|

I’ve always exercised for only a couple of reasons: to feel able enough to experience more of life and to avoid preventable diseases and injuries as I age. The latter reason is the primary impetus for me even when I feel unmotivated, but the former is a nice perk, almost a bonus as it were, and what has given me some of my best memories and feelings of accomplishments. Examples of the experiences I’ve had because of physical health include climbing Mount Whitney and Mount Baldy in California with some of my closest friends, squatting 402 pounds, deadlifting 500 pounds, running two half marathons, completing a triathlon, doing 20 pull ups at one time, spearfishing in Malibu, and otherwise enjoying outdoor leisure activities such as camping, hiking, bodysurfing, and various board sports. These memories and accomplishments due to physical health rival every other good memory I have outside this realm of physicality, including earning a Master’s degree, self-publishing Kindle and Audible books on Amazon, getting married, and helping students learn about and fundraise for valuable organizations. However, as I said above, it is really the prevention of diseases and injury that motivates me to maintain a minimum of physical health. Anyone who doesn’t know me that well won’t know this, but I’ve grown up with a father that has a genetic variation of emphysema. It is a disease that, as he has described it, “takes one new thing away from you each day, week, or year”. It’s progressive and miserable. He used to be able to lift heavy weights, run trails through the California hills and mountains, and play tennis vigorously as a serious hobby. Now, he is lucky to finish 18 holes of golf while using a cart and oxygen the entire time. Bending over to remove weeds in the garden can make him lightheaded and dizzy. Even showering, dressing, and putting on shoes and socks (bending over again) can be exhausting. With his ever looming physical presence in my house, I’ve been interested in warding off major surgeries and illnesses via prevention since I was a teenager. The 10 Leading Causes of Death Worldwide According to the World Health Organization approximately 56 million people die each year and the leading causes are as follows: Ischaemic heart disease, stroke, lower respiratory infections and chronic obstructive lung disease have remained the top major killers during the past decade. Leading Causes of Death in the USA According to the Center for Disease Control, the leading causes of death of the approximately 2.5 million annual deaths in America are:

To be even more specific, according to Harvard’s School of Public Health, approximately 2 million (of the 2.5 million total) deaths are preventable each year and are due to “dietary, lifestyle and metabolic risk factors”. The number of deaths annually due to these specifically preventable risk factors are:

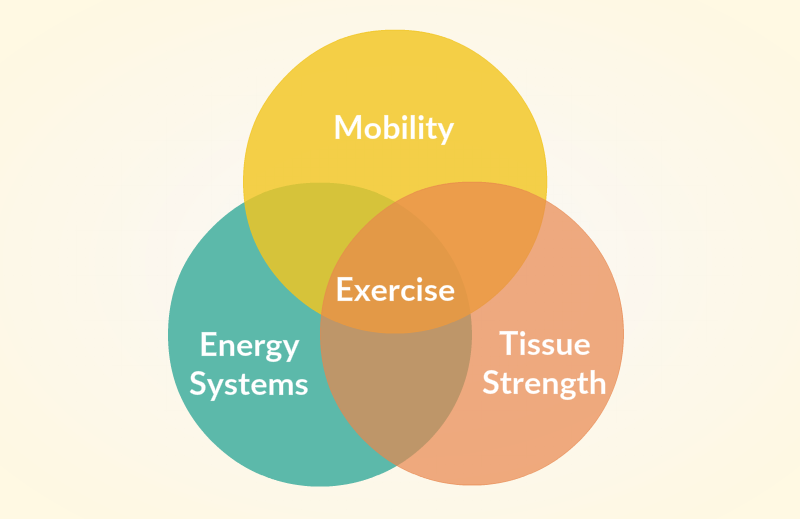

And to be even more specific still, according to the CDC again: Falls are the leading cause of injury-related morbidity and mortality among older adults, with more than one in three older adults falling each year, resulting in direct medical costs of nearly $30 billion. Some of the major consequences of falls among older adults are hip fractures, brain injuries, decline in functional abilities, and reductions in social and physical activities. Although the burden of falls among older adults is well-documented, research suggests that falls and fall injuries are also common among middle-aged adults. One risk factor for falling is poor neuromuscular function (i.e., gait speed and balance), which is common among persons with arthritis. In the United States, the prevalence of arthritis is highest among middle-aged adults (aged 45–64 years) (30.2%) and older adults (aged ≥65 years) (49.7%), and these populations account for 52% of U.S. adults. Moreover, arthritis is the most common cause of disability. (p. 379) What this all points to, if you live in the United States in particular, is a need to address long-run physical issues through prevention. Avoiding smoking, drinking, trans fatty acids, and high dietary salt and sugar aren’t that difficult. Neither are including poly-unsaturated fats, fruits, vegetables, omega-3 fatty acids, and exercise. Even though diet is clearly very important from reading the above, I find most people understand and know this. Rather, like flossing and other simple things involving willpower, they simply choose not to eat and drink well because of a host of reasons, sometimes individually based, but often social as well. What I find most people don’t do is make clearer connections to their exercise choices and the long-run prevention strategies that should become obvious as one looks over the data above. Exercise has a clear and robustly supported impact on some of the largest causes of death in the United States. Causes of death such as heart disease, respiratory disease, Alzheimer’s disease, intentional self-harm, high blood pressure, overweight-obesity, and the number one cause of death in old age, “falls”, are all directly connected to and can be decreased by our choices of exercise. So let’s examine what I believe to be the best overall approach to longevity given what the data above tell us. The Algorithm EfL = f(M, TS, ES) Exercise for longevity is a function of our mobility, tissue strength, and energy systems. Of course, overall health and well-being will include more than exercise. As mentioned above, diet will be one large aspect. Sleep would be another. Stress yet a fourth. And take a look at my algorithm for subjective well-being for variables regarding your mind, which also have a strong impact on your physical health. PH = f(D, S, E, St) Physical health is a function of diet, sleep, exercise, and overall stress levels. I won’t go into all the variables in the PH equation directly above, but will spend some time fleshing out the first equation on exercise for longevity. Mobility This dimension seems to be the most confusing to people. As physical therapist Charlie Weingroff puts it: Being fully mobile simply means the ability of a joint system to move through a definable range. This definition is great because it puts mobility into perspective. Mobility’s job is to let you do the tasks you wish to do. Nothing more. Being able to do a full splits may demonstrate extreme mobility of your hips, but if it doesn’t let you perform any other tasks that you deem important, then it is probably a bit silly to spend an inordinate amount of time gaining that ability. Gray Cook, another physical therapist, states it nicely when he urges us to “manage our minimums”. Our lack of mobility often gets us in trouble when it is asymmetric more so than when it is somewhat limited. What all this means is that you don’t have to take up yoga to become more “flexible”, i.e. mobile. You don’t win points for being more mobile than someone else unless that person can’t live a normal, independent life because of their poor ranges of movement. In general, once you decide that you do need to improve your mobility, physical therapy work will be the most effective practice, much more so than simply stretching. “You need a trigger point technique, a soft tissue technique, and a joint technique.” A good place to start for self maintenance is on physical therapist Kelly Starrett’s Mobility WOD. If you really do have mobility issues, this will get you much further than yoga or static stretching in much less time and energy. But again, mobility is relative to what you want to do with yourself. With longevity in mind, you are mostly worried about being able to get up and down off the floor and up and down off the toilet, along with reaching upward or downward to grab or pick up things. Those are really the biggest demands on most people’s mobility as they age. Anything past that will be mostly individual wants and needs. What improved mobility won’t do is prevent any of the major causes of death described above except perhaps “falls”, but this is more often related to muscle weakness and atrophy and is better addressed in the next dimension of exercise - tissue strength. Tissue Strength Human tissues come in two forms: soft and hard. Soft is easier to describe as saying it is everything that isn’t hard tissue, i.e. bone and tooth. That means that soft tissue comprises tendons, ligaments, muscles, fascia, nerves, blood vessels, skin, and a few others. In strengthening both hard and soft tissue, one can alleviate the chances of several of the risks above, including accidents, diabetes, high blood pressure, overweight-obesity, and inadequate physical activity. The best way to strengthen your bodily tissues is to exert stress on them through external weight. This means weight training, strength training, bodybuilding, Crossfit, or whatever other form of training you wish that involves weights of moderate load (60-85% of maximum), for moderate repetitions (5-20), and moderate sets (3-10). This is because weight training is the most effective way to increase bone density, tendon/ligament strength, muscle size, and regulate blood pressure, hormones, and hypertension. Basically, “Barbell training is big medicine.” The three best understood methods for maintaining muscle size and strength according to Brad Schoenfeld, PhD in exercise science, are through mechanical tension, muscle damage, and metabolic stress. Mechanical tension is created on a muscle, bone, tendon, or ligament any time we use a relatively heavy load. This is generally understood to be 60-100% of our maximal effort. Muscle damage is best elicited through exercises that have not been done recently, by providing a greater than normal stretch or lengthening of a muscle, and the use of heavy or slow eccentrics (lowering of a weight). Lastly, metabolic stress is the buildup of metabolites in a muscle and is best described as the “burn” we feel in our muscles from repeated contractions with little rest. Basically anything that Arnold Schwarzenegger would have described as a “pump” back in the 70’s is likely to induce metabolic stress in a muscle. A host of interrelated reasons explain why increased tissue strength and size are so effective at combating the above risk factors. Accidents are far less likely when we have strong bones and muscles that we have learned to coordinate through the coordination of our own bodies and external weights. Diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity have nearly zero chance of occurring with frequent weight training because more muscle means a higher rate of metabolism, as our tissues are where metabolism occurs. The repeated spiking of blood pressure during weight training actually works as a stressor that keeps our blood pressure lower when not exercising, just like raising our heart rate during running keeps our heart rate lower when not running. This type of exercise also has a large and positive impact on our hormones, causing several to be released and regulated in a healthy manner. Jonathon Sullivan, MD and PhD in physiology, summarizes all of these effects from strength training on longevity perfectly: And before you ask: at present there is absolutely no solid evidence that strength training—or any other exercise or dietary program—will substantially prolong our life spans. But the preponderance of the scientific evidence, flawed as it is, strongly indicates that we can change the trajectory of decline. We can recover functional years that would otherwise have been lost. There is much talk in the aging studies community about “compression of morbidity,” a shortening of the dysfunctional phase of the death process. Instead of slowly getting weaker and sicker and circling the drain in a protracted, painful descent that can take hellish years or even decades, we can squeeze our dying into a tiny sliver of our life cycle. Instead of slowly dwindling into an atrophic puddle of sick fat, our death can be like a failed last rep at the end of a final set of heavy squats. We can remain strong and vital well into our last years, before succumbing rapidly to whatever kills us. Strong to the end. Energy Systems Finally we come to energy systems training, which can help prevent the major causes of death, including heart disease, respiratory disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and suicide due to depression. We actually have three overlapping energy systems. These include the phosphagen system, anaerobic system, and aerobic system. The first two are used for short-term, high-intensity outputs like jumping, sprinting, weight lifting, etc. You can typically sustain the phosphagen system for up to 10 seconds and the anaerobic system for a couple of minutes (think 800 meter run) before you start to feel your lungs and muscles scream and burn. Both of these are easily addressed with whatever weight lifting you do for strengthening your tissues, but interval training can also do the trick. The third system, aerobic energy, uses oxygen and is what most people think of when they think of “cardio”. Anyone swimming, biking, jogging, or otherwise covering a lot of ground over a long time will be using this energy system. However, people today seem to have gone to extremes with ultramarathons, Ironman triathlons, and century bike rides. Andrew Hallam, summarizes the research well when it comes to cardio: Earlier this year, five researchers published a study in the Journal Of The American College of Cardiology. They found that, on average, joggers live about 6 years longer than couch potatoes. But those who run too far, too fast, or too frequently die earlier. They live about as long as a typical T.V. loafer. Putting It All Together

While all of this seems rather complicated, it’s actually quite simple. To do our most to prevent long-term health problems due to illness, injury, and death when it comes to exercise, we essentially want to physically train much like a bodybuilder. This means:

This will keep our tissues strong and healthy, our cardiovascular system in optimal condition, and our joints and movement patterns capable of the ranges of movement we need so we don’t succumb to dying by “fall” once we get over the age of 65. If we are living up to and beyond our 70’s and 80’s, we must plan accordingly. I’ve seen my dad suffer from pretty much all of the major risks above, including heart disease, lung disease, overweight-obesity, accidents, depression, and those are just the ones I know about. I do not wish to suffer the same as I age, especially as I don’t have any genetic reason why I would. None of this needs take any longer than traditional hour long classes at a local gym or the 10K you run 4 times a week either. Thirty minutes of weights, followed by 20-30 minutes of cardio, and zero to 10 minutes of mobility work will still only take an hour out of your day and can be done just two to four times a week like most recreational exercisers do anyway. Conclusion While the algorithm best suited for ensuring longevity from exercise is rather short and straight forward, it doesn’t take into account a host of other factors, some of which were touched upon earlier regarding diet, sleep, stress, smoking, drinking, and risky sex practices. In addition, it’s equally important to point out that on a day to day basis, driving is one of the most dangerous activities that we participate in and anything that you can do to reduce the miles driven on roads, the better. It’s also worth noting that accidents are the number one cause of death in the 25-44 age group and that suicide, homicide, and liver disease are numbers four, five and six. This implies that living in a country or city like Singapore, where a person typically drives less because of efficient public transport, has access to good psychological health services, is very unlikely to be a victim of homicide, and is forced to pay expensive cigarette and alcohol taxes, can actually be of great service in making it through a person’s midlife and into their later years unscathed by youth. I also realize that the most popular forms of exercise are not actually included in this algorithm. Yoga, running, biking, and swimming (ultra) long distances, Zumba, Pilates and the like really have almost no use outside of the psychological and social benefits they might provide you, which I think is what most people are actually searching for when they undertake these activities. They are similar in nature to the glass of wine people drink after work “for the health benefits”. The truth is they just make you feel better. The goal of this algorithm regarding exercise for longevity is ultimately to fill gaps in thinking for people. Many view running as a complete exercise program or something like yoga and Pilates as “all you need” for complete physical health. This is objectively not true. While both of these types of exercise give some narrowly received benefits, they completely miss the tissue strength enhancements that will be your biggest ally in in keeping independence and functioning in old age and do little to ward of the metabolic diseases of modernity. It isn’t that you can’t do the things you love and enjoy. It’s that by going about designing and thinking about exercise on the basis of what is objectively needed to prevent our leading causes of death and injury, we can also feel subjectively better. There are very few things as subjectively rewarding as being physically fit in all three of the dimensions described above: mobility, tissue strength, and energy systems. At the end of the day, there is no problem with doing things because they make you feel better psychologically, but it is important to separate facts from the delusions we often tell ourselves and realize that empirically and objectively arrived at choices for exercise can also be enjoyed subjectively while keeping you healthier in the long run. Even if it means learning and doing new things you initially find uncomfortable or possibly even painful, the payoff for both you and society is more than worth it.

1 Comment

|

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed