|

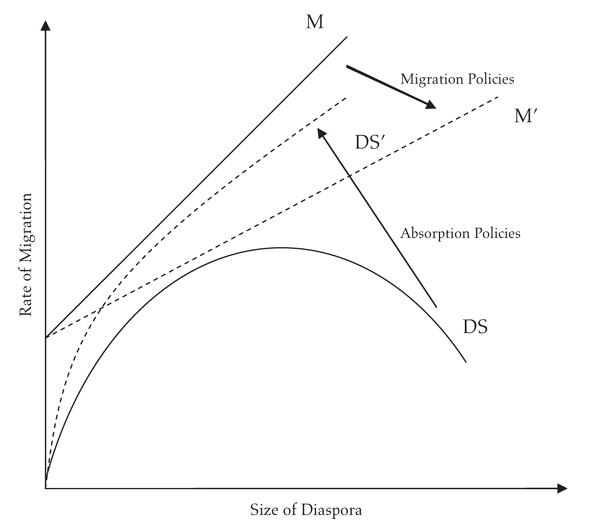

The above diagram shows the interaction of migration rates, diaspora sizes in host countries, and absorption rates of the diaspora into the host country population (i.e. assimilation or integration). The absorption rate can be seen as the changing slope of the diaspora size curve. If the DS curve does not intersect with the migration rate curve, M, then no equilibrium can occur. This means that the diaspora will continue to increase in size as the migration rate accelerates beyond what the absorption rate can handle. All of the above implies we can reach an equilibrium point of intersection by either lowering the M curve or raising the DS curve, i.e. lowering the rate of migration or increasing the rate of absorption from the diaspora into the host population.

According to Paul Collier in Exodus: This recent evidence is a skimpy basis on which to answer what is potentially the most important question on migration. Although migrants themselves do well from migration, it can only be truly significant in addressing hardcore global poverty if it accelerates transformation in countries of origin. In turn, that transformation is at base a political and social, rather than an economic, process. So the potential for migration to affect the political process for those left behind really matters. These studies provide straws in the wind. Political values nest into a larger set of values about relations with other people in society that, as I discussed in part 2, differ markedly between host countries and countries of origin. On average, the social norms of high-income counties are more conducive to prosperity, and so in this restricted but important sense they are superior. After all, it is the prospect of higher income that induces migration. So do functional social norms diffuse back to countries of origin in the same way as norms of democratic political participation? A new study of fertility choices finds precisely this result. Desired family size is one of the stark social differences between rich and poor societies. The experience of living in a high-income society not only reduces the preferred family size of migrants themselves, but feeds back to the attitudes of those back home. Evidently, this benign process of norm transfer depends upon migrants themselves being sufficiently integrated into their host society to absorb the new norms in the first place. (p. 188) The book is full of other examples on how migration affects various stakeholders and is possibly the best read of the year so far in terms of critical thinking based on the best evidence available about an issue of global importance. He finishes with a recommended policy package for ensuring the integration mentioned above does in fact take place and that the social models that create prosperity are not eroded in the process. They include policies aimed at ceilings on the number of migrants, selectivity of said migrants, integration specific policies, and legalizing illegal immigrants under specific conditions. Because I still believe that liberty should rank extremely high as a modern value, ceilings and selectivity policies are practices I’d like to see kept to a bare minimum. But as Collier points out, for any ceiling on diversity, the lower the rate of absorption (i.e. integration) the lower must be migration, so multiculturalism has a clear cost. It is premature to give up on integration. A fit-for-purpose migration policy therefore adopts a range of strategies designed to increase the absorption of diasporas. The government cracks down hard on racism and discrimination on the part of the indigenous population. It adopts Canadian-style policies of requiring geographic dispersion of migrants. It adopts America-in-the-1970s-style policies of integrating schools, imposing a ceiling on the percentage of pupils from diasporas. It requires migrants to learn the indigenous language and provides the resources that make this feasible. It also promotes the symbols and ceremonies of common citizenship. Most people who consider themselves progressive want multiculturalism combined with rapid migration and generous social welfare programs. But some combinations of policy choices may be unsustainable. Electorates have gradually learned to be skeptical of the alluring policy combination of low taxes, high spending, and stable debt offered by rogue politicians. There may, perhaps, be an equivalent impossible trinity arising from the free movement of people. It may prove unsustainable to combine rapid migration with multicultural policies that keep absorption rates low and welfare systems that are generous. The evidence pointing to such an impossible trinity is sketchy, but be wary of outraged dismissals: social scientists are not immune from systematically biased reasoning. (pp. 264-265) The above makes the point that if we wish to maintain social models in high-income nations, there is a limit to the amount of multiculturalism that is sustainable. Beyond a certain point, the multitude of heterogeneous cultures becomes damaging of social capital and mutual regard. That is somewhat ironic as the whole point of coming to the host country was to take advantage of its social model. Still, limiting people’s movements for the sake of others seems overly restrictive and therefore integration needs to be helped as much as possible to allow greater mobility with less erosion of successful social models. The diagram at the top makes it clear that an equilibrium of a migrant population in a host country can be reached by either lowering the migration rate or raising the absorption rate through policy enactment. As one of the progressives Collier mentions above, I'd prefer to see that equilibrium reached by raising the absorption rate instead of restricting the migration rate, but a choice has to be made in either case if we do truly value the social models that have been created within high-income countries.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed