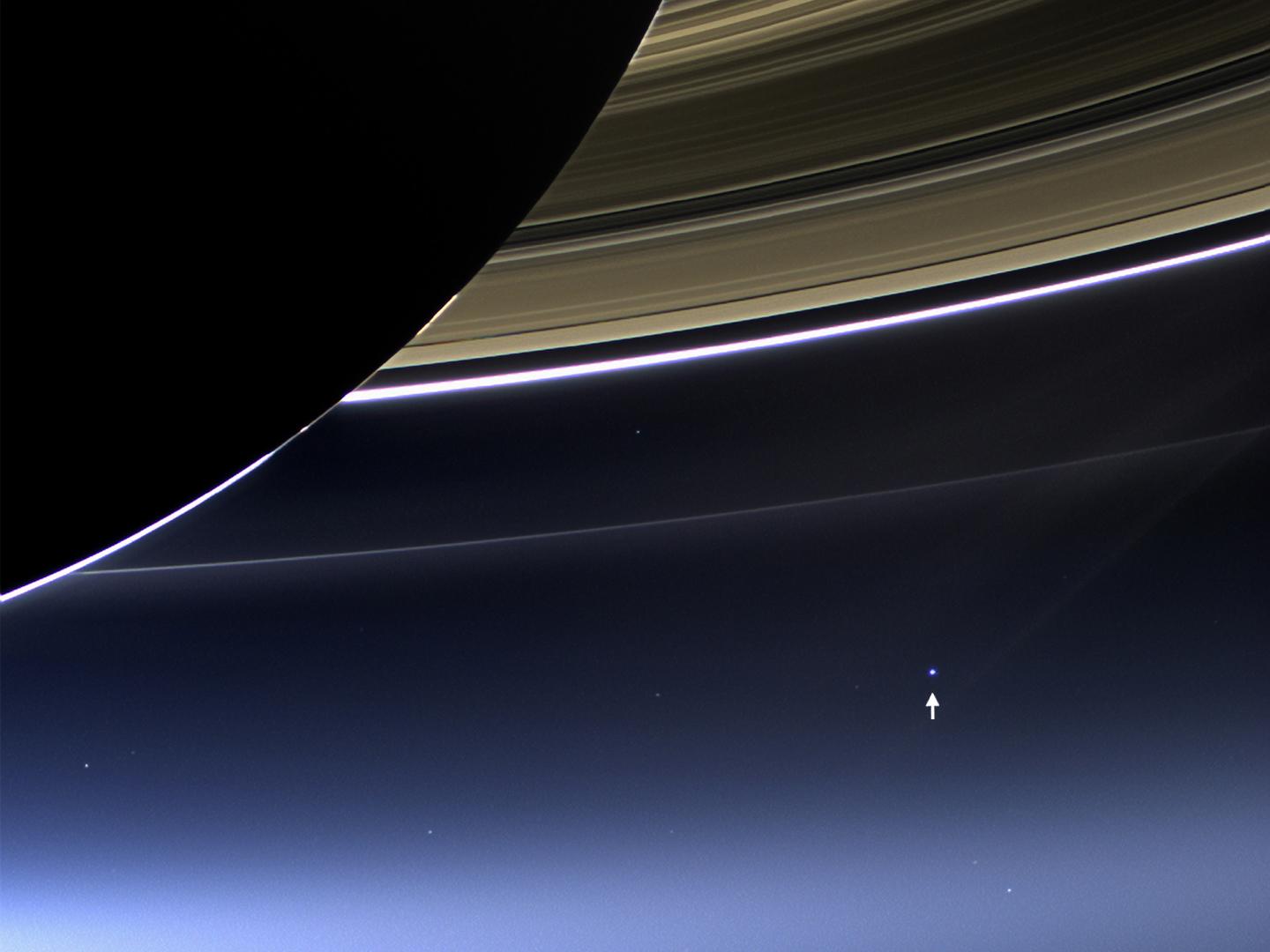

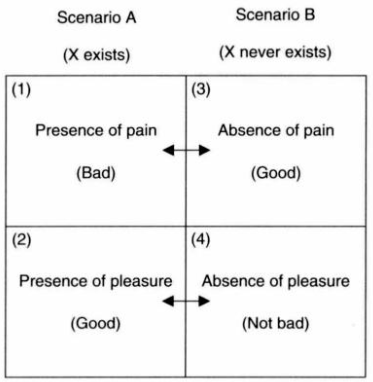

Q. What is Rejectionism? The above comes from Anti-Natalism by Ken Coates. It’s a wonderful little book written to explain the philosophical viewpoint of rejectionism by situating it in its historical religious, philosophical, and literary contexts. It’s also worth pointing out his second point completely overlaps with current understanding from modern physics and biochemistry. Life is just self-sustained replication with the help of added resources. In fact, Kurt Gray writes in Know This, The MIT physicist Jeremy England has suggested that life is merely an inevitable consequence of thermodynamics. He argues that living systems are the best way of dissipating energy from an external source: Bacteria, beetles, and humans are the most efficient way to use up sunlight. According to England, the process of entropy means that molecules that sit long enough under a heat lamp will eventually structure themselves to metabolize, move, and self-replicate— i.e., become alive. Granted, this process might take billions of years, but in this view living creatures are little different from other physical structures that move and replicate with the addition of energy, such as vortices in flowing water (driven by gravity) and sand dunes in the desert (driven by wind). England’s theory not only blurs the line between the living and the nonliving but also further undermines the specialness of humanity. It suggests that what humans are especially good at is nothing more than using up energy (something we seem to do with great gusto)— a kind of specialness that hardly lifts our hearts. (Kindle Locations 269-276) Back to rejectionism. Coates continues, Q. What are the core values of rejectionism? Christine Overall echos the above sentiments in her book Why Have Children?: The Ethical Debate when she writes, “The so-called burden of proof—or what I would call the burden of justification—should rest primarily on those who choose to have children,” (Kindle Locations 225-226). Overall goes on to clarify, The questions we should ask are whether such a desire [to procreate] is either immune to or incapable of analysis and why this desire, unlike virtually all others, should not be subject to ethical assessment. There are many urges apparently arising from our biological nature that we nonetheless should choose not to act upon or at least to be very careful about acting upon. Even if Aarssen is correct in postulating a “parenting drive,” such a drive would not be an adequate reason for the choice to have a child. Naturalness alone is not a justification for action, for it is still reasonable justification for action, for it is still reasonable to ask whether human beings should give in to their supposed “parenting drive” or resist it. Moreover, the alleged naturalness of the biological clock is belied by those growing numbers of women who apparently do not experience it or do not experience it strongly enough to act upon it. As Leta S. Hollingworth wisely noted almost a century ago, “There could be no better proof of the insufficiency of maternal instinct as a guaranty of population than the drastic laws which we have against birth control, abortion, infanticide, and infant desertion.” (Kindle Locations 241-249) This starting point is important. It already takes us far beyond the normal line of thinking which takes life for granted and gives no second thought to it. But what if life isn’t good? What if it shouldn’t be perpetuated? Naturally, this viewpoint can be jarring. It conflicts with our instincts and drives. That’s the whole reason it needs to be laid out carefully. It doesn’t “feel” right. That’s largely a byproduct of our evolved psychology and we shouldn’t let it mislead us. This is why Coates explicitly states, “It follows that to endorse existence is to condone evil, indeed to invite evil, albeit unintentionally. It follows that those who support and endorse existence are responsible, even if indirectly, for the crimes of humanity” (Kindle Locations 2020-2021). In this view, “acceptance” is an endorsement of evil and “rejection” is a compassionate act undertaken to avoid needless suffering. Given the above, the well-lived life entails rejecting existence as good, not procreating, and supporting philosophical anti-natalism. Because this worldview is so contrarian, the most good one could do in terms of alleviating suffering is to simply spread these ideas. In that sense, it is an optimistic worldview in that it does aim for a better world, although not quite the one most imagine. The vast majority of people will not agree and so a sea change of needs to occur. Some of the people I currently admire the most do not question existence at all and often state a tacit or explicit endorsement of “acceptance”. This troubles me because I respect them greatly, find them extremely intelligent, rational, curious, and scientifically oriented. If even these people endorse acceptance by default, it will be a very long road to a majority that endorses rejection. Of course, this philosophical worldview should be open to debate and I am open to change. It is my intense desire to change, however, that has only deepened this view. Listen for and ask people why existence is good. The answers are always completely unsatisfying. Some sort of endowment effect is typically to blame, even among the staunchest atheists and scientists. “Well we’re alive already, so we might as well give it meaning and purpose while extracting the most happiness out of life as possible.” I agree with that statement entirely, but it does not then follow that we should create more life. Given that we are alive, find some meaning and learn to enjoy while minimizing suffering. Don’t go out of your way to bring more life into existence though, because existence itself isn’t good. Making the most out of a bad doesn’t make it good, just less bad. Several reasons for this misstep in thinking are laid out by Benatar, including evolution selecting for optimism, self-deception as a coping mechanism, and the instincts of survival and reproduction that are reinforced via social norms and religions. If convincing people they are in fact wrong, or at least showing people there is an alternative way of thinking, is the most good one can do, then much of the fuss of global issues can somewhat melt away. One could spend their life supporting institutions like the Future of Humanity Institute, which support an acceptance worldview, or one could try to point out to those very sophisticated, intelligent, and rational folks why they are focused on the wrong problem. That would have huge marginal impact because almost no one is doing it. On the other hand, those very smart people may be able to turn around and convince me that progress is indeed possible and that a pessimistic view of humanity should not be undertaken in support of rejectionism. That is a tall order on their part, but one I would happily welcome. I would love nothing more than to be shown credible evidence that progress is in fact possible. The key progress would be that of moral progress, not material progress. It is obvious that we have had material progress. The last two hundred years have been incredible in that regard. However, people adapt to material progress rather quickly and life satisfaction seems to improve little. Furthermore, even in a world of complete abundance and no scarcity, does anyone honestly believe that suffering would cease to exist? Would we not continue right along with our endless violence, murder, rape, torture, maliciousness, and emotional abuse and victimhood? Tyler Cowen’s recent book, The Complacent Class, contained a remarkable passage quoted from 1177 B.C., which read, The economy of Greece is in shambles. Internal rebellions have engulfed Libya, Syria, and Egypt, with outsiders and foreign warriors fanning the flames. Turkey fears it will become involved, as does Israel. Jordan is crowded with refugees. Iran is bellicose and threatening, while Iraq is in turmoil. AD 2031? Yes. But it was also the situation in 1177 BC, more than three thousand years ago, when Bronze Age Mediterranean civilizations collapsed one after the other, changing forever the course and the future of the Western world. It was a pivotal moment in history— a turning point for the ancient world. (pp. 202-203) Humans seem, for evolutionary reasons, to be incapable of living without causing the pain and suffering of others. Perhaps moral progress is possible, but it clearly hasn’t happened much in the previous three thousand years. Do we need three thousand more or should we just conclude that the majority of humans will never be capable of the type of moral progress necessary? I would tend to believe the latter. This belief does not rest on Cowen’s passage only, but also on numerous examples. Neurobiology and the Development of Human Morality walks the reader through a host of problems with overcoming abnormal development in humans. Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman has shown us that we often feel the “bad” in life roughly twice as strongly as the “good”. Daniel Gilbert and Matthew Killingsworth have done work that shows “mind wandering” makes us unhappy and then went on to show that much of our mental activity (47%) throughout the day is mind wandering. We better hope no more than three percent of the rest of our day spent in active attention doesn’t make us unhappy or there is a very weak case to be made that the majority of life is spent happily. The best we might hope for if the majority of our time is spent in suffering is that the sea of unhappiness is swamped by a few high points here and there. Providing additional weight to increase the average in this way would only enhance the argument for utility monsters being okay though! I’m not sure most people are willing to do that, but I am not opposed to endorsing that view and it would be one view in support of a superintelligent AI replacing us. In any case, that does seem to be how our memory works at least. Benatar cites that, “when asked to recall events from throughout their lives, subjects in a number of studies listed a much greater number of positive than negative experiences” (Kindle Locations 674-676). Of course, Benatar’s main point isn’t that the good does swamp the bad, if only in recall, it’s that no swamping is possible in principle because of the asymmetry between existing and not existing, i.e. not suffering in non-existence is “good”, but not experiencing pleasure or happiness in non-existence is “not bad” when we need it to be “bad” for a symmetry to occur. Noting the above makes plain what would need to happen for existence to be considered okay. Either the presence of pain in existence must disappear entirely, or the absence of pleasure in not existing must be shown to be bad. Neither seems likely.

Whether moral progress in regards to suffering is possible seems to be of the utmost importance for accepting rejectionism. The only information I’m currently aware of that points in this direction somewhat is Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature. This tome provides hundreds of pages evidencing that we are currently living in the “safest” time period in history and that violence has declined. Many have disagreed with his research and presentation of it, but I don’t think even that is necessary to claim that his premise of decreased physical violence in no way means a decrease in suffering necessarily. I am happy to be living in such a safe time period. Truly. That doesn’t mean that the motive to cause suffering or the psychological capacity to experience undue suffering has decreased in any way (remember, we need zero!). We still react excessively poorly when we find a loved one has “cheated” on us. We still behave passive aggressively. We still eat meat and cage animals, although admittedly progress seems to be occurring on this front, but it could be my own perception as we absolutely have more caged animals now relative to any time period in history. We still have slavery. Psychopaths still exist. Sociopaths are not going away. So to say we no longer suffer from mutilation and torture in a public square (see the Middle East, however) is not to say much in reality. Existence is still rife with both physical and psychological pain. To summarize, existence is not good when compared to the alternative of non-existence and should be rejected. Moral progress seems, from all evidence, to be impossible for humans, despite increased safety and wealth. So how do we live? Well for starters, it is totally up to us whether we do or not. Ending our lives is a perfectly legitimate action, although of the egoist variety as it is done for the self. The altruistic action would be continue living and spreading the worldview of rejectionism. This could do more to alleviate suffering than any other single action. In terms of effective altruism and application of 80,000 Hours criteria of scale, neglectedness, and solvability, existence appears to be at the top of the list of problems for now.

1 Comment

Richard Wilkins

10/29/2023 07:30:09 am

I see that human beings have the ability to choose whether to have children or not. Depopulation is occurring in all industrial nations globally, mainly due to the cost of raising a child or children. Also, a growing number out of choice.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed