|

If you didn’t read my article on intelligence, please do so before reading this. It will make a lot more sense.

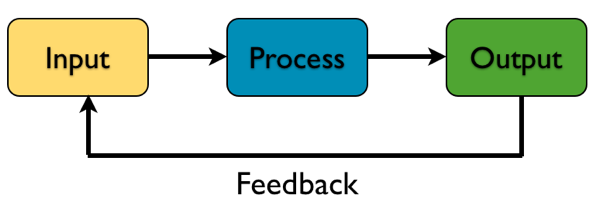

I tend to think about and relate most of what I read to education. The ideas of information, computation, learning, and intelligence are no different. I immediately began asking myself how my understandings framed my thinking about education. After some reflection, the impact is straightforward. Education is a function that is used for computation. We take inputs and produce outputs, which hopefully reflect our pre-selected goals. As we improve the function of education, we are learning to accomplish our goals better. Some questions that immediately spring to mind are, “What are we aiming to produce? What are our inputs? Is there or should there be only one function of education?” I think the answers will be different for different groups of people, but believe the method will be similar across the board. For example, I work at a large, private, international school in a wealthy, highly developed nation. If I were planning the vision, mission, and overall strategy of the school, I’d collect as much information about what the customers of the school wanted in terms of output for their money. Are they paying for a nice facility, like a day spa for their children? Are they paying for their children to be happy? To network socially for future employment and investment opportunities or simply to learn academic skills and knowledge? Do they want specific access to universities or just well paying jobs, regardless of college education? Is it important that their children become altruistic adult citizens? It would be possible to receive data on all of these answers and also to have the parents go further in weighting them by assigning percentages from a total of 100. For instance, they may be hoping that roughly 30% of their spending is going to simply producing happy children, 20% for access to networks of various types, 25% to beautiful and up-to-date facilities, and 25% to academic skills and knowledge. This would give a clear idea about the outputs or products of the school’s function the parents are hoping for and then it’s a matter of improving the computation of the inputs (students, resources, curriculum, etc.) to those outputs over time. That would be the definition of a “learning school” and could be checked yearly from surveys to parents about how well these weightings are being met over time. If parents report via surveys after the first year that they believe the school is actually devoting 80% of school time to academic skills and knowledge, instead of the hypothetical 25% above, the school would know they have to drastically shift their emphasis in the next year. They have seriously neglected the production of happy children, social networks, and aesthetic facilities. Naturally, it might take some time in operationalizing these metrics and getting information with high validity, but that is part of the learning process that improves the function over time. This does two things, it makes the literal function of the school exceedingly clear and makes it much easier to measure success. A byproduct of this approach is that it could very well mean de-emphasizing academics quite heavily. If parents mostly care about the happiness of their children, for example a weight of over 50%, then the school would feel liberated to focus much less on particular subjects and academic metrics like grades and instead to direct many more resources into programs that foster aspects of positive psychology, like positive emotions, engagement, relationships with others, meaning, and accomplishment. On the other hand, it would also make it easier to focus nearly 100% of resources to academics if the parents are clearly communicating that that is what they want. This would liberate the school from wasting time and energy on programs related to sports or the arts. Furthermore, the school may have heterogeneous groups in the community that each expect different functions of the school. This would make it easier to clearly offer multiple pathways for the inputs of students to the outputs desired. This last point would seem to imply larger schools, as Asbury and Plomin recommend in their wonderful book G Is for Genes, due to the advantage of economies of scale when it comes to running multiple programs, pathways, and options. Smaller schools would simply have too difficult a time offering multiple functions of school for parents to choose from. An alternative would simply be smaller schools with single, specialized functions. Is any of this revolutionary? I don’t think so. However, it is much clearer than most people I’ve read or listened to in education communicate. If we want specific goals to be achieved, we have to act intelligently. This means improving the computation of inputs into outputs over time, i.e. learning. That entails clearly describing what outcomes or goal states we want to achieve, which may be multidimensional and require weightings of different priorities, so that we can assign our inputs wisely in the transformation processing. Will everyone agree on what the goal should be? Of course not. I’ve written about what I think education’s goal should be, described what it might look like, offered a possible syllabus of books to help create it, and also written more generally why I think good teachers don’t exist. Whether or not good teachers and schools exist objectively, intelligent ones certainly do and using the above language in precise ways can help us communicate more clearly and elevate all of our intelligences for whichever goals we aim at.

1 Comment

5/2/2018 02:14:07 pm

It's always been a topic whenever there is a debate about education. Do schools have big impact to students who will succeed and those who will not? I always believe that our education and the knowledge we can gain are not after where we graduated. It will always depend on our capacity and determination to succeed. If you want to achieve something in life, you must work hard for it no matter where you came from! Dedication is something that's not being taught in school that we should learn.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2017

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed