|

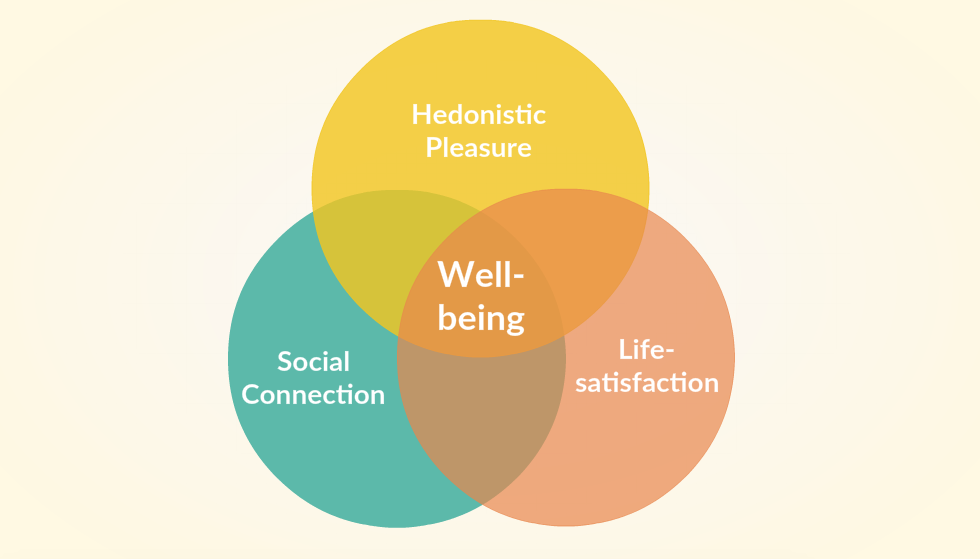

I realize I discuss well-being a lot in my writing, and it is one of my central interests, so it’s probably best that I explain where my ideas on the topic come from. Because it is a huge topic and one that I’ve spent so much time thinking and reading about, there is no way that I will be able to cover and include everything here. I am only attempting to capture a bit of the history of my thought on the matter and where I currently stand. With that in mind, let’s get started. Personal History I first read about the topic in Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics in high school in which he settles on eudaimonia as “the good life”. This more or less entails reflective contemplation and the development of virtues, characteristics such as moderation and temperance in all things. This also known as “the golden mean”. This work and much of his other writings (see Politics) have been classified as what modern ethicists describe as “virtue ethics”. It is a system, as the name implies, that believes in developing virtues as the path to well-being. I then picked up an anthology of western philosophy, which I unfortunately cannot remember the title of, but was very similar in nature and scope to this textbook, Classics of Western Philosophy. It traced the development of ideas and philosophic concepts from the ancient Greeks up to 20th century thinkers. This was the first place that I read about Epicurus, Aurelius, Descartes, Spinoza, Hume, Kant, Schopenhauer, Mill, Nietzsche, James, and Russell. Nietzsche was the one that stood out and I began reading the majority of his works, along with the major works of Epicurus, Aurelius, Seneca, Cicero, Spinoza, Schopenhauer, Mill, many of Russell’s, Lakoff, and Noddings. In addition to the primarily philosophical texts above, I read a number of Western and Eastern works that were primarily religious in nature. Those included Tao Te Ching, The Bhagavad Gita, The Kingdom of God Is Within You, The Analects, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, The Reason for God, The Imitation of Christ, The Joy of Living, and Islam and the Future of Tolerance. These exposed me to the deontological ethical systems, or “duty ethics”, from Kant and utilitarianism from Bentham and Mill. Nietzsche argued that modern man would have to “overcome” his previous ethical systems in a complete “revaluation of values”, something I still largely agree with. Lakoff’s text above does a fantastic job of comparing philosophies throughout time and grounding ethics within an embodied system without resorting to anything metaphysical. In college, I also stumbled upon the book Destructive Emotions, which is a dialogue between cognitive scientist Daniel Goleman, author of Emotional Intelligence, a gift my aunt gave me while still in high school, and the Dalai Lama, spiritual leader and former head of state of Tibet. Both of these books predisposed me to reading The Art of Happiness, yet another work coauthored by the Dalai Lama and a western doctor, this time a psychiatrist instead of cognitive psychologist. The Art of Happiness became a turning point because it was able to shift my mindset from that of complete relativism, to providing a foundation for morality in happiness. The basic premise is that we all seek happiness and wish to avoid suffering. By describing both the psychological phenomena examined in Buddhism and the brain science examined within neuroscience and psychiatry, the book made a huge impression on me. It persuaded through both subjective and objective evidence, something I often aim for in my own teaching and writing. From here, I dove into the ever growing research in positive psychology. I began primarily with the wonderful textbook A Primer in Positive Psychology. I then quickly moved onto more specific aspects of positive psychology like flow, exercise and the brain, aging well, making decisions, stress, relaxation, motivation, rewards and incentives, mindset, creativity, meaning, mastery and expertise, humanism, optimism, self-actualization, the effects of our subconscious and free will, attention and energy management, intelligence, thinking, self-renewal, emotion, marriage, and learning. All of this happened over a two year period while I was also completing a master’s degree in education focused primarily on how we learn, largely by investigating both language, literacy, and culture. Upon completing the degree, I moved to Dubai and then Singapore where my next bout of reading began. A friend in Dubai introduced me to the work of Sam Harris whose book The Moral Landscape had a huge impact. It discussed, similarly to the Dalai Lama and Goleman, that morality’s foundation should be the study of well-being and suffering, and that it is possible to treat that study scientifically in much the same way we study physical health. Seeing as I was already familiar with positive psychology treating happiness in this way, the study of morality in this manner made perfect sense. After the move to Singapore, I stumbled onto the work of Peter Singer and his book The Life You Can Save. This, too, was responsible for a large shift my thinking. I had already studied the works of Aristotle and the Greeks who discussed philanthropy, or the love and service of humanity, at length. I had also been exposed to the idea from Buddhism of the boddhisatva, an enlightened buddha who chooses not to go to nirvana, but instead stays in our reality to help others reach enlightenment. So too with Maslow and his later work on self-transcendence who “proposed that people who have reached self-actualization will sometimes experience a state he referred to as ‘transcendence,’ or ‘peak experience,’ in which they become aware of not only their own fullest potential, but the fullest potential of human beings at large”. Even with all of this exposure to helping others, on top of positive psychology’s largest single finding “that others matter” for our happiness, I never felt a sense of agency in being able to affect change among those suffering and only sought to affect my own happiness. I largely blame my undergraduate degree in economics for this outlook because of its focus on development work being rather unpredictable and often causing more harm than not. Sure, we could try to help, but we have 50/50 odds of just making it worse. Better to focus on the self. Peter Singer’s work has convinced me otherwise. Millions of people die from preventable diseases and poverty every year. To not attempt to help is morally culpable. Obviously, without accepting the evidence from positive psychology and Harris’ The Moral Landscape basing morality on well-being and suffering, this argument falls apart. However, both are grounded in empirical research and as Harris points out, if we can’t agree that certain states of being are worse than others, then we really have no point of agreement for even having a dialogue. Being in a state of depravity is clearly worse than not being in a state of depravity and we should do our best whenever possible to help alleviate that suffering in ourselves and others. What’s more, the majority of the research I’ve pointed to above demonstrates that helping others will make ourselves even happier. As the protagonist from Into the Wild states, “Happiness is only real when shared.” Turns out that all psychology, neuroscience, and economic research says this is true. The Algorithm SWB = f(HP, LS, SC) Subjective well-being is a function of hedonistic pleasure, life-satisfaction, and social connectedness. OWB = f(H, W, E, S) Objective well-being is a function of health, wealth, education, and security. Quality of life is a function of subjective well-being and objective well-being.

Subjective Well-being The subjective well-being function is what I want to focus on. The objective well-being function is certainly important, but I feel more intuitive. People are often able to look at a person’s life and tell you whether they are objectively well off. This is often a product of the political and economic situation in which the person lives, but also socio-cultural circumstances. I personally have found the capabilities approach to economics and human rights the most useful to draw on with regard to objective well-being. Indices like the UN’s Human Development Index and the newly created Social Progress Index do a decent job of capturing much of these objective qualities, with the obvious caveat that they could also improve or become more comprehensive. So while national, international, and supranational organizations have already done a decent job in measuring objective well-being, therefore making it redundant to cover here, there has been less consolidation of the findings within the area of subjective well-being among the various social sciences and humanities. In the function for subjective well-being above, I’ve included three central dimensions. These come almost verbatim from The Psychology of Desire, which states, “Finally, all might agree that happiness springs not from any single component but from the interplay of higher pleasures, positive appraisals of life meaning, and social connectedness, all combined and merged by interaction between the brain’s networks of pleasure and meaningfulness” (p. 129). The chapter containing the above quote looks at and examines hedonia specifically and is what is referred to by “higher pleasures”, which the authors contrast with Aristotle’s eudaimonia or “cognitive appraisals of meaning and life satisfaction” (p. 129). Finally, they add social connectedness based on research within the rest of the text. These aspects of subjective well-being fit within a much wider context of research on the topic. I feel they are capable of encapsulating the majority (all) of the other findings with the nascent field. Below I will explain just how this is so. Hedonistic Pleasure The first dimension is hedonism, which is concerned with life’s pleasures and pains. This goes all the way back to the ancient Greeks, where it was most carefully reflected on by Epicurus in his major work referenced above. For Epicurus, hedonism was largely concerned with eliminating the pain in life and not nearly as self-indulgent as modern day “epicureans” would have us believe with their concern for food and drink. Thankfully, we don’t have to go back that far as modern positive psychologists have found that positive emotions do in fact make us happier (no duh!). Even our dreaded materialism can, in fact, make us happier if we spend on and consume items which are congruent with our personalities or allow us to enhance our experiences, especially if they increase our relatedness to others discussed below. This aspect of well-being also includes the finding that novelty in our experiences and pleasures does make us happier. Beyond mere material and experiential consumption as sources of pleasure, this dimension would also include pleasurable states of being, such as good health, physical and psychological security, engagement in flow, and the ability to exercise autonomy, all of which have wide support within research as contributors to well-being. Life-satisfaction The second dimension is about taking a step back from the present feelings of happiness that you may experience day to day in order to get a wider perspective on life. Broadly speaking, does your life having meaning, purpose, and a sense of accomplishment congruent with your values? Do you have a sense of competence or even mastery? The category is largely about self-selected goal attainment, in contrast with the previous dimension’s focus on desire satiation (a subset of goal attainment). In exploring this variable, it’s best to begin with competence, which has one of the most robust findings as a basic human need among any of the items discussed here. Competence, along with autonomy and relatedness, can be found among many of the most prominent studies on what motivates human behavior. As we grow in competence, we often seek ever greater challenges through self-regulation based on our values, purpose, and meaning in life. By self-regulating, we are able to experience a sense of congruence regarding our personal beliefs and the goals we seek. This sense of congruence and actual achievement of our selected goals provide a deep sense of accomplishment. By iterating this process enough times, often with the help of deliberate practice and deep work, we are able to approach mastery, a deeply rewarding experience that often fills us with great pride. Social Connectedness Last, but most importantly, is our deepest human need to experience social connectedness. This is almost certainly the most important thread tracing through all of the research on subjective well-being. Connection to other humans is what allows us to most fully develop and grow as individuals and groups. In fact, modern neuroscience is beginning to show that morality is built on the foundations in our brain most closely connected to cooperation. Cooperation is the mode of goal attainment, in contrast to competition or independent striving, that most closely contributes to both of the previous dimensions above. By cooperating, we are able to satisfy our desires better and develop greater empathy for others, the basis of human connection and forming a strong concern for others (i.e. altruism). In learning to see others as subjects and not just objects to be overcome, we allow them to be more vulnerable and are able to accept their flaws, mistakes, and shortcomings, a process that many psychologists have found integral for human growth. Putting It All Together As I mentioned above, I will not be going into the components of objective well-being as they are more straightforward, have greater agreement, and therefore would be redundant. However, in looking at the algorithm above, what is important to realize is that it is the combination of both subjective and objective well-being that make up overall quality of life. Living standards can be objectively high and a person will still not experience a high quality of life if they are experiencing depression or other forms of subjectively low well-being. This is most evident in the alarmingly high number of suicide deaths in the developed world (America has suicide as the tenth highest cause of death in the country). Worldwide, a person is more likely to die from suicide than homicide or war combined. The most difficult aspect of this algorithm is finding the appropriate balance among the three components of subjective well-being. Oftentimes, our hedonism can stand in the way of our life-satisfaction and connection to others. Two short examples among an infinite number are when our short term desire satisfaction for sweets stands in the way of our chosen goal of being healthier, or when our hedonistic addiction to the pleasure of drugs destroys our connection to friends and family. This same issue exists for the other two dimensions as well. For instance, an obsessive focus on life-satisfaction within the narrow sense of goal attainment can lead us to avoid hedonistic pleasures and social connection through compulsive work, while an obsessive or dependent state of social connection can also detract from our enjoyment of self-centered pleasures and overall life-satisfaction by narrowing what it means to be fully happy and competent. What this boils down to is developing an ever larger sense of compassion and understanding for each other, which can allow us to accept people when they do make tradeoffs in the various dimensions, instead of jumping to judgement, which only creates division and alienation. If we recognize that we are all striving to be happy and fulfilled in life and that pursuit encompasses more than just the emotional feeling of positivity, the person that is aiming to enhance their well-being through a different dimension than you think best won’t be seen as wrong or bad. As long as we aren’t intentionally hurting one another, it should be accepted by all when a person chooses to increase their happiness through any of the three dimensions above. It is nearly impossible to eliminate suffering entirely, but we can alleviate it by cooperating and utilizing an “ethic of care” in our everyday lives. This propensity to enter relationships and address people with care as our first inclination can lead to a more connected and peaceful world, which will lead to a happier and better world.

3 Comments

Irma Fitzgibbons

9/15/2016 08:27:09 am

Great writing! Keep it up! I am proud of you.

Reply

Kyle Fitzgibbons

9/15/2016 08:44:57 am

Thanks Aunt Irma! I'll be home in December and early January for about three weeks. I would love to see you if you're in California! Love you lots.

Reply

Kyle Fitzgibbons

9/15/2016 08:45:32 am

Thanks Aunt Irma! I'll be home in December and early January for about three weeks. I would love to see you if you're in California! Love you lots.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed