|

The last two articles on being happy or being good and the communication market explaining why we speak honestly, lie, or not at all has led to a couple different conversations on the difference between acceptance and tolerance. If you’ve read much of my writing, you have probably noticed a thread that circles around acceptance being highly important, but I haven’t said as much on tolerance.

Acceptance We should be unconditionally accepting of other people. It strengthens social connections and affirms others as thinking, feeling humans who are embodied and live within sociocultural contexts. It also makes forgiveness possible and dissipates anger for one and the same reason - it necessitates seeing people as valid products of their environments who couldn’t act in any other way. Acceptance is really about doing away with the illusion of free will and that people are acting with the intention of harm toward others. It recognizes that, like us, they are doing everything they can to be happy and live with a sense of well-being, satisfaction, and as little pain and suffering as possible. Tolerance On the other hand, tolerance is much less a belief about others as it is our actions toward them. If we allow the existence of a behavior or endure it with forbearance, we are acting tolerantly. It is not necessary to also be accepting of another person in order to be tolerant. As individuals, we can be both tolerant and accepting, tolerant but not accepting, neither tolerant nor accepting, or accepting but not tolerant. Our acceptance depends on our inner beliefs about others and our tolerance depends on our actions regarding them. Some examples can make this easier to understand. If I think that religion is divisive and always harmful, I may view it as an unacceptable belief to hold, but still tolerate others who practice some variety of religion. In the same vein, I could be very hateful and disdainful towards LGBT community members, but still tolerate their participation in society without actually accepting them as people of worth and value. This tolerance may even be socially enforced due to laws with consequences that keep my hatred from turning into violence. On the other hand, I could be hateful and intolerant. For instance, I might be hateful of people with disabilities and see them as “less than” and also not wish to tolerate them in my presence by excluding them from my clubs, workplace, or leisure spaces. The opposite case, in which I am both tolerant and accepting, is easy to imagine. I could see the worth, value, and validity of people that are different from me (i.e. be accepting) and also demonstrate tolerance of their differences of thought and action without imposing restrictions or oppression. Tolerable and Intolerable Harm The last category, acceptance without tolerance, is the most tricky for people to understand. This is the state of being that seems to go against many of our initial predispositions and habits of thinking, but marks a significant level of mature coping and understanding of the world we live in. There are people in our world who need to be separated from the rest of society. These include a huge variety of people, not limited to murderers, rapists, terrorists, and psychopaths that display little empathy for others and take actions to only benefit themselves, such as many of the bankers involved in the destruction of both the housing market and thousands of pensions during the 2008 economic crisis. This is harm that cannot be tolerated by a society that hopes to be cohesive, inclusive, and stable in the long-run. The above examples demonstrate harm that should not be tolerated. That does not mean we can’t accept the people who commit harmful acts as humans with understandable motives; we can explain their behaviors as attempts to be happy while simply suffering from ignorance, insanity, confusion, or some kind of biochemical neurological disorder. They may have acted harmfully, but that doesn’t make them innately bad or inhuman. Even truly sadistic, psychopathic individuals are often suffering from some genetic, developmental, cognitive, or environmental issue that left them with limited or no ability for rational thought. They are not choosing to commit crimes or harm others. I recognize that understanding this may be difficult for people with conservative, individualistic, and religious beliefs, but we do not make our own choices. We do not have free will and we are the product of a system, not lone actors. Three Categories of Intolerable Harm Since I’ve written so much on unintentional actions causing harm and that life is essentially suffering, it begs the question: Which harm should we tolerate and which harm should we not? I think it’s simpler to consider harm we shouldn’t tolerate because that is the much shorter list of categories. Physical harm. We should not tolerate any physical harm to another that is intentional and foreseeable. This includes actions such as murder, rape, torture, domestic violence, road rage, bar fights, etc. It does not include instances in which we have no choice but to harm someone to prevent them from harming others. This happens all the time in war and police work. Obviously, a ban on all physical harm, even for military and police, would have left the world at the mercy of Hitler’s Third Reich and other despots throughout history. Intentional acts of malice. This goes beyond physical harm and includes actions aimed at emotionally, reputationally, or financially wounding others in ways that are foreseeable and avoidable. Examples include school bullying wherein the perpetrator never actually harms the victim physically, but does shame or embarrass them for no reason other than the schadenfreude derived from the activity. Typically, gossip and spreading rumors would take place in cases like this. This would also include acts of revenge over previously real or perceived injury. Active participation in oppressive behavior, institutions, and systems. This is the most abstract and possibly the most difficult to avoid. Systems such as capitalism, nation-state governments, and the like could be argued quite fairly as being oppressive, but are extremely difficult to extricate ourselves from. However, other systems are more easily avoided, such as human trafficking and prostitution. These systems exploit and profit from human oppression and we should not be actively participating in them. Why Deciding What Is Tolerable and Intolerable Harm Is So Hard The aim is to be unconditionally accepting of all people. There is no reason to see others as objects that can be dismissed as less than the humans they are, deserving of both respect and dignity. This does not mean that we must tolerate everyone’s actions and beliefs, which form the premise from which our actions take shape. If someone is not foreseeably and intentionally causing physical harm, acting maliciously, or participating in systems or institutions of oppression, then we should largely leave them alone to do as they please. This is living in a state of both acceptance and tolerance, even if some differences in choice do upset our feelings or clash with our beliefs. This conclusion also makes it much easier to see why issues like free trade of capital goods and climate change are so difficult to manage ethically. Typically, consumers in developed countries like America are not actively choosing to harm people in any of the three ways described above. Of course, American consumerism does in fact cause physical harm to people, business owners do take advantage of workers, and the entire system is oppressive in nature to many of the actors involved. This unintentional harm from consumerism is also the leading cause of climate change, which has the potential to kill millions of people in the coming decades and result in what Naomi Klein has described as a “genocide through apathy”. It’s not that we want present and future people to die as a result of climate change, it’s just that we aren’t willing to change our current lifestyle to prevent them from doing so. But what is the alternative? Consciously deciding about every purchase we make? Even that gets us only so far when our governments, largely beyond our individual control, enter into trade agreements with foreign countries involved in extracting oil from the ground at gunpoint. Deciding not to buy oil or goods is simply a sacrifice beyond what most of us are willing or able to make. I don’t necessarily see this as meaning we are evil people. We should attempt to avoid the intentional physical harm, acts of malice, and active participation in behaviors, institutions, or systems of oppression elucidated above. Being able to do even that much on an individual, person-to-person basis is a great accomplishment. We can’t expect all of our happiness to be overturned tomorrow in order to help others all around the world. It is yet another aspect of life we will have to accept while doing what we can to change it. Rather than be overwhelmed, do your best to “be good and enjoy”.

2 Comments

This is an idea I’ve been toying around with for about a year now. The more I explain it to other people and the more I reflect on it in everyday life, the more I’m convinced it is the best model for communication between two people or parties that I am aware of. Perhaps it has already been studied in economics or psychology somewhere, but I have not seen it anywhere and it is something that is empirically testable, which makes it even cooler.

A Market of Goods In economics, a market is any place, real or imagined, that brings producers and consumers together to exchange goods or services. We have markets for things like meat, which is a good, and markets for things like accounting, which is a service. In any given market, you can typically find a variety of goods or services that compete with one another or complement one another. Goods that complement each other in a market are labeled complementary goods. You can imagine goods like peanut butter and jelly that are typically bought together. When the demand for one of them, say peanut butter, goes up, the demand for the other, jelly, also goes up. The same is true for things like shoes and shoelaces. As people buy more shoes, they also buy more shoelaces. Goods that compete with one another are called substitute goods. These are goods wherein the demand goes up because the price of a competitive good goes up. You can think of very similar goods like Coca Cola and Pepsi. Sure, you probably have your preference, but if the price of your favorite, say Coca Cola, goes up too much, you will substitute it with Pepsi. Hence they are called substitute goods. Other examples might be things like bacon and sausage or cake and pie. Of course, services can work as either complementary or substitute goods as well, they don’t have to be material items like I’ve been using for these examples. The Communication Market What the short introduction above allows us to do is imagine human communication as a market with producers and consumers. One person is producing communication and one person is consuming it, the speaker and listener respectively. Obviously, humans communicating aren’t producing material goods, but rather language. Once you understand that communication between two people is a market, it is easier to see the types of “goods” possible in the market. We can choose to speak or not. If we choose to speak, we can speak honestly or lie. That leaves us with three alternative “goods” to choose from and they happen to work just like the substitute goods described above. Everyone will have their preference for communication, just like everyone has their preference for Coca Cola or Pepsi. Some people might prefer to speak honestly as their favorite form of communication. Some might prefer to lie, say a pathological liar, who lies for no reason. And some might prefer not to speak at all unless necessary, perhaps someone who is both extremely shy and introverted. The exciting part of this communication framework or model is the recognition that substituting one of these communication goods for another happens for the same reason that someone switches to Pepsi whose first choice is Coca Cola, the price on their preference becomes too high. Taxing and Subsidizing Communication Everything above gets us to this point. If we want someone to speak honestly who isn’t or tends not to, we need to subsidize that mode of communication or tax the other two forms of communication. This simply means encouraging speaking honestly and making it costly to the individual to lie or not speak. If we pay attention to communication, we see this all the time. Our society generally sets up communication so that lying is extremely costly to most people in serious matters. Examples like plagiarizing in school, committing perjury in court, or defrauding customers or the IRS all have serious consequences. These situations also tend to make not speaking very expensive as well, which leaves most people in the situation of speaking honestly because it is dramatically cheaper than the other two alternatives. However, even more interesting than the situations in which we tax communication in order to ensure a higher rate of honest speaking are the situations in which we give lip service to wanting honesty, but turn around and tax it when it is produced. This is the exact opposite tactic we would expect if people were genuine about their desire (demand) to consume honesty as their preferred good in the communication market. We see this most often between close friends and family and promoted in most cultural norms of social connection. Examples of this second situation are friends that tell us we can share anything with them, but get extremely angry when we disclose some character trait, feeling, or action they disapprove of, perhaps something like not liking one of their other friends or smoking cigarettes. Naturally, these types of feelings and action may not be great in themselves or some of our best qualities, that’s why we might tend to lie about them, but we also can’t be expected to speak honestly about them if we are taxed by the listener with judgement, rejection, or contempt. Deciding What Matters It’s been my experience since viewing communication in this format that most people don’t actually want honesty between close friends and family. If they truly did, they would do everything they could to subsidize that form of communication by showing gratitude and acceptance whenever someone is honest with them. Instead, they lavish heavy taxes in actuality and then become even more self-righteous when they find out someone is lying to them. We can’t have it both ways. If we truly, deeply want honest communication, we have to be prepared to hear whatever honest communication gets produced. We have to be willing to listen openly. We can’t punish, take revenge, or act vindictively. We have to attempt to build stronger relationships and work together through constant dialogue. It’s fine not to like what someone says, that in itself does not count as a tax. Plenty of rational adults can disagree on what is best. Two adults can even agree that the feeling or action being shared in speech is not the best part of what makes the speaker a person. But that absolutely is no reason to treat them as "less than" or make them feel small. Instead, it is an opportunity to look at the person can grow and develop in their process of becoming a more fully actualized, fulfilled, and congruent human. So this is what it comes down to, speaking honestly, lying, or not speaking at all is not just a product of the speaker’s character. It’s also a result of the interaction with the listener. A listener needs to decide what matters most to them in any relationship they have with another person and do their best to convey that as authentically as possible. The more demand you show for honesty as a listener, the more honest communication the speaker will produce. I’ve been writing a lot recently on responsible action, suffering, depression, emotions and greatness, deciding who loses, children, competition, political-economy, and well-being, but not much directly on “goodness”.

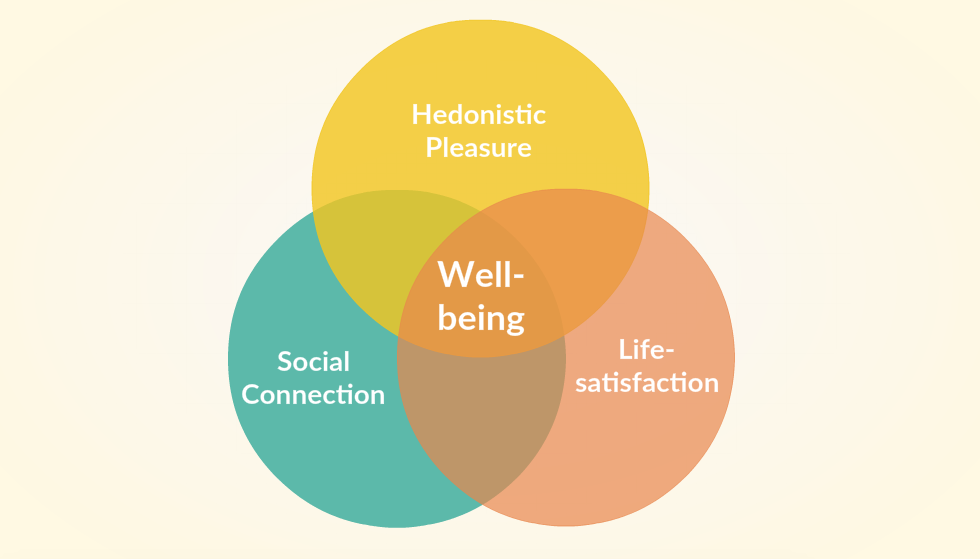

However, I’ve recently had a bit of what I would consider an insight on the sticky and intractable nature of goodness that I think is worth sharing, discussing, and analyzing a bit more. Being good is inherently a social quality. Goodness depends on relation to others for it to make any kind of sense at all. A person is not “good” in a vacuum, but only in how they interact, treat, and respond to those around them. Happiness, or well-being, certainly involves others, but is not solely comprised of our relations with them. It has other aspects. See my algorithm for well-being to see how hedonistic pleasure, life-satisfaction, and social connection are all major components of well-being. Recognizing how goodness and happiness are fundamentally different - innately social versus innately individual respectively - lets us see how they often (always?) work as trade-offs. Defining Goodness Being good can be defined rather simply: don’t harm others and help them when you can. Putting this into practice is the tough part. The tricky parts are the two verbs, harm and help. What classifies an action as harming or helping? People have struggled to answer that for centuries. Consequentialists believe that the consequences of an action make it good or not. Non-consequentialists typically believe that intent matters most in deciding the answer. Utilitarianism of the Bentham, Mill, and Singer variety best exemplify consequentialist approaches, whereas duty ethics of the Kant variety are the foremost non-consequentialist approach. Intent seems to matter more for self-evaluations of whether we believe ourselves to be good. We often will still see ourselves as good if we intended the best possible outcome given what we could foresee. However, we are often judged on the consequences of our actions and very often are not able to plead ignorance as our defense when others are involved in evaluating our goodness. This is particularly true in law, but also of our acquaintances, friends, and family. How Your Happiness Harms Others Putting aside some of the philosophical difficulties outlined above in deciding how to decide what is good, let’s look at some examples. I’ll use examples from the three components of well-being listed above. Hedonistic pleasure. I most typically think of things like sex, drugs, and food in this category. Does having sex with a partner other than your own count as harm? Society says so. Clearly there is no physical harm, unless we bring some sort of STD home to the unsuspecting. So that means the harm is psychological in nature. Often it is hurt feelings attached to ego, shame, or jealousy. Hurt feelings are typically not considered good reasons for not doing things outside of relationships. You rarely see anyone saying not to buy an expensive watch or nice car because it will hurt the feelings of someone else. Then there is the single female who sleeps with many partners and is considered a “slut”. A bad woman. Less than pure. Probably not respecting of herself. Often she and her family with have to live with shame and potentially be the victims of outright mean and hurtful comments or actions from others. So even sex between two consenting, single adults is often troublesome. This is another societal belief, but does seem to be slowly changing. However, we do still see examples of news stories where girls are shamed for being involved in the legal business of pornography, even while attending Duke University. How about drugs and food? These may cause harm to others as well. Drugs can lead to direct physical harm of others, but also the emotional pain of family and friends who believe you are being self-destructive. Again, this is really dependent on the social norm attached to the drug. Alcohol is very tolerated in most of society, even though it is much more harmful than many illegal substances. Food? Yes, absolutely. Obesity costs America over $200 billion annually. That definitely harms the economy, productivity, and relationships of all kinds. An example unrelated to obesity is the jealousy, anger, resentment, and hatred that can be aroused by those who cannot afford to dine at expensive establishments like Ruth’s Chris or other high-end steak houses. This latter type of harm is much closer to the infidelity described above. On top of the emotional harm that is possible, we can consider the opportunity cost and environmental destruction the food we purchase incurs. Ideally, we would eat vegetables grown in our backyards that don’t require long-distance shipping or destruction of rainforests. Naturally, these aren’t the only ways to engage in hedonistic pleasure. The use of electronics, cars, and air conditioning can all be pleasureable experiences. They are also directly connected to oil and mineral use that often employ highly extractive and destructive means in regards to both the environment and human lives. Life-satisfaction. This is connected to meaning, purpose, goal accomplishment, and congruence. Many of these will overlap with the basic pleasures mentioned above. It is difficult to accomplish major goals without utilizing resources, many of which are attached to corrosive trade practices. One of the few ways in which life-satisfaction would not lead to harm is by becoming some sort of ascetic monk that lives alone and sustainably in the mountains. The downside with this lifestyle choice is that it effectively makes one subject to chance illnesses and injuries. It is pretty difficult experience a sense of well-being when suffering from a preventable disease or broken limb. You may not be harming others through consumption of material goods or interactions that lead to their psychological suffering, but you may very well be causing harm to yourself. This also would assume that no one would be suffering because you chose to leave their life. Most of us have loved ones that would find it akin to sudden death if we picked up and left from their lives for the sake of eliminating harm. They might even be inclined to label us as selfish for voluntarily walking out of their lives permanently, instead of being taken away by some unforeseen, unchosen tragedy like a car accident. Social connection. This aspect may seem the least likely to cause harm, but easily does so in many situations. This often stems from the difficulty we looked at above between defining good on the basis of intent or consequence. Others almost always judge us on the consequences of our actions, not our intent. Generally speaking, this leads to them becoming angry, hurt, or experiencing some other form of destructive emotion. It is a rare day that someone doesn’t misunderstand a joke not intended to be mean-spirited, or interpret not picking up coffee for them when you out as thoughtlessness or forgetfulness due to a lack of care and concern. These misunderstandings between people based on outward results is the general bane of social interaction. These are rather small examples, but they escalate quickly when we connect them to larger social issues like abortion. Is terminating a fetus causing harm? To whom? Does this interfere with the well-being of the would-be mother because she has to postpone or walk away from her goals and break with what makes her feel like a congruent person? Does it preemptively cut off all well-being whatsoever for the future person that no longer exists? Clearly, not harming others is a very difficult business. The best we can do is decide when it is acceptable to harm others, in what ways, and to what extent and then try to make good on those agreements. Deciding Who Loses: Part Two In the article linked directly above on deciding who loses in mutually exclusive circumstances, I introduced a simple tool that could help find the solution with minimal social grief. The two parties could each determine how much suffering or well-being the choice would make for them, and in comparing the two subjective realities, select the “lesser of two evils”. This, of course, was after first trying to find situations that were win/win. There is no need to resort to someone losing when it comes to deciding what to do if both can win. What I failed to do in the initial article was make the connection between figuring out how to maximize well-being for the two parties involved compared to maximizing the good. After all, selecting maximal well-being is simply one goal worth pursuing. The tool introduced in the original article is simply not needed if merely one of two parties is focused on the goal of maximizing their goodness. If they are focused on maximizing their character trait of “goodness”, then they can simply submit to whatever choice the other party wants instead of trying to decide what is subjectively the least worst option. In this case, being a good person simply means volunteering to let the other party have their way. Although, even here, we need to make sure that letting the other have their way doesn’t involve them intentionally hurting others. In that case, being good means preventing those actions. Good vs. Happy What should be clear by this point is that deciding to maximize well-being is a goal. We select our goals. We decide to put happiness above other options. In an era where research on happiness and the field of positive psychology are flourishing, this seems natural. This hasn’t always been the case, however, and we could easily select maximizing being good as our goal. This is essentially what the “effective altruist” movement is doing. A slew of books have popped up recently detailing how to do The Most Good You Can Do by Doing Good Better, protecting The Life You Can Save, or by saving Strangers Drowning. All of these books are not about individuals getting the most happiness out of life, but rather helping the most people and doing the most good. In doing this though, there is an inevitable trade-off with happiness. Joshua Green, author of Moral Tribes, has termed this disposition for sacrificing your own happiness for the sake of others as turning yourself into a “happiness pump”. What he is hinting at is that in the extreme, we can always donate our time, energy, attention, and money to causes that would make others better off up to the point where we have literally none of those resources for ourselves. In fact, that is close to what Peter Singer has argued for - donate all of your money to those in need up to the point at which donating more to someone suffering would cause you to ultimately suffer more than they are. By taking this stance, you have become a “happiness pump”. Taking whatever potential happiness you could have and turning around and pumping it into others who are less fortunate. Greene argues that this hardly seems like a worthwhile way to live. That’s true if well-being is our goal, but not if goodness is. Maximizing the good really does require becoming a happiness pump. Social Democracy as a Model In seeing this tension, I find it useful to turn to the political arena where the tension between liberty and equality was seen long ago. Political scientists have recognized that unconstrained liberty leads to high levels of inequality and the strife that accompanies that state. Conversely, perfect equality does require sacrificing individual liberties to ensure that everyone has the same political and economic outcome. As Jonathan Haidt’s research has shown, this is just a difference in values. People who value caring and fairness are more prone to value equality. People who value liberty most will generally be in favor of tolerating more inequality. Rather than settle on unregulated capitalism or unadulterated communism, which give maximal liberty and equality respectively, many countries are beginning to sort out a stable middle ground with social democracy. This seems to be exactly what ethics needs in the tension it finds between happiness and goodness. This is not too hard to do in theory, but has been difficult in practice, largely to my mind because people simply aren’t seeing this trade-off as a trade-off. People believe that we can be maximally happy and maximally good. This simply isn’t the case. It’s like wanting to have maximal liberty and maximal equality at the same time. Examples of this abound everywhere. Bill Clinton, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Tiger Woods are all celebrities that would be largely considered “good” people if it weren’t for their marital transgression that, at the heart of it, involved them chasing a form happiness within the realms of hedonistic pleasure and perhaps connection. Rather than condemn them, we can recognize their decisions for what they were, choosing happiness over goodness in specific circumstances unrelated to their other decisions where they did favor goodness over happiness. Even the most generous philanthropist in history, Bill Gates, owns a $123 million home in Washington, something clearly aimed at happiness over goodness. Should we fault him for this choice or condemn him as bad for not adding that sum to his foundation? The Cheat Meal Effect Thinking about these necessary and innate trade-offs that must be made between between the two states of being happy or being good, I’ve come to think of them in a similar manner to “cheat meals” when dieting. In this context, cheating is relative to whatever you are dealing with when thinking about your own happiness or goodness. It can be splurging on a luxury travel destination with good accommodations to improve your happiness versus donating the same amount to Against Malaria Foundation to increase your goodness. The main point is to recognize the goals and values you have first. Second, you figure out how to maximize your energies long-term to reach those goals by allowing yourself to discard the illusion of being both 100% happy and good at the same time by giving yourself an occasional “out” so you don’t go crazy. What’s nice about this strategy is that it is more sustainable. It lets you “stick to your diet” the majority of the time and not feel bad when you decide to cheat every once in awhile. As any dedicated dieter will tell you, having the mental break from perfection can make compliance much easier. If you know that you get to indulge on Friday night by eating all the donuts and cupcakes you want, it is much easier to be strict and on your diet the rest of the week. People use this tactic with diet and exercise already. Dan Savage and others are arguing that it should be more normal with committed, monogamous relationships as well. Similarly, I’ve already mentioned the case of spending time, energy, attention, and money on self versus others. We can commit to a diet or exercise regimen 95% of the time and still get good results if we cheat 5% of the time. We can commit to a 50-year relationship or marriage with another person and still have other loves along the way. We can commit to donating 10-50% of our income to the most effective charities and foundations and still buy ourselves luxury items with the leftover. None of these things must necessitate self-appraisal as a bad person. It just means that we’ve recognized the conflict between happiness and goodness and made decisions about where to draw the line. Conclusion I can imagine a future where physical needs for food, water, shelter, and clothing are taken care of for nearly everyone on the planet. It is possible that we become wealthy enough as a species that we don’t have to worry about the trade-off between consuming for our own happiness and donating to charities for the benefit of the destitute. Even with that material “utopia” as it were, people would still need to figure out how to cope with the psychological harms we cause to each other in our relationships. That requires more than physical capital accumulation and (re)distribution. It requires recognizing that the individual pursuit of happiness often causes harm in unintended ways. That psychological hurt is best coped with by searching for understanding and acceptance, not by assigning blame, guilt, or labels of others as bad, evil, or twisted. That requires an evolution of the spirit within every individual on the planet. To recognize as Alain de Botton put it that, “My view of human nature is that all of us are just holding it together in various ways — and that’s okay, and we just need to go easy with one another, knowing that we’re all these incredibly fragile beings.” I realize I discuss well-being a lot in my writing, and it is one of my central interests, so it’s probably best that I explain where my ideas on the topic come from. Because it is a huge topic and one that I’ve spent so much time thinking and reading about, there is no way that I will be able to cover and include everything here. I am only attempting to capture a bit of the history of my thought on the matter and where I currently stand. With that in mind, let’s get started. Personal History I first read about the topic in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics in high school in which he settles on eudaimonia as “the good life”. This more or less entails reflective contemplation and the development of virtues, characteristics such as moderation and temperance in all things. This also known as “the golden mean”. This work and much of his other writings (see Politics) have been classified as what modern ethicists describe as “virtue ethics”. It is a system, as the name implies, that believes in developing virtues as the path to well-being. I then picked up an anthology of western philosophy, which I unfortunately cannot remember the title of, but was very similar in nature and scope to this textbook, Classics of Western Philosophy. It traced the development of ideas and philosophic concepts from the ancient Greeks up to 20th century thinkers. This was the first place that I read about Epicurus, Aurelius, Descartes, Spinoza, Hume, Kant, Schopenhauer, Mill, Nietzsche, James, and Russell. Nietzsche was the one that stood out and I began reading the majority of his works, along with the major works of Epicurus, Aurelius, Seneca, Cicero, Spinoza, Schopenhauer, Mill, many of Russell’s, Lakoff, and Noddings. In addition to the primarily philosophical texts above, I read a number of Western and Eastern works that were primarily religious in nature. Those included Tao Te Ching, The Bhagavad Gita, The Kingdom of God Is Within You, The Analects, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, The Reason for God, The Imitation of Christ, The Joy of Living, and Islam and the Future of Tolerance. These exposed me to the deontological ethical systems, or “duty ethics”, from Kant and utilitarianism from Bentham and Mill. Nietzsche argued that modern man would have to “overcome” his previous ethical systems in a complete “revaluation of values”, something I still largely agree with. Lakoff’s text above does a fantastic job of comparing philosophies throughout time and grounding ethics within an embodied system without resorting to anything metaphysical. In college, I also stumbled upon the book Destructive Emotions, which is a dialogue between cognitive scientist Daniel Goleman, author of Emotional Intelligence, a gift my aunt gave me while still in high school, and the Dalai Lama, spiritual leader and former head of state of Tibet. Both of these books predisposed me to reading The Art of Happiness, yet another work coauthored by the Dalai Lama and a western doctor, this time a psychiatrist instead of cognitive psychologist. The Art of Happiness became a turning point because it was able to shift my mindset from that of complete relativism, to providing a foundation for morality in happiness. The basic premise is that we all seek happiness and wish to avoid suffering. By describing both the psychological phenomena examined in Buddhism and the brain science examined within neuroscience and psychiatry, the book made a huge impression on me. It persuaded through both subjective and objective evidence, something I often aim for in my own teaching and writing. From here, I dove into the ever growing research in positive psychology. I began primarily with the wonderful textbook A Primer in Positive Psychology. I then quickly moved onto more specific aspects of positive psychology like flow, exercise and the brain, aging well, making decisions, stress, relaxation, motivation, rewards and incentives, mindset, creativity, meaning, mastery and expertise, humanism, optimism, self-actualization, the effects of our subconscious and free will, attention and energy management, intelligence, thinking, self-renewal, emotion, marriage, and learning. All of this happened over a two year period while I was also completing a master’s degree in education focused primarily on how we learn, largely by investigating both language, literacy, and culture. Upon completing the degree, I moved to Dubai and then Singapore where my next bout of reading began. A friend in Dubai introduced me to the work of Sam Harris whose book The Moral Landscape had a huge impact. It discussed, similarly to the Dalai Lama and Goleman, that morality’s foundation should be the study of well-being and suffering, and that it is possible to treat that study scientifically in much the same way we study physical health. Seeing as I was already familiar with positive psychology treating happiness in this way, the study of morality in this manner made perfect sense. After the move to Singapore, I stumbled onto the work of Peter Singer and his book The Life You Can Save. This, too, was responsible for a large shift my thinking. I had already studied the works of Aristotle and the Greeks who discussed philanthropy, or the love and service of humanity, at length. I had also been exposed to the idea from Buddhism of the boddhisatva, an enlightened buddha who chooses not to go to nirvana, but instead stays in our reality to help others reach enlightenment. So too with Maslow and his later work on self-transcendence who “proposed that people who have reached self-actualization will sometimes experience a state he referred to as ‘transcendence,’ or ‘peak experience,’ in which they become aware of not only their own fullest potential, but the fullest potential of human beings at large”. Even with all of this exposure to helping others, on top of positive psychology’s largest single finding “that others matter” for our happiness, I never felt a sense of agency in being able to affect change among those suffering and only sought to affect my own happiness. I largely blame my undergraduate degree in economics for this outlook because of its focus on development work being rather unpredictable and often causing more harm than not. Sure, we could try to help, but we have 50/50 odds of just making it worse. Better to focus on the self. Peter Singer’s work has convinced me otherwise. Millions of people die from preventable diseases and poverty every year. To not attempt to help is morally culpable. Obviously, without accepting the evidence from positive psychology and Harris’ The Moral Landscape basing morality on well-being and suffering, this argument falls apart. However, both are grounded in empirical research and as Harris points out, if we can’t agree that certain states of being are worse than others, then we really have no point of agreement for even having a dialogue. Being in a state of depravity is clearly worse than not being in a state of depravity and we should do our best whenever possible to help alleviate that suffering in ourselves and others. What’s more, the majority of the research I’ve pointed to above demonstrates that helping others will make ourselves even happier. As the protagonist from Into the Wild states, “Happiness is only real when shared.” Turns out that all psychology, neuroscience, and economic research says this is true. The Algorithm SWB = f(HP, LS, SC) Subjective well-being is a function of hedonistic pleasure, life-satisfaction, and social connectedness. OWB = f(H, W, E, S) Objective well-being is a function of health, wealth, education, and security. Quality of life is a function of subjective well-being and objective well-being.

Subjective Well-being The subjective well-being function is what I want to focus on. The objective well-being function is certainly important, but I feel more intuitive. People are often able to look at a person’s life and tell you whether they are objectively well off. This is often a product of the political and economic situation in which the person lives, but also socio-cultural circumstances. I personally have found the capabilities approach to economics and human rights the most useful to draw on with regard to objective well-being. Indices like the UN’s Human Development Index and the newly created Social Progress Index do a decent job of capturing much of these objective qualities, with the obvious caveat that they could also improve or become more comprehensive. So while national, international, and supranational organizations have already done a decent job in measuring objective well-being, therefore making it redundant to cover here, there has been less consolidation of the findings within the area of subjective well-being among the various social sciences and humanities. In the function for subjective well-being above, I’ve included three central dimensions. These come almost verbatim from The Psychology of Desire, which states, “Finally, all might agree that happiness springs not from any single component but from the interplay of higher pleasures, positive appraisals of life meaning, and social connectedness, all combined and merged by interaction between the brain’s networks of pleasure and meaningfulness” (p. 129). The chapter containing the above quote looks at and examines hedonia specifically and is what is referred to by “higher pleasures”, which the authors contrast with Aristotle’s eudaimonia or “cognitive appraisals of meaning and life satisfaction” (p. 129). Finally, they add social connectedness based on research within the rest of the text. These aspects of subjective well-being fit within a much wider context of research on the topic. I feel they are capable of encapsulating the majority (all) of the other findings with the nascent field. Below I will explain just how this is so. Hedonistic Pleasure The first dimension is hedonism, which is concerned with life’s pleasures and pains. This goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, where it was most carefully reflected on by Epicurus in his major work referenced above. For Epicurus, hedonism was largely concerned with eliminating the pain in life and not nearly as self-indulgent as modern day “epicureans” would have us believe with their concern for food and drink. Thankfully, we don’t have to go back that far as modern positive psychologists have found that positive emotions do in fact make us happier (no duh!). Even our dreaded materialism can, in fact, make us happier if we spend on and consume items which are congruent with our personalities or allow us to enhance our experiences, especially if they increase our relatedness to others discussed below. This aspect of well-being also includes the finding that novelty in our experiences and pleasures does make us happier. Beyond mere material and experiential consumption as sources of pleasure, this dimension would also include pleasurable states of being, such as good health, physical and psychological security, engagement in flow, and the ability to exercise autonomy, all of which have wide support within research as contributors to well-being. Life-satisfaction The second dimension is about taking a step back from the present feelings of happiness that you may experience day to day in order to get a wider perspective on life. Broadly speaking, does your life having meaning, purpose, and a sense of accomplishment congruent with your values? Do you have a sense of competence or even mastery? The category is largely about self-selected goal attainment, in contrast with the previous dimension’s focus on desire satiation (a subset of goal attainment). In exploring this variable, it’s best to begin with competence, which has one of the most robust findings as a basic human need among any of the items discussed here. Competence, along with autonomy and relatedness, can be found among many of the most prominent studies on what motivates human behavior. As we grow in competence, we often seek ever greater challenges through self-regulation based on our values, purpose, and meaning in life. By self-regulating, we are able to experience a sense of congruence regarding our personal beliefs and the goals we seek. This sense of congruence and actual achievement of our selected goals provide a deep sense of accomplishment. By iterating this process enough times, often with the help of deliberate practice and deep work, we are able to approach mastery, a deeply rewarding experience that often fills us with great pride. Social Connectedness Last, but most importantly, is our deepest human need to experience social connectedness. This is almost certainly the most important thread tracing through all of the research on subjective well-being. Connection to other humans is what allows us to most fully develop and grow as individuals and groups. In fact, modern neuroscience is beginning to show that morality is built on the foundations in our brain most closely connected to cooperation. Cooperation is the mode of goal attainment, in contrast to competition or independent striving, that most closely contributes to both of the previous dimensions above. By cooperating, we are able to satisfy our desires better and develop greater empathy for others, the basis of human connection and forming a strong concern for others (i.e. altruism). In learning to see others as subjects and not just objects to be overcome, we allow them to be more vulnerable and are able to accept their flaws, mistakes, and shortcomings, a process that many psychologists have found integral for human growth. Putting It All Together As I mentioned above, I will not be going into the components of objective well-being as they are more straightforward, have greater agreement, and therefore would be redundant. However, in looking at the algorithm above, what is important to realize is that it is the combination of both subjective and objective well-being that make up overall quality of life. Living standards can be objectively high and a person will still not experience a high quality of life if they are experiencing depression or other forms of subjectively low well-being. This is most evident in the alarmingly high number of suicide deaths in the developed world (America has suicide as the tenth highest cause of death in the country). Worldwide, a person is more likely to die from suicide than homicide or war combined. The most difficult aspect of this algorithm is finding the appropriate balance among the three components of subjective well-being. Oftentimes, our hedonism can stand in the way of our life-satisfaction and connection to others. Two short examples among an infinite number are when our short term desire satisfaction for sweets stands in the way of our chosen goal of being healthier, or when our hedonistic addiction to the pleasure of drugs destroys our connection to friends and family. This same issue exists for the other two dimensions as well. For instance, an obsessive focus on life-satisfaction within the narrow sense of goal attainment can lead us to avoid hedonistic pleasures and social connection through compulsive work, while an obsessive or dependent state of social connection can also detract from our enjoyment of self-centered pleasures and overall life-satisfaction by narrowing what it means to be fully happy and competent. What this boils down to is developing an ever larger sense of compassion and understanding for each other, which can allow us to accept people when they do make tradeoffs in the various dimensions, instead of jumping to judgement, which only creates division and alienation. If we recognize that we are all striving to be happy and fulfilled in life and that pursuit encompasses more than just the emotional feeling of positivity, the person that is aiming to enhance their well-being through a different dimension than you think best won’t be seen as wrong or bad. As long as we aren’t intentionally hurting one another, it should be accepted by all when a person chooses to increase their happiness through any of the three dimensions above. It is nearly impossible to eliminate suffering entirely, but we can alleviate it by cooperating and utilizing an “ethic of care” in our everyday lives. This propensity to enter relationships and address people with care as our first inclination can lead to a more connected and peaceful world, which will lead to a happier and better world. My last article was on why I think “competition is stupid” for modern individuals to uphold as a cherished value that benefits individuals and society. One important reason that competition is received as a self-evident benefit is its connection to American capitalism. In No Contest, Alfie Kohn states that, “Capitalism can be thought of as the heart of competitiveness in American society” (p. 70).

This is a reasonable argument to make regarding how the specific circumstances in America have turned out, but should not be taken as true in general. Capitalism does not necessitate competition. Competition is zero-sum by definition. When you win, I can’t. Capitalism is not. Ergo, there is no innate reason for competition to be the sine qua non of capitalism. So while I agree with Kohn’s overall points in building a case against competition, I don’t view them as a huge strike against capitalism per se. I’d like to reflect in greater detail on:

Warning: This post will be a bit more “classroom lecture-y” than I’m typically like, but you can skip to the conclusion for all the main points if you’d rather not see how I arrived at them. Capitalism I can understand why Kohn would make his above statement. American capitalism and the beliefs we hold as a culture do promote competition. We have been sold a belief that competition is what drives capitalism and that “only the strongest shall survive,” which is partly true. In a market that can only reasonably support one firm, such as natural monopolies like utility services and railroads, often the firm with the cheapest product will capture the entire market and all other firms will go under as a government lends their support to the firm’s efforts to provide some large-scale infrastructure to ensure supply. The above example does fit with Kohn’s definition of competition as attaining a mutually exclusive goal. If two firms want to remain open and dominate the market, but only one can, then they have mutually exclusive goals of being that firm. This reflects the fact that both firms have the same goal - to remain open - more than it reflects an inherent aspect of capitalism. Americans could simply decide to vote that large-scale natural monopolies be run by the government, which would take away the goal of being the firm in that market. Another aspect of American capitalism that promotes competition is inherent to our legal system, which mandates that firms maximize profits for shareholders, thereby dictating the goal by which firms measure themselves. This is again not innate to capitalism, but part of our socially constructed legal system and therefore possible to change. We could legally obligate firms to chase different ends besides maximizing profits, such as maximizing employee and consumer well-being. This is certainly more difficult to quantify and I am not arguing otherwise, only that it is theoretically possible to select different goals. Two examples of projects that look in this direction are the developments of the Human Development Index and Gross National Happiness, which attempt to capture well-being in a more holistic way than simply GDP. Surely if entire countries and the UN can make the effort to measure things such as these, our legal system could figure out a manageable way to set different goals for firms if the desire were there. So if competition is not the central characteristic of capitalism, what is? The central characteristic of capitalism is individual decision-making and choice, as opposed to any sort of centralized decision-making. Free markets allow individuals to make their own choices about what is in their best interests and for firms to respond by producing goods and services to match those desires and needs. This should make a connection to well-being quite obvious. It is much easier for me to decide what will contribute most greatly to my own well-being than for some central authority to do so. Capitalism allows this to happen rather efficiently through the use of markets. Marxism Karl Marx originally wrote about his economic theory of communism as an endpoint in a trajectory he saw playing out through his analysis of history. It was much more an observation of history, with a prediction for the future, than a prescription. He observed that humanity initially lived at the subsistence level in a state of equality during the hunter-gatherer era. Everyone was equal because essentially everyone was poor. They had equality through poverty. This changed over time as technology improved, but led to feudalism where powerful aristocracies could control the labor tied to the land it worked on. With the continual evolution of technology, this situation eventually shifted to capitalism as merchants became rich and uncontrollable by the aristocracies. Seeing this pattern of shifting political-economic landscapes, Marx predicted that eventually the laborers (proletariat) in a capitalist society would grow tired of having a lower quality of life than the owners of capital, who would become a smaller and smaller percentage of the population with more and more of the total wealth. This inequality would lead to an overthrowing of the oppressive capitalists by the laborers and result in the formerly oppressed laborers being the oppressors. Marx, however, did not see this “dictatorship of the proletariat” lasting very long and predicted that eventually the new oppressors would do away with institutions because all would decide to live in a state of equality where laws and police weren’t needed. What’s most important to realize about this economic theory is that it is still largely individualistic. The laborers simply “gain class consciousness” of the unequal situation and realize that they are not benefitting from the capitalist system as much as they could be due to the owners of capital capturing the majority of the wealth. This is almost exactly what happened in the Occupy Movement that chanted, “We are the 99%”. Individuals in Marxist communism are deciding what best maximizes their well-being. The political will of the majority of the population chooses to live in a state of equality, rather than a state of inequality that benefits only a small percentage of elite capital owners. It is a turn away from competition and inequality toward cooperation and equality by choice. This is not how communism as turned out in practice. Communism in Practice While capitalism and its organic evolution into Marxist communism focus on individuals making decisions by cooperative and collective means, communism as it has been historically implemented focuses on collective “equality” through centralized decision-making. In practice, this has consisted of an authoritarian government doing the decision-making, but as will be discussed in the Democracy section does not have to be the case. In order to reach a state of equality in practice, people like Vladimir Lenin believed it was necessary to create a “vanguard of the proletariat” to push the working class into moving towards and adopting communism. This allowed the “vanguard” to simply become a new set of elites and begin making decisions. Once in power, these vanguards operated as both political and economic decision makers with little accountability from a democratic voting public. That turns out to be the main problem of communism in practice. Trying to decide what is best for individual well-being that is not your own is very difficult, especially if you are responsible for the individual well-being of millions of individuals in a large nation-state as a central planner. There is simply no way that a central decision-maker can go about that task in an optimal way. They would literally need to know millions of pieces of information in order to figure out how to distribute and utilize a nation’s resources. Who should get what goods and services? How much should they get? Do any innovations or discoveries need to made in order to produce the goods and services needed? How many researchers are needed? The list of questions that need answers in a large economy are way beyond any central planner once you begin asking them. With all this in mind, it is easier to recognize that centralized planning in communism is a historical byproduct of authoritarian governments more so than Marx originally intending it. Democracy All of this brings us to democracy, which is the political theory that favors individuals making decisions instead of an authoritarian figure deciding for them. Rather than trust absolute power to a single person or small group, it is better to decentralize it to as many people as possible. A voting public is able to hold elected officials accountable for their actions with the threat and ability to remove said officials if necessary. Democracy is a political system, not an economic one like capitalism and communism are. Therefore, it could hypothetically be decided in a democracy to create a central economic authority that could act in a traditionally communist fashion. This isn’t likely to happen, however, as most nation-states that value individual liberty in politics are also likely to value the same thing in economics. The political will of the people just isn’t likely to turn over autonomy to a central economic planner in a democracy. Instead, it is much more likely that democracy turns to an economic system like the world is seeing in Scandinavian countries. These countries operate as social democracies. These political-economic systems are much more stable and sustainable than the traditionally unequal capitalist societies or historically authoritarian forms of communism. This is because social democracies allow individuals to make political choices through voting just like traditional democracies, but unlike authoritarian regimes, while also allowing individuals to make economic choices through free markets just like traditional capitalist systems. The difference is that the populace has collectively decided to live with high taxes in order to support socially beneficial programs after the market has already been allowed to create wealth, which as you will remember is much more efficient than a central planner attempting to do so. The population has chosen the taxation and redistribution, not been forced into it. Conclusion So there you have it. Capitalism does not require competition. Capitalism is about individual economic choice and decision-making. Marxist communism can be viewed as an organic evolution of capitalism towards more equality through the collective will of the individuals within society. Communism in practice has been much more about authoritarian and centralized political and economic decision-making, which is its main problem. Capitalism and democracy both allow maximal individual autonomy over economic and political decisions respectively, which is why they work so well together and allow society to move towards systems such as social democracy found in Scandanavia where people choose to cooperate for the benefit of all members of society. I’m beginning to ask myself more and more frequently, “What use is competition? Does it really serve any good purpose?” I’ve been going about this question two ways: asking myself and reflecting on it in a subjective manner tied to all of the experience and knowledge I have gained and also by reading on the topic and looking, searching, and questioning whatever I read. So far, nothing. I cannot currently see a legitimate use. In fact, I think the biggest revolution in history may come when humans decide collectively that it isn’t a good at all, but something to be overcome and rejected. Reflections I’ve asked several classes worth of my economics students what would happen if we gave everyone a basic income and no one had to work for a living. They all initially said that people would have no incentive to work and that nothing would get done. This took me down the path of incentives, which I currently view as possibly the biggest lie in economics and our modern world in general. The belief that people must have incentives to produce anything is simply not true. I can point you to research on motivation. I can explain the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic rewards. I can point to the research on creativity and the connection between rewards and complex tasks. But I find it easier to reflect on the individuals in our world like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg. Jonas Salk, Nikola Tesla, Benjamin Franklin, Leonardo Da Vinci, Aristotle, Friedrich Nietzsche, Claude Shannon, and the list goes on. Or consider revolutionaries, who often suffer through years of violence and discord for a larger purpose that can ultimately bring great satisfaction and meaning to their lives and the lives of others. Scientists, philosophers, computer programmers, writers, and everyone else that produces something new and novel that requires hours, weeks, months, and years of hard work, dedication, teamwork, and toil simply do not do it for the incentives and external rewards. Let’s take one very simple example. Name one person involved in creating the internet. I’ll wait. I’m guessing the majority of people cannot. That’s because it was invented as a research and government project to help with communications. It simply let them get on with their work better. On different note, “Fleming's accidental discovery and isolation of penicillin in September 1928 marked the start of modern antibiotics”. Many important discoveries and inventions have happened in exactly these ways: to make our already meaningful work easier or as happy accidents. Creation and production, especially of complex, world changing ideas, is most often its own reward or done for altruistic purposes (see the revolutionary reference above). Many of the people who have invented scientific breakthroughs have not been the ones to make billions on the ideas. Scientists often toil in somewhat obscurity with the help of basic research grant money and then have to turn over that research and breakthrough to the university they work at, the government that employs them, or a major corporation who can then turn the ideas into profitable products. The creation itself is no product of huge incentives. On a personal note, I cannot remember the last time I did something for money. Granted, I have a very fortunate life and have been lucky never to have been truly hungry or wanting. However, that only goes to help make my point. Given a life where food, health, and education are not the primary aims needing to be met, I have been completely free to pursue challenges, learning, and development for their own sake. I now work essentially only for whatever growth opportunities a job or task presents with the ultimate goal of being able to give more back to society and world through that process. This is no coincidence. “A large number of studies have confirmed that humans across cultures have a need for autonomy, competence, relatedness, security, and self-esteem”. These are basic needs that we will search out as humans without the need for external incentives. It is because my needs for security, autonomy, relatedness, and self-esteem have been met that the drive for competence (i.e. growth, learning, development, mastery) can flourish. So personal reflection and my own knowledge gained through extensive study of human motivation, incentives, rewards, creativity, and complex tasks do not account for our love of competition. Readings Instead of reflection, maybe specifically hunting for an answer to these questions would be more fruitful. Maybe there are research articles, blogs, magazines, or books that can help me out. Not so much. While a Google search for “why is competition good” turns up 210,000,000 results, the first page contains mostly business and education articles with titles like 20 Proven Reasons Why Competition Is Good | Business Gross and Debate: Is Competition good for kids? - Ineos. A quick read through these articles shows very little critical thinking and almost no reference to any of the literature I hinted at above. For instance, the first article above has “proven” examples of how competition is good such as these gems: 2. Innovation Is Fostered That is the entire extent of the article’s explanation on these “proven” reasons. As you might guess from the reflection section, all of these can be done without competition. The other reasons fall into the same bucket. A quippy heading and one paragraph of explanation without any mention of evidence. Obviously, a general Google search and survey of the first page isn’t the best way to go about this. The same search on Google Scholar, which comprises research from academics in the form of journal articles and books, returns less enthusiasm on the benefit of competition. For example, one book on the link between competition and the common good returned the following, In The Darwin Economy, Robert Frank predicts that within the next century Charles Darwin will unseat Adam Smith as the intellectual founder of economics. The reason, Frank argues, is that Darwin’s understanding of competition describes economic reality far more accurately than Smith’s. Far from creating a perfect world, economic competition often leads to “arms races,” encouraging behaviors that not only cause enormous harm to the group but also provide no lasting advantages for individuals, since any gains tend to be relative and mutually offsetting. The good news is that we have the ability to tame the Darwin economy. The best solution is not to prohibit harmful behaviors but to tax them. By doing so, we could make the economic pie larger, eliminate government debt, and provide better public services, all without requiring painful sacrifices from anyone. That’s a bold claim, Frank concedes, but it follows directly from logic and evidence that most people already accept. A journal article on the link between competition and innovation returned this, The relation between the intensity of competition and R&D investment has received a lot of attention, both in the theoretical and in the empirical literature. Nevertheless, no consensus on the sign of the effect of competition on innovation has emerged. This survey of the literature identifies sources of confusion in the theoretical debate. So I am unconvinced by anything I am currently reading or finding. That search will continue until I’m fully satisfied, but I don’t foresee any plausible evidence turning up at this point.

Goal Attainment All of this brings us up to goal attainment and the connection that is becoming more and more clear to me as I search for answers to these questions. If you read up on the human condition and research on overall well-being among humans, a pattern will emerge that paints us as goal-seeking entities. Our brains and bodies are basically set up to allow us to satisfy desires and goals through our actions. Alfie Kohn in his book No Contest, an extensive review of competition and its lack of benefits, settles on defining competition as “mutually exclusive goal attainment”. This is important to understand relative to the other two options, which are independent goal attainment and cooperative goal attainment in which one is dependent on others to attain a goal. This definition means that if I attain a goal, another individual is not capable of attaining that same goal. Most sport competitions are set up in this manner. If I win a tennis match, then my competitor is, by the nature of the event, not capable of also winning the match. Our goals are mutually exclusive. What I take away from this connection is a dramatic reevaluation of goals. This separation of various ways in which to achieve goals does not tell us which goals are valuable or worthwhile. We can achieve goals in a mutually exclusive manner, an independent manner, or dependent manner (cooperation), but this doesn’t tell us whether those goals should be pursued. But recognizing these different ways of goal attainment immediately begs the question, “Why pursue competitive goals?” If they are mutually exclusive, why not simply choose goals that can be achieved independently or through cooperation? Many will often fall back and rely on the simple answer, “Competition makes us better. It brings out our best.” This is both an uncritical answer and at the same time shows a shallow and superficial way of thinking about these questions. Makes us better how, exactly? If we are talking about athleticism, which is probably the first thought related to betterment through competition, then we can point out that we can all be more athletic (better) without resorting to mutually exclusive goals. If I want run faster, that does not preclude your doing so. If I want to be stronger and lift more weight, that does not preclude your doing so. Those are independent goals, not competitive goals. If we are talking about intellect and knowledge acquisition in an educational setting, which is probably the second thought that springs to mind with relation to betterment through competition, we run into the same problem. My becoming smarter, more knowledgeable, or more creative does not prevent you from becoming so either. What is mutually exclusive is any kind of ranking system of who is smartest or who is most knowledgeable. We can set up an education system (we have such a one currently) that decides who is “best” in class through testing and then rank students from one to “n” in order to screen them. My being first in class is then mutually exclusive of your being first in class. This is a different goal than gaining more knowledge or skill, though, and it is very important to recognize that difference. Worthwhile Goals So what goals are worth attaining? What does this all point to? If you read my writing with any regularity you can probably guess. Goals that benefit yourself and others while not harming anyone intentionally or with any foreseeableness, at least not in a major way, are most worthwhile. Some of these goals might include hedonistic pleasure, novel experiences, deep connections to others, creative contributions to society through work and the pursuit of mastery, searching for personal meaning and life purpose, flow-state experiences, and a sense of contentedness and life satisfaction. None of these require competition. All of these can be attained through independent or cooperative means. Examine your goals carefully. Reevaluate if necessary. I’d like to end with one very clear point on worthwhile goals. Almost all of the truly world changing goals and many “everyday” altruistic goals aimed at bettering others’ lives will necessitate cooperation, not competitive or independent work. As a very simple example, let’s take my own writing, which largely aims to teach and share knowledge that I feel is valuable to making the world better by increasing everyone’s well-being. For many, many years, I have written independently. However, as I mature and relinquish this sense self-sufficiency in my writing and work, I am able to realize that writing an article is different goal from writing the best article possible to help the most number of people. In order to do that, I need to cooperate with others. I simply cannot write the best article possible alone. I depend on the help of others in the form of editing, revisions, encouragements and injections of ideas and perspectives new and different from my own that often illuminate obvious counterpoints or objections to my thoughts. By cooperating, the most obvious holes and gaps are plugged and any thesis I maintain is made stronger. This same point about the benefits of cooperation over competition holds true for any worthwhile goal I can think of, which is the central point of this article. In Matt Ridley’s words, “Self-sufficiency is another word for poverty”. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed