressives Collier mentions above, I'd prefer to see that equilibrium reached by raising the absorption rate instead of restricting the migration rate, but a choice has to be made in either case if we do truly value the social models that have been created within high-income countries. Much of these ideas and facts are touched on in the Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality. I highly recommend it if you are interested in a more thorough textbook explanation of our current understanding of morality and development. The most important thing to realize is that the “continuum of caring” mentioned in the video is a biological fact of our world. Many people will simply find it almost impossible to develop caring to high levels due to their development as a person, whether it be genetic, epigenetic, intrauterine, or cultural pressures that form their worldview and perspectives.

As Marsh states in the video, some research seems to suggest that the mean is shifting toward the right (i.e. the world is getting more moral) on that continuum of caring and that is largely because we are getting wealthier, better educated, and developing more understanding of the aspects that influence the development of altruism, or a concern for the well-being of others. Wealth, education, and greater understanding all work together to allow us to lower stress levels throughout the development process and thereby give us the psychological slack to “turn outward” from a self-interested position of simply surviving to a position of wanting to explore and influence our surroundings in positive ways. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed