|

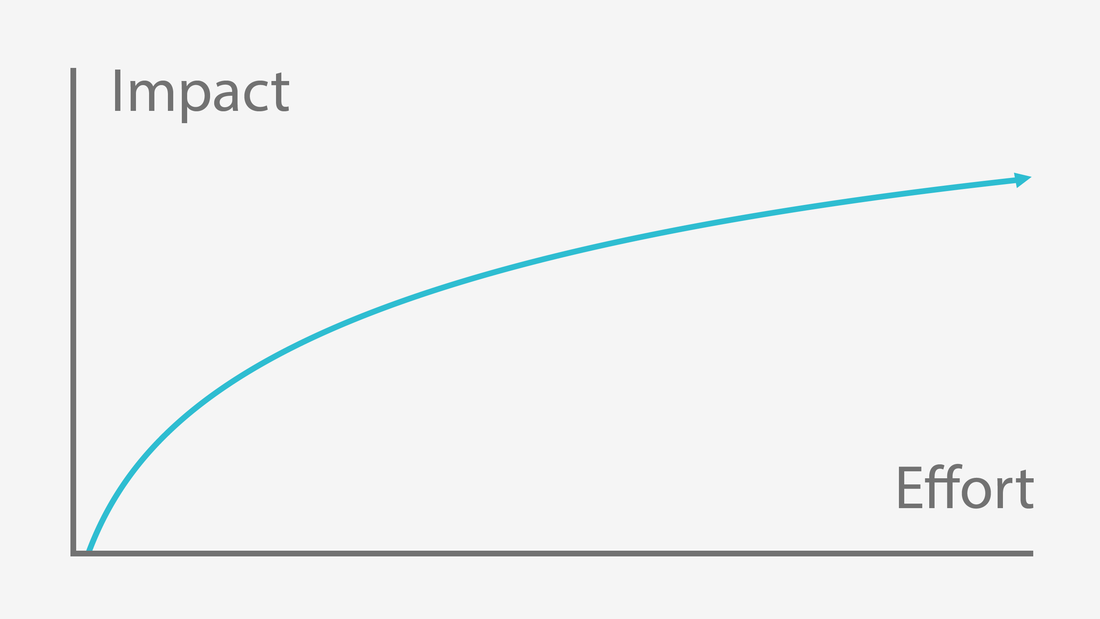

Rebecca, my co-author on Having Children: A Dialogue, recently published a blog with the following two paragraphs as an introduction. About three months ago, Kyle and I wrote and self-published a Kindle e-book called Having Children: A Dialogue. Since we find great value in freely sharing ideas, we also made the full text available on each of our blogs, which you can see here and here. The dialogue elicited a lot of discussion among our friends, both in person and on Facebook. I think she’s wrong. Here’s why. First, we need to be clear that I will be making a moral argument against adoption based on an ethic of care and the belief that good behavior is an attempt to maximize well-being for as many as possible. If you disagree with those two claims, you will disagree with many of my conclusions. Rebecca and I operate from the same ethical framework and so this rebuttal is on those grounds. In reading the initial draft of this response, Rebecca pointed out that it came across as self-righteous and when we look up the definition for that adjective we get, “believing that your ideas and behaviour are morally better than those of other people”. There will naturally be some truth to her impression because this entire discussion as I’ve framed it is a discussion on what ideas and behaviors are morally best. With that in mind, I will try not to be smug about it, which I think is closer to what her initial feeling of my tone was, and instead do my best to point out the conclusions that I think directly follow from the moral premises outlined above. Adoption Isn’t a Special Case It is the statement that adoption “needs to be talked about and celebrated” that I am reacting to here. Is this on the basis of its self-interestedness or its altruism? I assume the latter and so we have to ask just how effective it is as a form of altruism relative to the many choices we have and if it is less effective, what costs does that imply, and is the result still worth celebrating? When thinking about actions for impact regarding making the world better, adoption falls among the many options available and isn’t a special or unique one. We can still ask the question, “Will this maximize the good I am doing in the world or not, given the resources I have?” Of course, adopting is not always about doing the most good and we did touch on reasons for having children that fall outside that decision point in Having Children. However, once we move away from thinking about the most good we can do in terms of well-being and suffering, we are moving away from discussions on morality and into discussions about self-interested action. The organization 80,000 Hours does a great job on deciding how to find the world’s most pressing problems. They recommend using a three pronged approach that considers problems that are big in scale, neglected, and solvable. Adoption is definitely solvable, but does not count as big in scale (think human extinction due to climate change) or neglected (everyone knows of adoption as a viable choice to help others). This can be easier to see with the diagram 80,000 Hours included in the article linked above, copied immediately below for convenience: In the case of adoption, lots of effort and attention has already been paid to it, so it exists in the upper right part of the curve in the diagram above. In technical terms, it has low impact at the margin. As an additional person supporting adoption, your effort has far less impact than some type of action where you are starting at the bottom left corner of the curve near the origin where the impact at the margin is very high. This would be entirely different if adoption were a neglected cause. If everyone decided adoption was not effective enough in terms of impact per unit of effort, we would find adoption down in the left hand corner of the curve and a great example of “low hanging fruit” in terms of impact, i.e. something that is high impact because it is both solvable and neglected and therefore is easy to get high marginal benefit by undertaking it. That just doesn’t happen to be the case for adoption at this moment in time. Putting It More Humanely The major problem with talking about adoption in these terms is that it comes across as inhumane or out of touch with human empathy and compassion. Since that tends to be the case, it’s probably more effective to put it in a different perspective. If you had to make a choice between saving 50 to 117 lives or just one, what would you decide? I assume that most normally adjusted and moral people concerned with doing the most good would decide on the first route - saving 50 to 117 lives instead of one. That is roughly the decision I am making and arguing everyone should be making when thinking about adopting. The opportunity costs are simply too high for adoption. Let’s now analyze why this is true. According to the USDA who released an annual report in August 2014, below are the expenditures on children by families:

So the range of expenditures on a child in the United States is from $176,550 up to $407,820 depending on parental income. Obviously, these are averages and individual parent expenditures will vary. I assume a morally aware parent like Rebecca is likely to spend much less, but all else being equal, it’s a good place to start. The most cost effective charities in the world are currently able to save lives for roughly $3,500 each. If we divide the low range estimate of $176,500 by $3,500, we get 50 lives saved for the equivalent cost of raising one child to 18 years old in the United States. If we use the high end of the range estimated at $407,820 and divide by $3,500, we get 117 potential lives saved by opting not to adopt and instead donating to the most effective charities in the world. I realize the problems with these estimates, but there are two additional points to keep in mind. We are finding better, more effective causes each day, as research into effective giving is still in its infancy. This means the cost of saving an additional life is likely to come down. Furthermore, the costs of child raising do not include the costs of adoption, which are still relatively high and make the expenditure values for raising an adopted child even higher than the range estimated above. Those two factors combined result in even larger numbers of potential lives saved by choosing to donate over adopting, as the costs of children inflate due to adoption and the cost of saving lives comes down due to future learning. At the end of the day, this entire issue has much more to do with self-interested action versus altruism and moral “do-gooding” than it does with number crunching. If having a child makes your life complete, and adopting is your preferred method of doing that, by all means do it. If you adopting because you believe it is the best way to make the world better off, or even a fairly decent way to make the world better off, realize that is not really the case. There is a rather famous thought experiment within the field of moral philosophy known as the “trolley problem”: The general form of the problem is this: There is a runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person on the side track. You have two options: (1) Do nothing, and the trolley kills the five people on the main track. (2) Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person. Which is the most ethical choice? Adoption is currently a real life example of this thought experiment in action, except instead of saving five people and killing one person, your choice can potentially save over 100 people while not necessarily killing anyone (the potentially adopted child can still be adopted by someone else or live a less enjoyable life in state or foster care).

I don’t dislike adoption because I hate children or am apathetic to their suffering. It’s the exact opposite. I don’t like adoption because I see those 100 faces suffering and dying from preventable causes each time I picture it. Adoption is a decision that forces you to allocate resources to a single child for the life of that child. Ultimately those resources could have been spent elsewhere with greater impact and so adoption is equivalent to poor resource allocation when thought about morally. With all of this in mind, the decision to adopt should be thought about relative to your own interests and not as a decision regarding the greater good. After all, the greater good would urge you not to adopt at all, but instead use those resources to take action in higher impact areas.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed