|

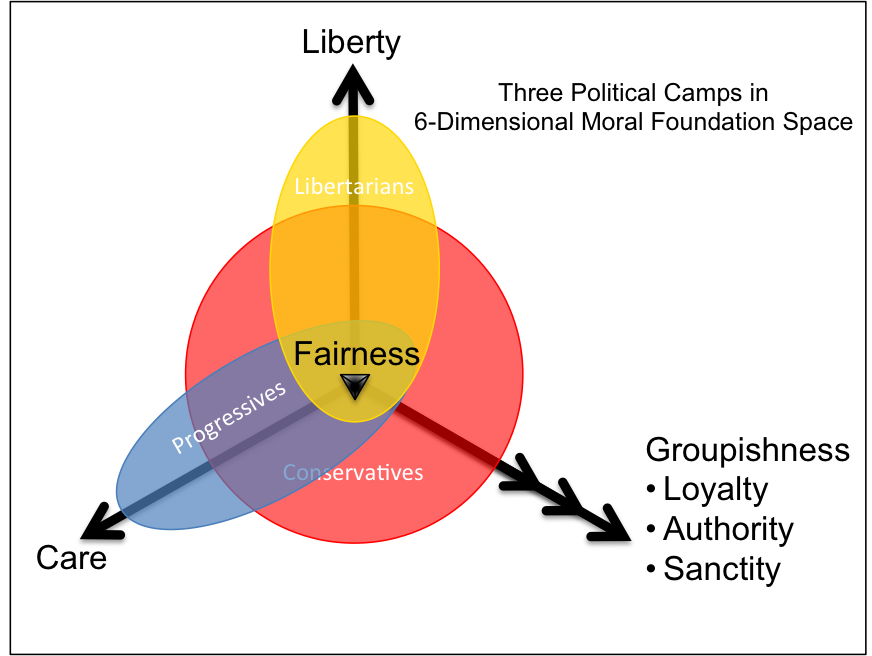

Humans as social animals have several modes of interaction and many models have been created in attempts to categorize them. Fiske describes communal sharing, authority ranking, equality matching, and market pricing as ways that humans relate to one another. Graeber writes about communism, hierarchy, and exchange. Using Graeber’s model allows us to collapse Fiske’s equality matching and market pricing as two different forms of exchange into one category. Haidt says we rely on universal values of care, fairness, liberty, authority, loyalty, and sanctity. His research shows that conservatives reliably use and weight all six values more evenly than progressive liberals, who rely primarily on care, fairness, and liberty, which he interprets as conservatives having a more complete set of moral “tastebuds”. Greene builds on Haidt’s research in conjunction with Kahneman’s research on thinking fast and slow, to point out that our intuitive “fast” thinking often deals with the more conservative values of loyalty, authority, and sanctity, while our “slow” rational thinking often moves us beyond them to the more liberal values of care, fairness, and liberty. This movement into the slower, rational thinking allows us to cooperate with not just our own tribe members (i.e. “us”), but members from other tribes (i.e. “them”) as well by tapping into more utilitarian cost-benefit analysis of what will benefit us over the long run.

Lakoff simplifies all of these categories even more by developing what he calls “frames”. There are two basic frames - strict parent and nurturing parent. These, according to his research, fundamentally divide conservatives and liberals respectively and allow us to understand how various “wedge issues” are developed by both sides. All of this research is useful for understanding how humans interact. However, when looked at as a whole, I see two large divides: people that rely on exchange based utilitarianism and people that rely on hierarchical based duty ethics. The two closest models to this are Graeber’s comprised of communism, hierarchy, and exchange and Lakoff’s strict and nurturing parent frames. I believe the utilitarian exchange model of social interaction is one with substantially more benefits, while the latter is baser and often relies on violence to enforce the duty bound hierarchy rules. Violence All of the above is necessary information to discuss violence more generally. Resorting to violence effectively resorts to hierarchy, with “might makes right” being the highest decision making rule at the top of the pyramid. When two parties come into conflict they can choose to exchange conversation or use violence to resolve it. Those are our two tools. With violence, the person with the most might is always “right” and the person with the least might is always “wrong”. This results in taxonomies of power, with rulers on the top and the most oppressed and vulnerable at the bottom. This is why “liberty” doesn’t sit well with hierarchy and we use the term “liberated” for oppressed peoples that become free of the “might makes right” rule of interaction inherent in hierarchy. The liberation is that of a person who is free of violence or its threat and capable of entering into exchange based modes of interactions. These include the majority of social interactions that have caused human progress: free speech, freedom to experiment, freedom of assembly, freedom to enter into contracts, freedom to negotiate, and freedom to persuade others through rhetoric of better ways to live. This liberty is not necessarily in direct contrast to communism as Graeber uses it. In his model, communism is the approach to interaction where a person acts out of desire to do so with no expectation of something in return. There is no initial conflict or disagreement as with exchange or hierarchy. Person A: “Can you pass me that water bottle?” Person B: “Sure, here you go.” This is communism in its purist form, “From each according to his ability, to each according to his need”. Person A “wants” the water bottle and Person B is able to provide it. What you don’t see is a response from the favor-doer asking the favor-asker what they will get in return, nor do you see the favor-asker forcing the favor-doer to do it as you would see in exchange and hierarchy respectively. Most familial interaction between parents and children is performed on the basis of communism. Parents do things for their children without the threat of force from the children or because they are hoping to exchange their services for ones provided by their children. It’s also how many strangers interact on the street when asked for directions or the time. We simply help because we are able to do so. It’s the bedrock of human interaction and the most prevalent in day-to-day life. The other two, hierarchy and exchange, are our options when we don’t want to help, interact, or do something that another is asking of us and they are the ones we must decide between when thinking about and discussing violence. Person A: “I think we should do X.” Person B: “I think we should do Y.” If we assume X and Y are mutually exclusive and have different outcomes, we must figure out a way to resolve this conflict. We can use hierarchy, which at its essence is a threat of violence or a resort to actual violence. “We will do X or I will hurt you. If you understand my threat is real, you can choose to acquiesce quietly or test my resolve and force me to actualize the threat into real violence.” Much of the world operates on this model to this day. See the wonderful book The Locust Effect for several hundred pages of current day examples of the billions of people living in poverty. However, we do not need to go into the world of poverty to see this effect. Any place where hierarchy exists, there is some threat, whether apparent, disguised, or hidden, of violence. Our schools are an excellent example of hierarchy backed by violence. Students are at the bottom, above them are teachers, then administrators, then superintendents, and somewhere higher up is the state. The state is commonly described as being the sole legitimate monopoly of force (violence). This means that students are ultimately compelled to act as they are told because of the threat of violence that exists from the state. Student: “I want to do X.” Teacher (State): “You must do Y or I (the state) will do A to you.” This is not communism or exchange. It is hierarchy and the threat of violence, thinly veiled. Exchange on the other hand is the heart of liberalism as embodied in democracy and capitalism when properly understood. Person A: “I want to do X because of reasons A, B, and C. All of the reasons A through C will benefit you greatly, even more than action Y that you want to do.” Person B: “I did want to do Y, but you have persuaded me with your sweet talk and rhetoric that X is better. Let’s do X.” This example is simplified and may even come across as silly, but is exactly what happens every time we interact and exchange with others. When we think of free-markets, the reason they are so beneficial is that no one forces you to purchase the products and services. We do so because we’ve been convinced to exchange our money (a store of value) for the benefits the goods and services provide. This exchange makes us better off overall. We have traded something of value (money) for something of benefit. Exchange doesn’t happen unless it is mutually beneficial, unlike enforced hierarchy that tends to benefit only one party at the expense of the other. Of course, some of these exchanges take place over much longer time periods and some require much more convincing. But remember, assuming a person doesn’t want to undertake the action of their own volition, we really only have two choices: discuss, dialog, persuade, convince, reason, sell, talk, OR revert to force. Liberalism and all the progress it has brought humanity is fundamentally premised on choosing the exchange option, on recognizing that persuasion is a more dignified and humane way of interacting in the world than using force. Liberalism doesn’t deny that force is sometimes necessary. The state has ushered in a great deal of security and the world is less violent now than ever before. However, it does make our choices clear - violence or persuasion. Seeing this clearly has many implications beyond the example of school used above. For exchange to work, people must become far more comfortable with the simple “live and let live” motto when they find themselves in disagreement. As a default mode of interaction, it requires people to lay violence aside as an option. Taking violence off the table makes it so people either spend the time convincing others they are right or walking away. No compulsion allowed. This makes people very uncomfortable and often quite hurt or angry when they don’t get their way. Self-righteous indignation is a common reaction for those who are unable to convince or resort to violence. That needs to be accepted and people should learn how to adapt to it. A person’s inability to cope with discomfort, a sense of being wounded, or anger is not a reason to resort to violence. When all people accept this, the world will be a much more peaceful place. Take this writing as my attempt at persuading you that the world of exchange is a better world.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed